by r Hampton | Feb 12, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – The Status of State Personal Exemptions a Year After Federal Tax Reform

Key Findings

- Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the personal exemption is suspended through 2025, balanced by other provisions, including the near-doubling of the standard deduction and an enhanced child tax credit.

- Some states mirror the federal government’s personal exemption, but many others set their own dollar amounts while using federal eligibility definitions.

- Conformity to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act introduced doubts about the status of some states’ personal exemptions, with the federal approach—zeroing out the personal exemption rather than repealing it outright—interacting with state statutes in unexpected ways.

- Six states saw the repeal of their personal exemptions under TCJA conformity, while legislators in another five states acted to preserve exemptions that might otherwise have been wiped out.

- Minnesota would lose its personal exemption if the state updated its conformity statute without expressly providing for its retention, and ambiguous language remains on the books in several other states.

Introduction

When federal lawmakers suspended the personal exemption for tax years between 2018 and 2025, that decision had ripple effects in the states, many of which incorporated the provision into their own tax codes. Whereas most other individual income tax changes under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) proved fairly straightforward for states to incorporate, zeroing out the personal exemption created significant uncertainty in some states and, for a few, took much of the year to sort out.

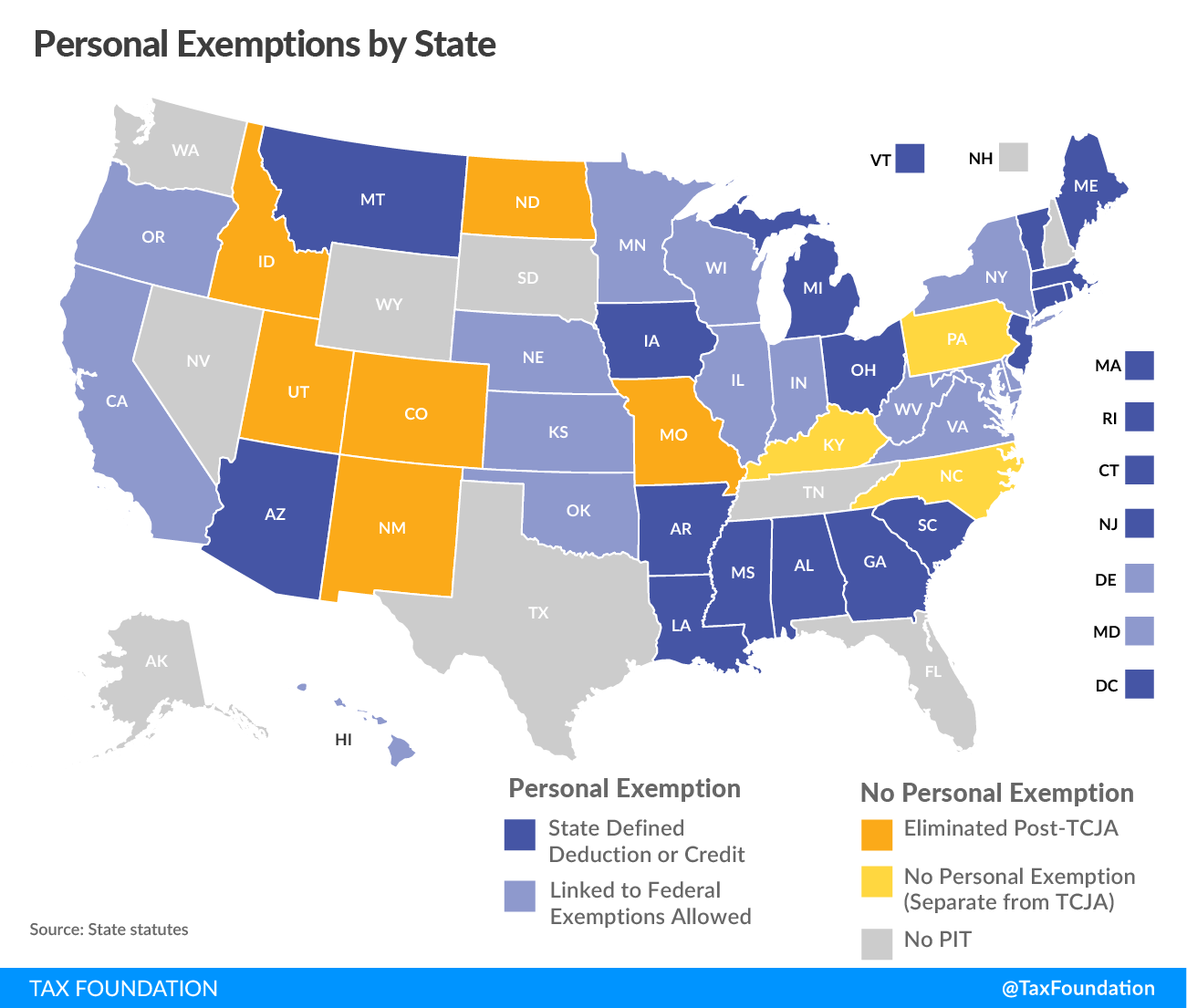

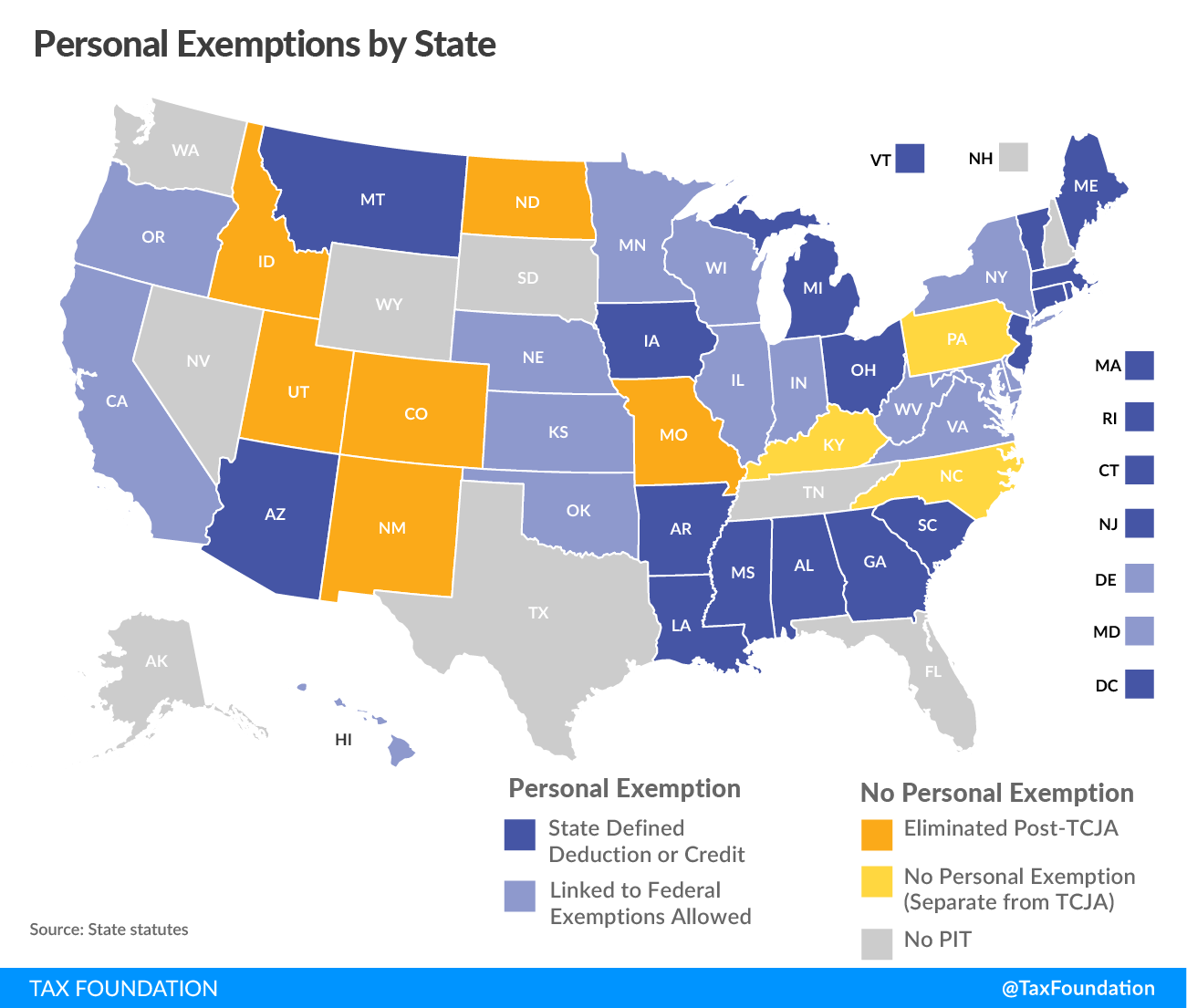

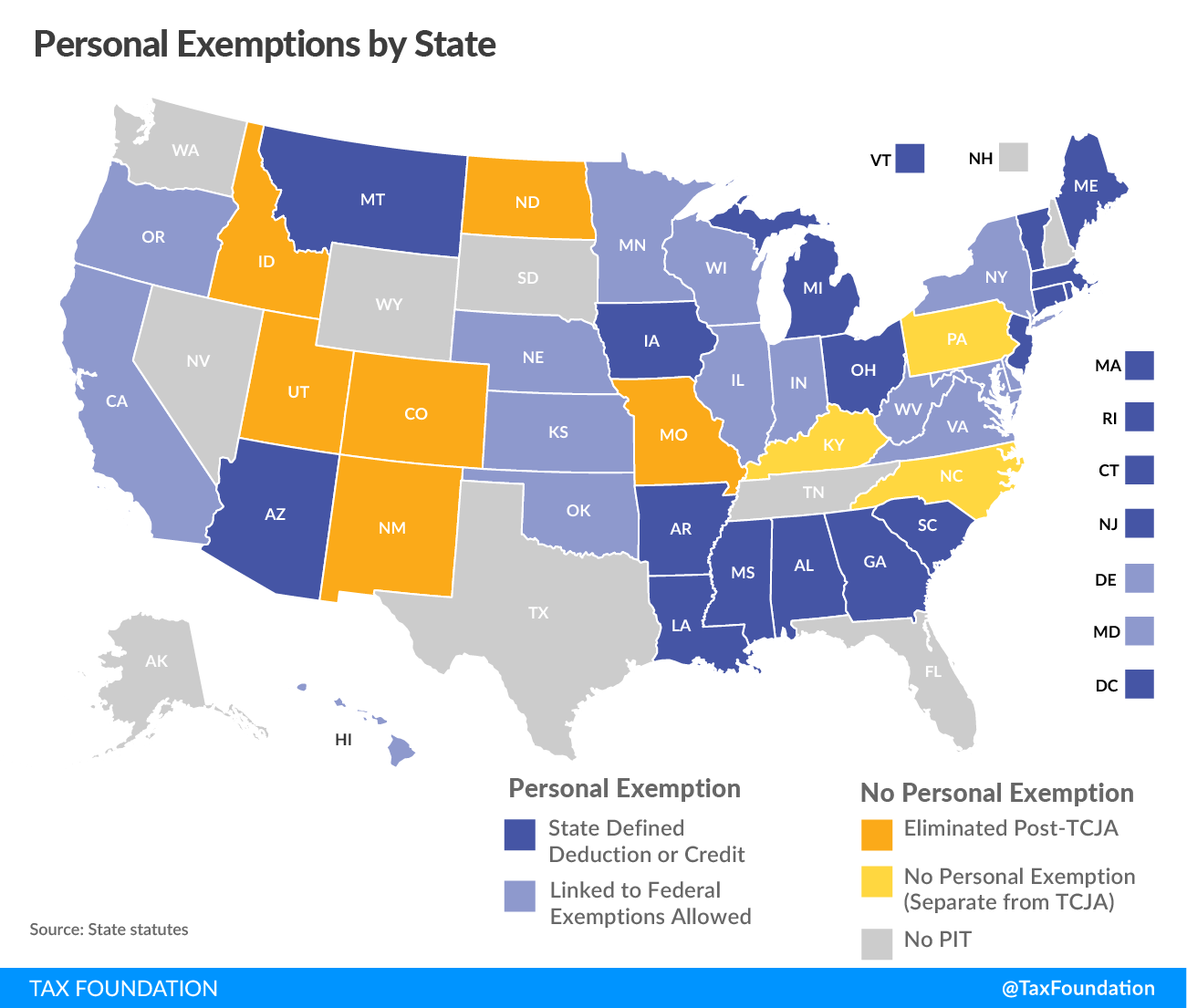

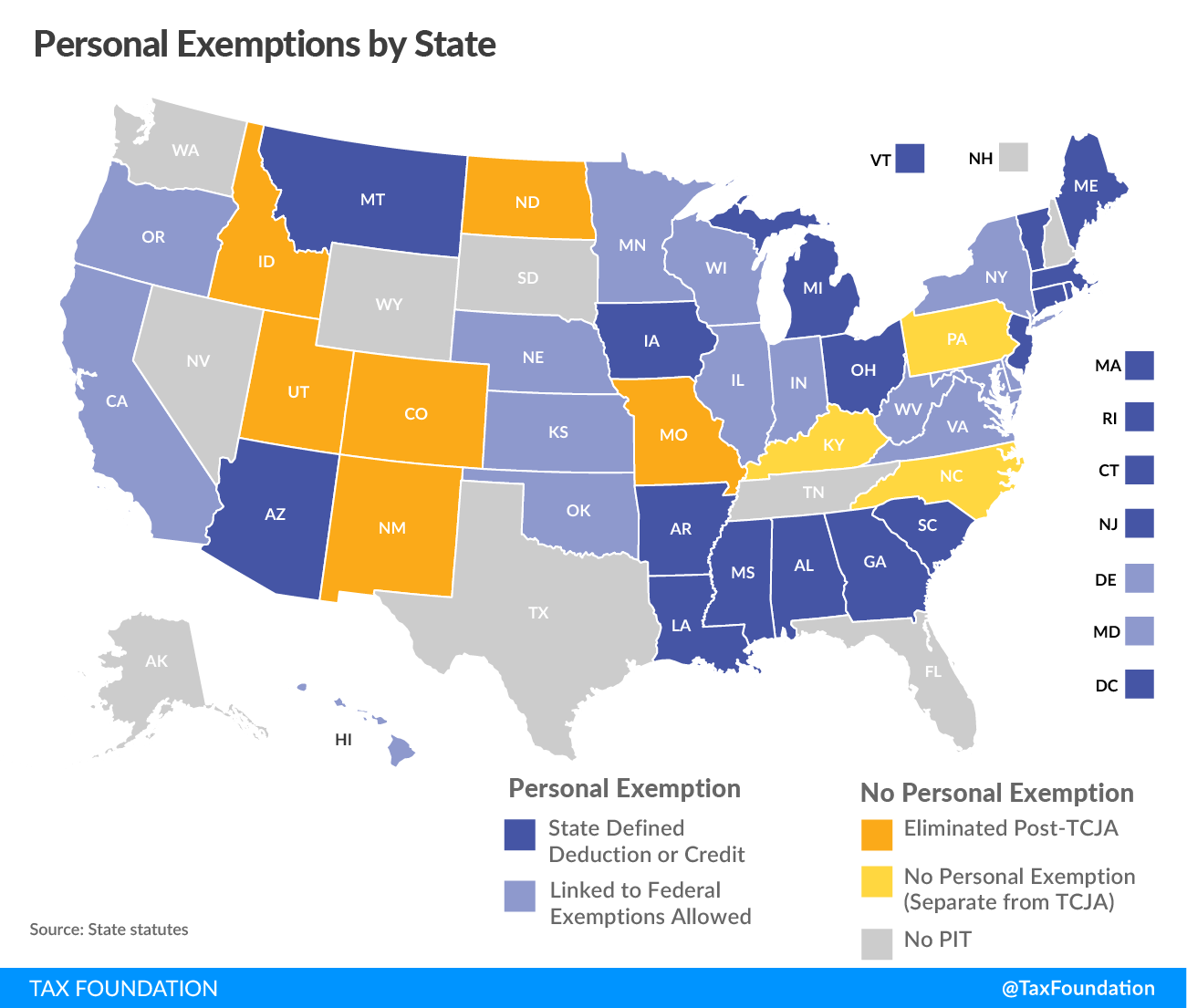

With tax year 2018 in the books, six states which previously offered personal exemptions eliminated them in line with federal law, while a seventh state (Kentucky) eliminated its personal exemption as part of a broader tax reform. Five states took legislative action to restore a personal exemption that would have been eliminated otherwise. Another thirteen states which reference federal law in the calculation of their own personal exemptions already did so in such a way as to preserve the exemption for state filers.

Implications of the TCJA

For states which conform to other changed federal income tax provisions, like the higher standard deduction, the ramifications were straightforward. The personal exemption was another matter altogether, largely the result of the procedures under which federal tax reform was adopted.

The TCJA was enacted as a reconciliation bill, under Senate rules which limit debate and amendments for budget reconciliation measures. The reconciliation process made it easier to enact tax reform, but it came at a cost of legislative flexibility. Many individual income tax provisions, in particular, are temporary, yielding provisions that are zeroed out rather than repealed out. The personal exemption statute is still necessary, as it might be restored in 2026. Hence, Congress reduced its value to $0 but retained it in law.

For the handful of states which conformed to the federal personal exemption without any modifications, the consequence was straightforward: elimination. Many states, however, substituted different dollar values for the personal exemption, but used federal definitions to determine eligibility of those exemptions. After enactment of TCJA, seemingly inconsequential differences in the wording of those provisions could mean the difference between offering or denying an exemption at the state level.

In some states, a deduction or exemption is provided for each filer, spouse, and dependent, in an amount set by the state. More frequently, states establish a personal exemption amount that might differ from what the federal government offered—$2,250 in Kansas, for instance, or $1,000 in Michigan—and then provide a state exemption, in that amount, for each exemption allowed the taxpayer under the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). In other cases, states incorporate all federal exemptions claimed.

Using definitions of dependents preserves state exemptions, as does tying the state exemption to the number of exemptions allowable under federal law. Here, California is typical, offering exemptions for filers and “for each dependent … for whom an exemption is allowable under Section 151(c) of the Internal Revenue Code.”[1] Under federal law, exemptions are still allowable, though they are worth $0 for federal tax purposes. California’s personal exemptions, therefore, remain in place.

“Allowable,” however, is just one of many ways that states reference the IRC’s treatment of personal exemptions. Other states key in on the number of exemptions an individual can lawfully claim (Delaware), dependents as defined in IRC § 152 (Maryland), the number of exemptions for which a taxpayer is entitled to a deduction (New York), the number of deductions allowed for personal exemptions (Maine, formerly), or the number of exemptions allowable on the filer’s income tax return (Michigan, formerly), to name a few variations.

Each has a slightly different meaning, and potentially a different outcome. Unsurprisingly, the initial result was uncertainty, with lawmakers, administrators, and tax professionals sometimes unsure, and occasionally at odds on, whether a given state’s personal exemption could be claimed for tax year 2018. As tax season approaches, though, states have clarified the status of their personal exemptions.

Table 1. State Conformity to Federal Personal Exemtdtion Provisions

|

Notes: Minnesota conforms to federal policy, but still uses the IRC as it existed in 2016 and thus retains the personal exemption. Three states (KY, NC, PA) impose wage income taxes but lack a personal exemption. Nine states forgo a tax on wage income.

Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg Tax; Tax Foundation research

|

| State-Defined Exemption |

Linked to Exemptions Allowed |

Conforms to Federal (Eliminated) |

Alabama

Arizona

Connecticut

Georgia

Louisiana

Maine

Massachusetts

Michigan

Mississippi

Montana

Ohio

Rhode Island

South Carolina

Vermont

District of Columbia

|

California

Delaware

Hawaii

Illinois

Indiana

Kansas

Maryland

Nebraska

New York

Oklahoma

Oregon

Virginia

West Virginia

Wisconsin

|

Colorado

Idaho

Missouri

New Mexico

North Dakota

Utah

|

Lawmakers in Maine, Michigan, South Carolina, Vermont, and West Virginia amended their tax codes to retain personal exemptions that might otherwise have been eliminated. In Michigan, for instance, state law previously provided that the state’s personal exemption amount was to be “multiplied by the number of personal or dependency exemptions allowable on the taxpayer’s federal income tax return pursuant to the Internal Revenue Code.” Given that such exemptions, while allowable under the IRC, no longer appear on federal income tax returns, lawmakers took action. Specifically, they took federal definitions out of the equation: “A taxpayer may claim a dependency exemption for each individual who is a dependent of the taxpayer for the tax year.”[2]

In Missouri, legislators took the opposite course, resolving an ambiguity (“if he or she is entitled to a deduction for such personal exemptions for federal income tax purposes”) in favor of the clear elimination of the personal exemption, albeit as part of a larger tax package which reduced income tax rates and provided other tax relief.[3]

Two other states, West Virginia and Kansas, illustrate just how unclear the ramifications of such legislative language can be. Both states, like Missouri, referenced being entitled to a deduction for personal exemptions. West Virginia’s code provided a deduction for “each exemption for which he or she is entitled to a deduction for the taxable year for federal income tax purposes,” and policymakers, fearful that it was insufficient to retain the personal exemption, adopted new legislation stipulating that the phrase means “the exemption the person would have been allowed to claim for the taxable year had the federal income tax law not been amended to eliminate the personal exemption for federal tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2018.”[4] In Kansas, by contrast, similar language (“for each exemption for which such individual is entitled to a deduction for the taxable year for federal income tax purposes”[5]) has been understood to preserve the state’s personal exemption.

Thus, while states have settled on their interpretations for tax year 2018, the language of these statutes could continue to matter in the coming years—and, in particular, the choices states make now will have implications in 2026, should the new federal law be allowed to expire.

The following table delineates the statutory language used by states which rely on federal definitions of eligibility but have nonetheless been understood to retain their own personal exemptions. Of these, two states—California and Virginia—have yet to conform to the new federal law, though their personal exemptions should be unaffected when they do.

Table 2. Statutory Linkages to the Federal Personal Exemption

|

Sources: State statutes; Tax Foundation research

|

| State |

Statutory Provision |

Conformity |

|

California

|

Taxpayer, spouse, and “for each dependent (as defined in Section 17056) for whom an exemption is allowable under Section 151(c) of the Internal Revenue Code.”[6]

|

X

|

|

Delaware

|

“for each personal exemption to which such individual is entitled for the taxable year for federal income tax purposes”[7]

|

✓

|

|

Hawaii

|

“the number of exemptions which the individual can lawfully claim under the Internal Revenue Code”[8]

|

✓

|

|

Illinois

|

Taxpayer, spouse, and “an additional exemption equal to the basic amount for each exemption in excess of one allowable to such individual taxpayer for the taxable year under Section 151 of the Internal Revenue Code”[9]

|

✓

|

|

Indiana

|

“each of the exemptions provided by Section 151(c) of the Internal Revenue Code (as effective January 1, 2017)”[10]

|

✓

|

|

Kansas

|

“for each exemption for which such individual is entitled to a deduction for the taxable year for federal income tax purposes”[11]

|

✓

|

|

Maryland

|

Taxpayer, spouse, and “for each dependent, as defined in § 152 of the Internal Revenue Code”[12]

|

✓

|

|

New York

|

“for each exemption for which he is entitled to a deduction for the taxable year under section one hundred fifty-one(c) of the Internal Revenue Code”[13]

|

✓

|

|

Oklahoma

|

“personal exemptions allowed by the Internal Revenue Code”[14]

|

✓

|

|

Oregon

|

“the number of personal exemptions allowed under section 151 of the Internal Revenue Code”[15]

|

✓

|

|

Virginia

|

“for each personal exemption allowable to the taxpayer for federal income tax purposes”[16]

|

X

|

|

West Virginia

|

“the exemption the person would have been allowed to claim for the taxable year had the federal income tax law not been amended to eliminate the personal exemption for federal tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2018”[17]

|

✓

|

|

Wisconsin

|

Taxpayer, spouse, and “for each dependent, as defined under section 152 of the Internal Revenue Code, of the taxpayer”[18]

|

✓

|

Minnesota is the only state in which the retention of the personal exemption is indisputably contingent on the state’s conformity date. The state’s tax starting point is federal taxable income, which includes the federal standard deduction and (zeroed-out) personal exemption.[19] However, legislators punted in 2018, with the state’s tax code still tied to the IRC as it existed prior to federal tax reform. As such, the personal exemption is retained—for now.

Virginia also offers a degree of uncertainty. Although lawmakers updated the state’s conformity date during the last legislative session, they expressly excluded most of the provisions of the TCJA, leaving those for later consideration. The statute on the books is ambiguous, providing a state exemption for each personal exemption allowable for federal income tax purposes. There is no question that these exemptions are still allowable, though they no longer have an income tax purpose and do not appear on federal tax forms. Nevertheless, tax officials in Virginia have signaled that the personal exemption will be retained.

In most states, conformity to federal tax changes results in additional revenue, since many of the base-broadening provisions are incorporated into state tax codes, while corresponding rate reductions are not. The elimination of the personal exemption is part of that puzzle, and is particularly significant in states like New Mexico, which is expected to finish the current fiscal year with $1.4 billion in excess revenue, largely due to the growth of the state’s oil sector, but with a substantial assist by tax base broadening.[20]

Conclusion

When these state tax provisions were written, there was no reason to anticipate a $0 federal personal exemption; variations in statutory text which loom large now were insignificant when adopted. States which have eliminated the personal exemption should consider offsetting reductions, to the extent that they have not already done so. States which currently diverge from federal treatment might consider aligning with the new federal law as a pay-for to facilitate reforms. And where any ambiguity remains, legislators should seek to address it. Federal tax reform creates many opportunities for states to reform their tax codes. It also, at times, requires efforts to enhance clarity.

Notes

[1] Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 17054(d)(1)(A).

[2] M.C.L.A. 206.30(2).

[3] Jared Walczak, “Missouri Governor Set to Sign Income Tax Cuts,” Tax Foundation, July 11, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/missouri-governor-set-sign-income-tax-cuts/.

[4] WV Sec. 11-21-9(f).

[5] KS Sec. 79-32,121.

[6] Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 17054(d)(1)(A).

[7] 30 Del.C. § 1110(b).

[8] HRS § 235-54.

[9] 35 ILCS 5/204(c).

[10] IC 6-3-1-3.5.

[11] K.S.A. 79-32,121.

[12] MD Code, Tax – General, § 10-211(1)(a).

[13] McKinney’s Tax Law § 616(a).

[14] 68 Okl.St.Ann. § 2358(E).

[15] O.R.S. § 316.085(1)(a).

[16] VA Code Ann. § 58.1-322.03(2).

[17] W. Va. Code, § 11-21-9(f).

[18] W.S.A. 71.05(23)(b).

[19] M.S.A. § 290.01(19).

[20] Morgan Lee, “Oil Sector Boosts State Government Fortunes in New Mexico,” Associated Press, Dec. 11, 2018, https://www.lcsun-news.com/story/news/local/new-mexico/2018/12/11/new-mexico-oil-gas-boom-state-government-funding-budget-surplus-revenue-economy-education/2272929002/.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – The Status of State Personal Exemptions a Year After Federal Tax Reform

by r Hampton | Feb 6, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Resisting the Allure of Gross Receipts Taxes: An Assessment of Their Costs and Consequences

Key Findings

- Gross receipts taxes, also known as “turnover taxes,” have returned as a revenue option for policymakers after being dismissed for decades as inefficient and unsound tax policy. Their appeal comes as many states are looking to replace revenue lost by eroding corporate income tax bases and as a way to limit revenue volatility. Five states impose gross receipts taxes statewide, while eight more considered proposals to enact a gross receipts tax over the past two years.

- Taxes on gross receipts are enticing to policymakers because the broad tax base brings a large, stable source of revenue to state governments. Proponents argue that gross receipts taxes are simpler to administer and calculate than corporate income taxes.

- Business-to-business transactions are not exempt from gross receipts taxes, which creates tax pyramiding. The same economic value is taxed multiple times—once during each transaction through the stages of production—which compounds the tax’s economic effects. This distorts economic decision-making, incentivizing firms to vertically integrate, change industries, and leave the taxing jurisdiction.

- Gross receipts taxes impact firms with low profit margins and high production volumes, as the tax does not account for a business’ costs of production. Startups and entrepreneurs, who typically post losses in early years, may have difficulty paying their tax liability.

- Gross receipts taxes impose costs on consumers, workers, and shareholders. Prices rise as the tax is shifted onto consumers, impacting those with lower incomes the most. Some firms may lower wages to accommodate the tax, reducing incomes. Other job opportunities may be limited as well.

- Efforts to mitigate the negative effects of gross receipts taxes, such as creating multiple rates for different industries, often increase the tax’s complexity, negating one of the primary reasons given to enact the tax.

- States should consider alternatives to gross receipts taxes given the economic distortions they impose, their lack of transparency, and their complexity in practice. Well-structured sales taxes can provide reliable revenue with fewer economic costs. In addition, states should consider reforms to their corporate income tax bases.

Introduction

Gross receipts taxes are applied to receipts from a firm’s total sales. Unlike a corporate income tax, these taxes apply to the firm’s sales without deductions for a firm’s costs. They are not adjusted for a business’ profit levels or expenses and apply to all transactions a business makes. Unlike a sales tax, gross receipts taxes apply to business-to-business transactions in addition to final consumer purchases.

Having fallen out of favor in the mid-20th century, gross receipts taxes are making a comeback across the country to raise revenue. Known as “turnover taxes,” gross receipts taxes are a form of business taxation. While gross receipts taxes have been a tempting source of revenue for states and municipalities, they impose significant costs on the firms, consumers, and workers.

This paper will provide historical context on gross receipts taxes, a discussion of the allure they carry with policymakers, and their economic costs and consequences. Proponents of these taxes make arguments that may seem compelling to policymakers looking for stable and large revenue sources, but this comes with a Faustian bargain. Taxes on gross receipts generate economic distortions and impose costs in excess of their perceived benefits.

The History and Resurgence of Gross Receipts Taxes

Taxes on gross receipts originated in Europe as early as the 13th century.[1] They were an important revenue source for France and Germany in the early 20th century but were later replaced with value-added taxes in the 1960s and 1970s.[2] In America, the first gross receipts tax was established in 1921 by West Virginia as a “business and occupations privilege” tax.[3]

Gross receipts taxes spread during the 1930s, as the Great Depression reduced the revenue states collected from property and income taxes.[4] Fifteen states adopted taxes on gross receipts by 1934.[5] By the late 1970s, however, gross receipts taxes began to be repealed or struck down as unconstitutional by courts, hastening their decline as a tool for raising revenue. By 2002, only Washington State’s Business & Occupations (B&O) tax and gross receipts taxes in Delaware and Indiana survived from the 20th century.[6]

Starting in the mid-2000s, several states began to explore gross receipts taxes as a method to increase revenue. In 2002, New Jersey implemented a gross receipts tax as an alternative minimum assessment for business taxes. Kentucky and Ohio enacted their own taxes on gross receipts in 2005, followed by Michigan’s newly levied Michigan Business Tax (MBT) in 2008.[7] Kentucky and New Jersey established their taxes on gross receipts as an alternative minimum tax on businesses, partially in response to falling corporate income tax revenues.[8]

The enactment of Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax (CAT) represents a turning point in the modern history of gross receipts taxes, as its design would be used as a source of inspiration for states looking for alternative revenue sources. The CAT replaced the state’s previous corporate franchise tax and a tax on tangible personal property. Both of those taxes were harmful to the business community in Ohio, which helped motivate the switch to a gross receipts tax.[9] Ohio’s CAT was specifically referenced in the subsequent policy debate around the design of failed gross receipts tax proposals in other states, such as in Missouri, Oregon, and West Virginia in 2017.[10],[11]

The gross receipts taxes created economic problems for enacting states. In New Jersey, calls to repeal the tax grew less than a year after it came into effect due to the perceived lack of fairness, as the tax applied to businesses unequally.[12] Subsequently, the assessment in New Jersey began to sunset in 2006. Kentucky repealed its alternative minimum tax in 2006 after the chief state forecaster in the state budget director’s office found that the tax reduced investment and harmed small businesses.[13] Michigan also repealed the MBT in 2011, replacing it with a flat corporate income tax.[14]

Despite the experiences of these states, gross receipts taxes have made a resurgence in the last five years. In 2015, Nevada create its Commerce Tax, which followed a failed attempt to enact a gross receipts tax via a ballot initiative in 2014.[15] In addition to Missouri, Oregon, and West Virginia, gross receipts tax proposals were also considered in California, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Wyoming in the past two years.[16]

Gross receipts taxes have returned as states are looking for reliable sources of revenue. Corporate income taxes have proven volatile, with eroding tax bases as a result of various tax deductions, carveouts, and other expenditures. Several states have considered adding a gross receipts tax as an alternative minimum to a state’s corporate income tax, such as the now-expired taxes in Indiana, Kentucky, and New Jersey.[17]

Existing Gross Receipts Taxes

A gross receipts tax is levied on the sales a firm makes before accounting for its costs. Some states apply the tax above a gross receipts threshold. For example, in Ohio, a business’ first $1 million in gross receipts is exempt from the tax, while gross receipts above $1 million are subject to a 0.26 percent rate. States may also impose minimum tax liabilities. In Ohio, businesses are subject to a minimum tax liability ranging from $150 for filers with less than $1 million in gross receipts to $2,600 for filers with more than $4 million in gross receipts.[18]

A key feature of gross receipts taxes is the inclusion of business-to-business transactions in the tax base. Most states also include some business inputs in their sales tax bases, whether it be explicitly defined in statute or inadvertently.[19] New Mexico, Hawaii, North Dakota, and South Dakota have broad bases that include many business-to-business transactions.[20] Sales taxes with overly-broad bases should be distinguished from gross receipts taxes. The latter tax explicitly aims to tax business inputs, while sales taxes have not properly exempted those inputs from the tax base.

Table 1. Overview of Statewide Gross Receipts Tax Rates

|

Source: State statutes and departments of revenue.

|

| State |

GRT Name |

No. of Rates |

Lowest Rate |

Highest Rate |

|

Delaware

|

Gross Receipts Tax

|

54 |

0.0945% |

0.7468% |

|

Ohio

|

Commercial Activity Tax

|

1 |

0.26% |

0.26% |

|

Texas

|

Franchise (Margin) Tax

|

3 |

0.331% |

0.75% |

|

Nevada

|

Commerce Tax

|

27 |

0.051% |

0.331% |

|

Washington

|

Business & Occupation (B&O) Tax

|

35 |

0.13% |

3.3% |

The tax base and expenditures may vary depending on the design of the gross receipts tax. Texas, for example, allows for deductions for cost of goods sold (COGS) or worker compensation, while Nevada permits firms to deduct 50 percent of a firm’s Commerce Tax liability over the previous four quarters from payments for the state’s payroll tax.[21] Gross receipts taxes usually apply to C corporations, but some, such as Texas’ Margin Tax, apply to C corporations and pass-through firms such as LLCs and S corporations.[22]

Nearly all states use gross receipts as a tax base in some context, most commonly for utility and energy companies.[23] Gross receipts taxes also exist at the municipal and county levels. Municipalities in several states, such as California, Pennsylvania, Washington, West Virginia, and Virginia levy gross receipts taxes. These local-level gross receipts taxes are often framed as a business license tax, such as Virginia’s local-option Business, Professional, and Occupational Licenses (BPOL) tax.

Each state varies the number of rates for its gross receipts tax. Ohio’s CAT levies one rate, 0.26 percent, on all gross receipts. Washington, by contrast, has 35 rates ranging from 0.13 percent to 3.3 percent. States often designate multiple rates, typically by industry, to mitigate some of the economic costs associated with taxes on gross receipts.

Arguments for Gross Receipts Taxes

Advocates of gross receipts taxes argue that they are simple to administer and collect, provide a stable source of revenue, and levy a low tax rate on firms.

Gross receipts taxes can be simpler to administer and calculate than corporate income taxes, as a firm does not have to consider its costs when deriving its gross receipts tax liability.[24] States considering a gross receipts tax often point to this advantage. For example, Missouri’s Governor’s Committee on Simple, Fair, and Low Taxes argued that “the inherent difficulties, volatility, complexity in implementation and narrow tax base all make the corporate tax unpalatable.” The committee recommended replacing it with a gross receipts tax.[25] This argument has become more popular as the corporate income tax base has eroded from tax expenditures and revenue collection has declined.

In addition to its perceived simplicity, gross receipts taxes provide a stable source of revenue. Gross receipts taxes have broad bases, especially when compared to the corporate income tax. Corporate income taxes often suffer volatility as a result of the business cycle; firms may realize losses during a recession and not have any taxable income. Gross receipts taxes, on the other hand, provide revenue from every receipt a firm receives, regardless of its profit level. Revenue collection is more predictable. An empirical estimate of the revenue stability of Washington’s B&O tax found that it is more stable than taxes on corporate or individual income but less stable than the retail sales tax.[26]

Gross receipts taxes tend to have lower rates than other taxes to raise any given amount of revenue, due to their overly broad tax base.[27] For example, Ohio’s CAT, set at 0.26 percent, raises 6.3 percent of the state’s own-source tax revenue and 11.6 percent of the amount generated by Ohio businesses by the federal corporate income tax.[28] The low statutory tax rate set for gross receipts taxes may make them easier for policymakers to introduce than other kinds of taxes, as they may receive less pushback from other stakeholders and constituents when they see the low headline rate.

Ohio’s CAT also illustrates another argument proponents make: gross receipts taxes may be superior to poorly structured alternative taxes.[29] The CAT replaced the state’s Corporate Franchise Tax (CFT), a business privilege tax, and a tangible personal property (TPP) tax, in stages between 2005 and 2010. The phaseout of these taxes also included a 21 percent reduction in income tax rates.[30] Businesses perceived the tax swap to be a net benefit given the economically damaging effect of the CFT and the tangible personal property tax. While it is arguable that Ohio improved its tax climate by eliminating the CFT and TPP, imposing a gross receipts tax represents a missed opportunity to raise revenue using a replacement that imposes fewer economic costs.

Negative Economic Effects of Gross Receipts Taxes

Despite the perceived simplicity, stability, and low rate provided by gross receipts taxes, they create negative economic effects that more than outweigh these advantages. In fact, attempts to lessen the economic costs of gross receipts taxes often negate the advantages they pose.

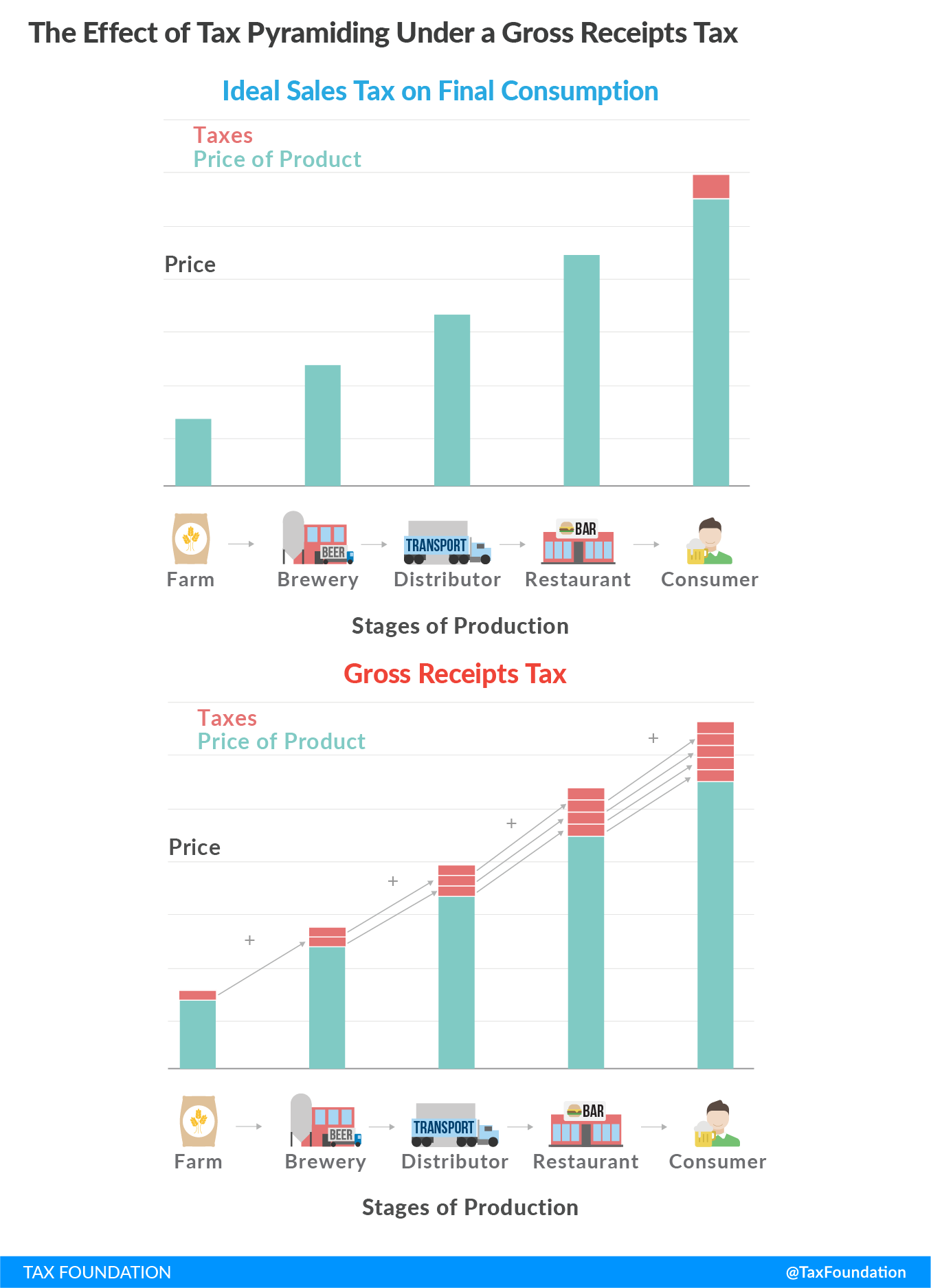

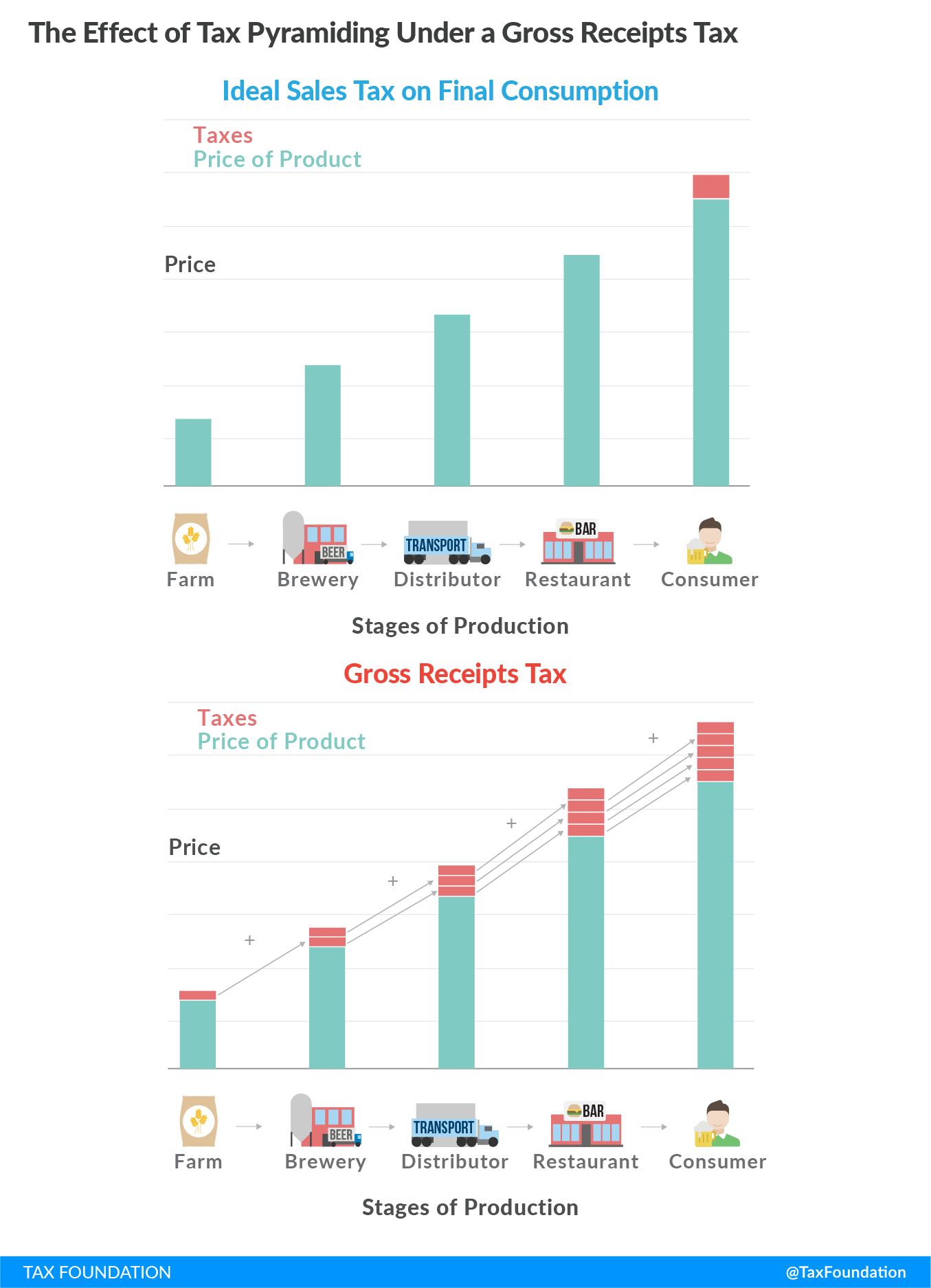

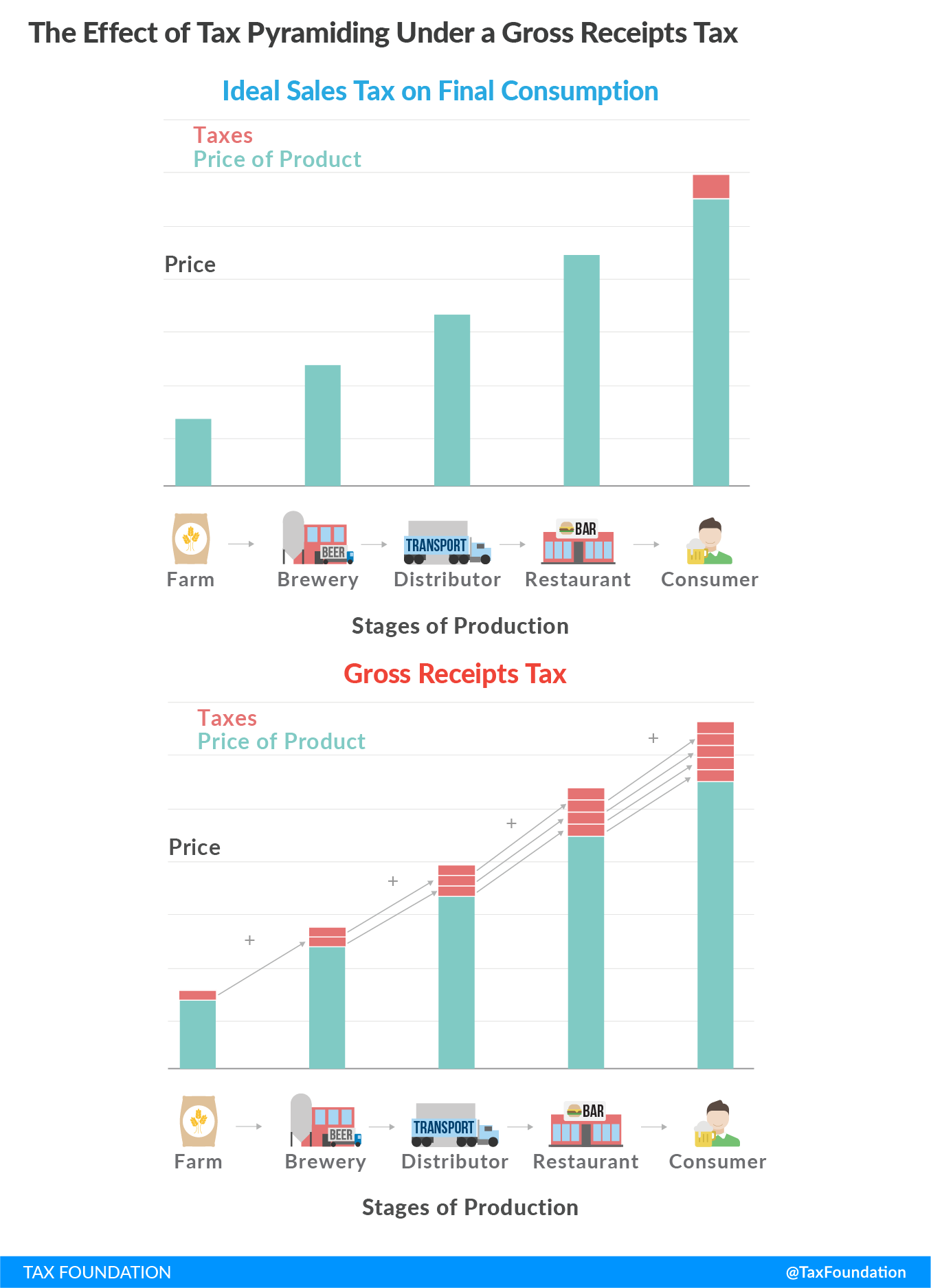

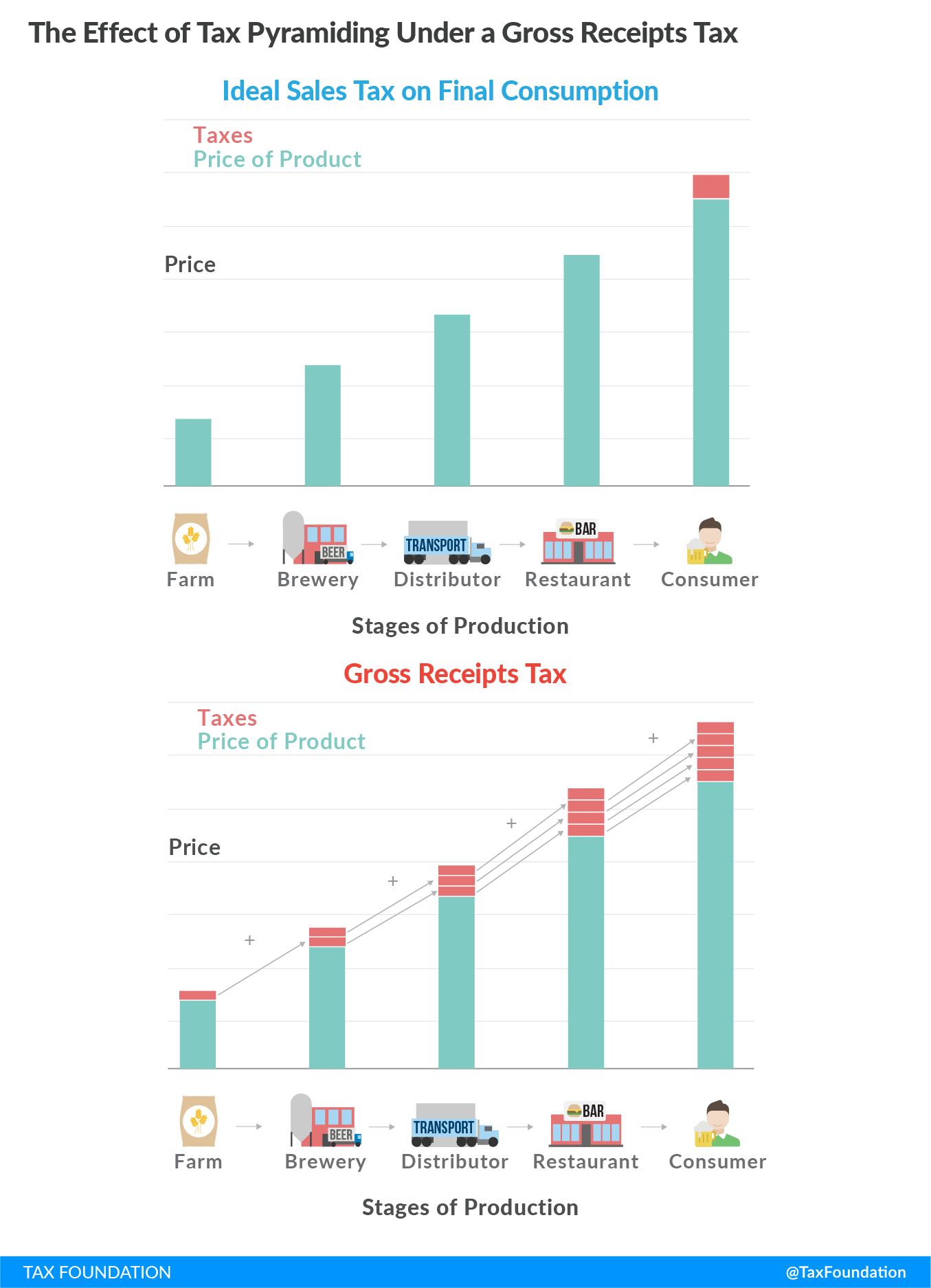

Tax Pyramiding

Gross receipts taxes deviate from sound tax policy by levying a tax on the same economic value multiple times in the production process. This phenomenon is known as tax pyramiding, which distorts economic activity and can magnify effective tax rates.[31]

Ideally, a sales tax would apply to all final personal consumption. Gross receipts taxes diverge from sales taxes by levying a tax on each transaction at each stage of production. Legally, the business earning receipts is responsible for calculating and remitting its gross receipts tax liability to the state. However, the tax affects firms’ economic decisions in response to the tax.

A producer could shift the cost of the tax forward onto the buyer of her products by increasing the products’ prices. If the tax is passed along to buyers, the economic incidence of the tax reverberates through the production system. If a producer cannot shift the cost of the tax onto the buyer, she may lower worker compensation or reduce profits paid to shareholders.

The amount of the tax that is passed along to the purchaser is determined by how sensitive the purchaser is to the increase in price; sellers will be more inclined to raise prices on buyers who are less likely to reduce their purchases by switching to suitable alternatives. At each stage, another tax is levied on the seller’s gross receipts, which compounds the effective tax paid. By the time the product reaches the final consumer, the value of the product has been taxed at each stage of production.

For example, take the process required to produce a dresser. When a logger sells wood to a lumberyard, the tax is applied to the receipt collected by the logger. The logger may raise the price of the product to accommodate the tax, which shifts the cost of the tax onto the lumberyard. When the lumberyard processes the wood into lumber and sells it to a furniture manufacturer, they incorporate the cost of the tax when determining its price. Included in the sale price to the manufacturer is the already-taxed value provided by the logger, which is taxed again when the manufacturer purchases it. This is compounded when a furniture store buys the dresser from the manufacturer and ends when a consumer purchases the dresser from the furniture store.

Contrast the pyramiding process with a well-designed sales tax. In the case of a dresser, the business-to-business transactions needed to produce the dresser are not taxed. The tax is applied once, when the consumer purchases the dresser, and no tax pyramiding occurs (see Figure 1).

Tax pyramiding creates several economic distortions. Tax pyramiding increases effective tax rates, as the statutory tax rate is applied to the same economic value multiple times and a portion of the tax is shifted forward to the next stage of production. For example, a 0.5 percent statutory tax rate on gross receipts could pyramid to an effective tax rate of 1.25 percent (see Table 2).

Businesses at each stage will only see the statutory rate and will not see that the price is higher than it would be otherwise due to the tax levied at the earlier production stages. Consumers will face higher prices but will not know that the price increase is due to tax pyramiding.

Table 2. Tax Pyramiding in a Hypothetical Furniture Production Process

|

Note: Effective Tax Rate on the Furniture ($1.25/$100): 1.25 percent

|

| Furniture Production Stage |

Cost of Business Inputs |

Value Added |

Sale Price for Next Production Stage |

Tax on Gross Receipts (0.5 percent)[32] |

|

Logger

|

$0 |

$25 |

$25.00 |

$0.12 |

|

Lumberyard

|

$25.12 |

$25 |

$50.12 |

$0.25 |

|

Manufacturer

|

$50.37 |

$25 |

$75.37 |

$0.38 |

|

Furniture Store (Sale to Consumer)

|

$75.75 |

$25 |

$100.75 |

$0.50 |

|

Total

|

|

$100 |

|

$1.25 |

The degree of tax pyramiding in an industry will depend on how many production stages occur before a good or service is consumed.[33] Industries with longer production cycles tend to have higher effective tax rates and more tax pyramiding under a gross receipts tax, as the value produced by those industries is taxed more frequently. Tax pyramiding also occurs more in industries where value is added earlier in the production process, as the value is taxed more times in the production process than value added in a later stage of production.[34]

Empirical estimates of tax pyramiding have found that it may vary widely by industry. This is intuitive, as each industry may have different average lengths of production. In 2002, Washington State’s Tax Reform Commission found that the state’s B&O tax pyramids 2.5 times on average, but this varies from 1.4 times for many service industries and up to 6.7 times for some manufacturing industries (see Table 3 for selected industries).[35]

Table 3. Tax Pyramiding in Washington State’s Business & Occupation (B&O) Tax

|

Source: Washington State Tax Structure Study Committee, Table 9-7, “A Measure of Pyramiding of the B&O Tax,” in “Tax Alternatives for Washington State: A Report to the Legislature,” Volume 1, November 2002,112.

|

| Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) Code |

Sector |

Pyramiding Index |

|

Food (20)

|

Manufacturing

|

6.7

|

|

Petroleum Refining (29)

|

Manufacturing

|

6.7

|

|

Rubber & Plastics (30)

|

Manufacturing

|

4.3

|

|

Apparel & Textiles (22-23)

|

Manufacturing

|

4.1

|

|

Construction (15-17)

|

Construction

|

3.3

|

|

Electronic & Electrical Equipment (36)

|

Manufacturing

|

2.8

|

|

Transportation (40-47)

|

Transportation & Public Utilities

|

2.5

|

|

Mining & Quarry (10-14)

|

Mining

|

2.4

|

|

Fabricated Metal Products (34)

|

Manufacturing

|

2.3

|

|

Personal Services (72)

|

Services

|

2.1

|

|

Agriculture, Forestry, & Fishing (1-9)

|

Agriculture, Forestry, & Fishing

|

2.0

|

|

Automotive Repair, Services, & Parking (75)

|

Services

|

2.0

|

|

Communications (48)

|

Transportation & Public Utilities

|

1.9

|

|

Wholesale Trade (50-51)

|

Wholesale Trade

|

1.9

|

|

Legal, Accounting, & Related Services (81-89)

|

Services

|

1.8

|

|

Retail Trade (52-59)

|

Retail Trade

|

1.6

|

|

Health Services (80)

|

Services

|

1.6

|

|

Finance, Insurance, & Real Estate (60-67)

|

Finance, Insurance, & Real Estate

|

1.6

|

|

Electric, Gas, & Sanitary Services (49)

|

Transportation & Public Utilities

|

1.5

|

|

Statewide

|

|

2.5

|

Manufacturers tend to be disadvantaged by a gross receipts tax as the pyramiding occurs through the production and distribution process.[36] The wide variation in tax pyramiding provides some industries with relative advantages over others, which distorts the decisions of prospective entrants and diverts economic resources away from their most highly-valued use.

A firm may not necessarily shift a gross receipts tax onto subsequent production stages. Alternatively, businesses could lower wages for workers or lower the profits that are distributed to shareholders. Firms may use a combination of these approaches. For example, firms could raise prices in partial response to the tax while lowering worker wages. If businesses lower wages and distributed profits but do not raise prices, tax pyramiding is limited or prevented.

There is evidence that most of the costs associated with a gross receipts tax are forward-shifted to the subsequent production stages. Before Canada moved to a value-added tax, several provinces had poorly-designed sales taxes that did not exempt business inputs, meaning that they functioned like a gross receipts tax. Michael Smart and Richard Bird of the University of Toronto found that the forward-shifting of the tax burden on those transactions approached 100 percent.[37] While this does not directly examine forward-shifting of gross receipts taxes, this suggests that firms often will pass the incidence of the tax down onto buyers when they incur tax costs on business inputs.

Impact on Profit Margins and Production Volumes

Gross receipts taxes do not account for a firm’s profit or net income, and therefore have greater impacts on firms with lower profit margins. Two firms bringing in an equivalent volume of gross receipts may face different costs and have different profit margins, yet they face the same tax lability. This penalizes the firms’ low profit margins, driving up their effective tax rate. As economist John Mikesell frames it, “Gross receipts by itself is not an acceptable guide for the affluence and economic ability of an entity.”[38]

The professional services firm EY examined effective tax rates for Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax across different industries, finding rates varying from 0.4 percent for holding companies to 8.3 percent for wholesalers with less than $10 million in taxable receipts, compared to the statutory rate of 0.26 percent for all firms.[39]

Industries with lower ratios of profits to receipts tend to have higher effective tax rates; this is expected, as firms in industries with lower profit margins will see a greater share of their net income be remitted to pay the tax. This is before accounting for tax pyramiding, which increases the effective tax rate further. Wholesalers may experience a tax rate equal to 15.8 percent of net income under Ohio’s CAT after accounting for tax pyramiding, for example.[40] Differences in the profits to receipts ratio and lengths of production between industries create varying average effective tax rates. Using Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data, EY found that the average effective tax rate varies up to 3 percent between industries.[41]

Varying effective tax rates introduce significant economic distortions, as firms will adjust their behavior on the margin to avoid higher effective tax rates. As economists Andrew Chamberlain and Patrick Fleenor argue, “Investors in the economy are sensitive to rates of return in different industries, and small differences in effective tax rates can mean the difference between starting a company in one industry and abandoning another.”[42]

The statutory rate for gross receipts taxes should not be compared to tax rates on other tax bases and cannot be used as an effective argument in favor of levying a gross receipts tax without considering the effective tax rate on firms and consumers. A firm with a profit margin of 1 percent under Ohio’s CAT bears a 26 percent effective tax rate on corporate net income.[43] As Tax Foundation’s Jared Walczak explains, “This is notable given that some industries run on average profit margins of just a few percent, and of course some companies experience actual losses.”[44]

Startups and entrepreneurial ventures may also be disproportionately affected by gross receipts taxes. Startups often spend years before reaching profitability, but these firms will still owe a tax liability on their gross receipts, which could pose problems if the firm does not have adequate liquidity to pay the tax. A gross receipts tax could complicate how firms cover the added cost before they realize an uncertain long-term return. Some firms may never become profitable. By contrast, incumbents with higher profit margins have less difficulty finding funds to fulfill their tax liability.

Firms with high production volumes (and therefore more transactions subject to a gross receipts tax) are taxed at higher effective rates than comparable firms with lower volumes. Manufacturers, grocers, and retailers bear a disproportionate tax burden given their high number of transactions. The same could be said of firms with lower volumes but very expensive products, such as pharmaceutical companies. There is no sound tax basis for penalizing high-volume businesses or expensive products, which only distorts their decisions to invest in high-volume endeavors and lessens economic efficiency.

Gross receipts taxes also bias firms “against the use of capital in the production process: it must be paid on capital when it is produced but not on labor, so it encourages substitution of labor for capital in the production process.”[45] Capital-intensive industries and businesses will feel the brunt of gross receipts taxes, as the tax is applied to capital and passed onto the buyer when it is purchased. This may encourage firms on the margin to swap out capital investments for more labor, which may be less efficient and lead to lesser economic growth.

Incentives for Firms to Vertically Integrate and Insource

Tax pyramiding changes the economic decisions firms make to reduce their tax exposure. Sound tax systems raise revenue without influencing the economic decision-making of market actors. Decisions to consume, invest, and work should not be made because of how something is taxed. Gross receipts taxes change firm behavior on several margins, including decisions to outsource and merge with other firms.

Firms within industries with longer production chains can reduce their exposure to gross receipts taxes by integrating vertically.[46] A firm that merges with a business that regularly sells to them can avoid the tax, as the firm no longer engages in a taxable transaction. This gives the firm an advantage over competitors who incur the tax. Vertical integration incentives are formed purely in response to the tax on gross receipts.

Market competition absent the tax would push firms to integrate to a level that maximizes economic efficiency. Gross receipts taxes encourage firms to make inefficient decisions if the costs of the inefficiency are made up for by the savings made by avoiding the tax.[47] While this is a beneficial move for firms, the loss of efficiency lessens economic output and real wages over time.

Firms will also consider insourcing functions that they would otherwise outsource absent a gross receipts tax. Businesses outsourcing services, such as payroll or human resources, may bear part of the incidence of the tax if it is forward-shifted onto the business in the form of higher prices.[48] The higher prices would push firms to consider greater insourcing of these services on the margin. Smaller firms may have greater difficulty insourcing, which results in those firms experiencing above-average tax exposure under a gross receipts tax.[49]

Consumer and Labor Impacts

Gross receipts taxes do not only impact business owners and shareholders. Consumers and workers also bear the tax incidence, in the form of higher prices and lower wages.

Tax pyramiding causes prices to increase for consumers, which is the culmination of continual forward-shifting of the tax burden through each stage of production.[50] Consumers will respond to increased prices by adjusting their consumption behavior, impacting businesses and lowering the benefits consumers would have received from their purchases absent the tax. Price increases for consumer goods would vary depending on the amount of tax pyramiding in each industry—goods coming from industries with longer production chains would likely realize higher price increases.[51]

Price increases resulting from a gross receipts tax are regressive. Consumers with lower incomes are affected more when prices rise, as these consumers spend more of their household incomes on goods subject to higher prices.[52] According to Oregon’s Legislative Revenue Office, for example, the proposed gross receipts tax of 2.5 percent in Oregon in 2016 would have decreased after-tax household incomes for households making less than $48,000 by 0.9 percent, while households making more than $206,000 would only see a 0.4 percent decrease in their after-tax income.[53]

Those skeptical of prices increasing under a gross receipts tax have pointed to a survey suggesting that there is no relationship between prices and corporate taxes.[54] Evaluating this empirically is challenging, however—there is no justification for a particular mix of goods selected in such a survey, and cross-state comparisons may fail to account for price differences stemming from different sales tax rates.[55] The survey focuses on pricing by national retailers for name-brand staple goods, which are often subject to national pricing strategies to eliminate price differences across retailers and states.[56]

Economists studying gross receipts taxes agree that tax pyramiding results in higher prices for consumers, despite what a limited survey of name-brand products may find when visiting national retailers.[57] For example, a study of pyramiding effects from retail sales taxes found that prices rise by the amount of the tax on about half of the commodities the authors examined, while the other half saw prices increases greater than the statutory rate.[58]

If firms cannot shift the incidence of a gross receipts tax by raising prices on purchasers down the production chain or on consumers, they may respond to the tax by reducing wages for the firm’s workers, eliminating jobs outright, or slowing the pace of job hiring that would have happened if the tax were not levied. Just as price increases are unequally distributed across different industries and goods, wage decreases, and job losses, are distributed disproportionately.

Oregon’s 2016 proposal to levy a 2.5 percent gross receipts tax is illustrative: estimates from Oregon’s Legislative Revenue Office projected a net loss of 38,200 jobs between 2017 and 2022 if the tax were adopted.[59] The job losses were expected to come disproportionately from a few industries, such as retail trade, wholesale trade, and healthcare services.[60] These are also the industries that are most vulnerable to tax pyramiding, as firms in those industries typically have high volumes and low margins.

Transparency Problems

Gross receipts taxes violate the tax policy principle of transparency. Transparent taxes provide those bearing the tax a clear picture of their tax burden. Tax pyramiding renders gross receipts taxes opaque to firms and consumers, as the tax is embedded within the market price of goods and services those stakeholders acquire.

The effective tax rates imposed by gross receipts taxes are only somewhat dictated by the statutory rates, with the difference determined by industry-specific lengths of production and the amount of tax forward-shifted onto producers down the production chain and onto consumers.[61] This problem is not merely the result of poor tax design but is a feature of the way gross receipts taxes work. Firms are unable to separate the tax out from the other costs of production, leaving both firms and consumers unaware of their total tax burden. Economist Justin Ross argues that gross receipts taxes may be one of the least transparent taxes states may levy.[62]

Tax Complexity

Attempts to rectify the economic problems created by gross receipts taxes lead to complexity for taxpayers. States tend to create different rates across industries to account for their different average lengths of production. They may also modify the tax base to accommodate for production inputs. While this helps mitigate some of the tax pyramiding effects, it does so by increasing complexity in the tax code and introducing the temptation for industries to lobby for a preferential tax rate. This undercuts one of the primary motivations for levying a gross receipts tax, which is that the tax is simple to administer and calculate.

States design their gross receipts taxes using the same starting criteria for their tax base—any transaction made by a business that generates gross revenue for the firm. This includes transactions between businesses and with final consumers. Some states modify the tax further. For example, Texas defines its Margin Tax base as either:

- “Total revenue minus cost of goods sold; or

- Total revenue minus wages (limited to $300,000 per person) and benefits; or

- 70% of total revenue.”[63]

While excluding business inputs from the tax base avoids a significant portion of tax pyramiding, the tax is difficult to navigate. “Cost of goods sold” does not conform to the federal tax code, and excludes selling costs, services, distribution costs, advertising, taxes, and compensation.[64] This added complexity has created significant compliance costs for small businesses in the state.[65] Instead of producing a gross receipts tax without the economic downside, Texas created a “badly designed business profits tax…combin[ing] all the problems of minimum income taxation in general—excess compliance and administrative cost, penalization of the unsuccessful business, undesirable incentive impacts, doubtful equity basis—with those of taxation according to gross receipts.”[66] In addition to added complexity, Texas has not captured stable revenue from the Margin Tax, as revenue shortfalls have become a regular problem.[67] This should be a lesson for states considering a gross receipts tax with the expectation that the tax will be a stable source of revenue.

States that set different gross receipts tax rates by industry encourage lobbying by industries for preferential treatment. Before Indiana repealed its gross receipts tax in 2002, the tax structure was plagued with many rate reductions, increases in deductions, and other preferences on behalf of favored industries.[68] This amplified the economic distortions created by the tax and added complexity to firms working in more than one industry. Upon repeal, Indiana moved “from an antiquated tax toward a simpler, more transparent structure [that] allowed the state to remove barriers and thereby raise capacity for firms and individuals to compete on a level playing field.”[69]

Washington State provides narrow exemptions from its B&O tax in order to relieve low-margins firms from dealing with a disproportionate tax burden. While this may help lessen some of the tax pyramiding effects and equalize effective rates, there remains a trade-off that policymakers must confront when lessening burdens for industries with lower profit margins and longer production chains.[70] Lesser burdens for those industries raise tax complexity and incentives to lobby for economically unproductive and base-eroding carveouts.

States may choose to design their gross receipts taxes based on the experience of other states. This may not lead to good results, despite the good intentions of policymakers. In 2015, Nevada designed the industry codes used for its Commerce Tax based on a 2011 study of Texas’ Margin Tax, an arbitrary selection which impacted tax burdens for firms in the state.[71] Firms sought to be classified in industries exposed to lower gross receipts tax rates, at the expense of economic efficiency. This also invited legal disputes over how firms should be classified, creating more complexity and uncertainty in the tax code.

Efforts to alleviate the problems with gross receipts taxes introduce tax complexity for businesses and cronyism into tax policy decisions. Often, this results in complex, economically costly taxes that do not achieve the very goals set by policymakers: namely, a simple, stable source of tax revenue.

Reforming Extant Taxes on Gross Receipts

States enacting gross receipts taxes are doing so in response to reasonable concerns about revenue stability and, in some cases, structural budget gaps. Thankfully, there are alternatives to the economic damage wrought by taxing gross receipts.

One tool for policymakers to consider is sales tax base broadening. As of 2017, the median state sales tax base is only 23 percent of personal income, when the ideal should include all final personal consumption.[72] State sales taxes are no more volatile than gross receipts taxes, and when properly structured avoid problems like tax pyramiding, tax complexity, and economic harm wrought on firms, consumers, and workers.

The biggest single reform states can make to reduce the costs associated with gross receipts taxes is to eliminate tax liabilities on business-to-business transactions, either through an exemption or a credit applied to them. This would functionally revert the gross receipts tax to a sales tax, which taxes the value of a good or service only once.[73] The economic distortions and lack of transparency created by tax pyramiding would be eliminated.

Replacing revenue from a repealed or proposed gross receipts tax goes beyond merely finding another type of tax to use. States may lean on a gross receipts tax to paper over bigger problems with a tax system or structural budget problem. The right approach is to engage in a broader program of reform, and not to rely on an economically damaging and outdated form of taxation to resolve broader problems.

Policymakers are beginning to recognize the costs associated with gross receipts taxes. In 2015, the Texas legislature lowered Margin Tax rates and added that “it is the intent of the legislature to promote economic growth by repealing the franchise tax.”[74] Despite several attempts to implement a gross receipts tax in Oregon, one proposal failed at the ballot box and the legislature failed to enact one due to lack of support in the chamber.[75] Over the past two years, proposals in Louisiana, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Wyoming failed to get off the ground after policymakers reconsidered their options and saw the problems associated with implementing a gross receipts tax.

Reforming existing gross receipts taxes does not require states to give up on stable sources of revenue, even in the interim. States could use a revenue trigger to help phase in revenue-raising reforms to offset the lost revenue from an eliminated gross receipts tax. Revenue triggers were used as part of broader reform efforts in Iowa and Missouri in 2018 and could be put to good use for states eliminating their gross receipts taxes.[76]

Conclusion

The current debates states are having over gross receipts taxation are not new. In 1925, the economist Edwin Seligman argued that “[t]axes on output or gross receipts which make no allowance for the expenses constitute a rough and ready system, suitable only for the more primitive stages of economic life.”[77] The generation of policymakers succeeding Seligman came to the same conclusion, finding that gross receipts taxes served no place in a modern tax system. It may take time for lawmakers to once again make that discovery.

States can realize greater revenue stability and structurally sound budgets if they rely on principles of sound tax policy and not by adopting a tax that violates the tax principles of neutrality, simplicity, and transparency. Jurisdictions should resist the allure of gross receipts taxes and instead reform their broader tax systems to achieve their goals.

The economic costs of gross receipts taxes are pernicious, as these costs exist alongside a functional appeal that obscures them. While problems like tax pyramiding may appear abstract, they represent real costs borne onto firms, entrepreneurs, workers, and consumers. Policymakers should consider alternatives that meet their objectives while preserving the livelihoods, jobs, and incomes of their constituents.

Notes

[1] John L. Mikesell, “Gross Receipts Taxes in State Government Finances: A Review of Their History and Performance,” Tax Foundation and Council on State Taxation, January 2007, 3, https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/bp53.pdf.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Andrew Chamberlain and Patrick Fleenor, “Tax Pyramiding; The Economic Consequences of Gross Receipts Taxes,” Tax Foundation, December 2006, 2, https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/sr147.pdf.

[4] Ibid.

[5] John F. Due and John L. Mikesell, Sales Taxation: State and Local Structure and Administration (Washington, D.C: Urban Institute Press, 1994), 55.

[6] Andrew Chamberlain and Patrick Fleenor, “Tax Pyramiding; The Economic Consequences of Gross Receipts Taxes.”

[7] Nicole Kaeding and Erica York, “Gross Receipts Taxes: Lessons from Previous State Experiences,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 10, 2016, 3, https://taxfoundation.org/gross-receipts-taxes-state-experiences/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Jared Walczak, “Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax: A Reappraisal,” Tax Foundation, September 2017, https://files.taxfoundation.org/20170922161821/Tax-Foundation-CAT.pdf.

[10] Jared Walczak, “Why Does Missouri Want a Gross Receipts Tax?” Tax Foundation, Sept. 26, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/missouri-want-gross-receipts-tax/.

[11] Jared Walczak, “West Virginia Becomes the Latest State to Contemplate a Gross Receipts Tax,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 14, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/west-virginia-becomes-latest-state-contemplate-gross-receipts-tax/.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Jared Walczak, “Nevada Approves Commerce Tax, A New Tax on Business Gross Receipts,” Tax Foundation, June 8, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/nevada-approves-commerce-tax-new-tax-business-gross-receipts/.

[16] Nicole Kaeding, “The Return of Gross Receipts Taxes,” Tax Foundation, March 28, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/return-gross-receipts-taxes/; and Jared Walczak, “Trends in State Tax Policy, 2018,” Tax Foundation, December 2017, 5, https://files.taxfoundation.org/20171213151239/Tax-Foundation-FF568.pdf.

[17] John L. Mikesell, “Gross Receipts Taxes in State Government Finances: A Review of Their History and Performance,” 4-6.

[18] Ohio Department of Taxation, “2015 Annual Report”: 38-39. http://www.tax.ohio.gov/Portals/0/communications/publications/annual_reports/2015_Annual_Report/2015_AR.pdf.

[19] Some business inputs are legally exempt from a sales tax but may be inadvertently taxed if the input is also a consumer good. For example, a restaurant owner may pay sales tax on tables and chairs if the owner does not provide a sales tax exemption certificate to the seller.

[20] Nicole Kaeding, “Sales Tax Base Broadening: Right-Sizing a State Sales Tax,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 24, 2017, https://www.taxfoundation.org/sales-tax-base-broadening/.

[21]Jared Walczak, “Nevada Approves Commerce Tax, A New Tax on Business Gross Receipts,” Tax Foundation, June 8, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/nevada-approves-commerce-tax-new-tax-business-gross-receipts.

[22] Scott Drenkard, “Businesses Love Texas, Except this One Tax that Holds the State Back,” Tax Foundation blog, Jan. 8, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/businesses-love-texas-except-one-tax-holds-state-back/.

[23] For example, Pennsylvania levies a gross receipts tax on telecommunications, energy, and certain transportation firms, while Florida taxes gross receipts for utility services. See Pennsylvania Department of Revenue, “The Tax Compendium, March 2017,” https://www.revenue.pa.gov/GeneralTaxInformation/News%20and%20Statistics/ReportsStats/TaxCompendium/Documents/2017_tax_compendium.pdf; Florida Department of Revenue, “Florida Gross Receipts Tax on Utility Services,” http://floridarevenue.com/taxes/taxesfees/Pages/grt_utility.aspx.

[24]Andrew Chamberlain and Patrick Fleenor, “Tax Pyramiding; The Economic Consequences of Gross Receipts Taxes,” 1.

[25] Missouri Governor’s Committee on Simple, Fair, and Low Taxes, “Tax Policy and Tax Credit Reform: Recommendations to Make Missouri a Best-In-Class State,” June 30, 2017, 23, http://themissouritimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/TC-Report-Working-Draft-06192.pdf.

[26] John Mikesell, “Gross Receipts Taxes in State Government Finances: A Review of Their History and Performance,” 8-9.

[27] In many cases, these taxes have a tax base greater than the gross domestic product of the taxing jurisdiction, as the base includes the final value of a good (measured in GDP) and the value of the transactions leading up to the final product. For example, Washington State’s B&O tax base in 2005 added up to 177 percent of the state gross domestic product. See Ibid, 7.

[28] Jared Walczak, “Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax: A Reappraisal,” 13.

[29] Justin M. Ross, “Gross Receipts Taxes: Theory and Recent Evidence,” Tax Foundation, October 2016, 9-10, https://files.taxfoundation.org/20170403095541/TaxFoundation-FF529.pdf.

[30] Jared Walczak, “Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax: A Reappraisal,” 4.

[31] See generally, Andrew Chamberlain and Patrick Fleenor, “Tax Pyramiding; The Economic Consequences of Gross Receipts Taxes.”

[32] This table assumes that the economic incidence of the tax is fully forward-shifted to the next stage of production for simplicity.

[33] Andrew Chamberlain and Patrick Fleenor, “Tax Pyramiding; The Economic Consequences of Gross Receipts Taxes,” 6.

[34] Robert Lawson, “The Economics of Gross Receipts Taxes: A Case Study of Ohio,” in Adam J. Hoffer and Todd Nesbit, eds., For Your Own Good: Taxes, Paternalism, and Fiscal Discrimination in the Twenty-First Century (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2018), 215-216, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3173790.

[35] Washington State Tax Structure Study Committee, “Tax Alternatives for Washington State: A Report to the Legislature,” Volumes 1 & 2, November 2002, https://dor.wa.gov/reports/tax-structure-final-report.

[36] Jared Walczak, “Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax: A Reappraisal,” 10.

[37] Michael Smart and Richard M. Bird, “The Economic Incidence of Replacing a Retail Sales Tax with a Value-Added Tax: Evidence from Canadian Experience,” Canadian Public Policy 35, no. 1, March 2009, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40213402.

[38] John L. Mikesell, “Gross Receipts Taxes in State Government Finances: A Review of Their History and Performance,” 7.

[39] Daniel R. Mullins, Andrew D. Phillips, and Daniel J. Sufranski, “Analysis of Proposed Changes to Select Ohio Taxes Included in the Ohio Executive Budget and Ohio House Bill Number 64,” State Tax Research Institute and EY Quantitative Economics and Statistics Practice, March 2015, 20, https://cost.org/globalassets/cost/stri/studies-and-reports/analysis-of-proposed-changes-to-select-ohio-taxes-included-in-the-ohio-executive-budget.pdf.

[40] Jared Walczak, “Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax: A Reappraisal,” 13.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Andrew Chamberlain and Patrick Fleenor, “Tax Pyramiding; The Economic Consequences of Gross Receipts Taxes,” 7.

[43]Jared Walczak, “West Virginia Becomes the Latest State to Contemplate a Gross Receipts Tax.”

[44] Ibid.

[45] John L. Mikesell, “Gross Receipts Taxes in State Government Finances: A Review of Their History and Performance,” 11.

[46] Andrew Chamberlain and Patrick Fleenor, “Tax Pyramiding; The Economic Consequences of Gross Receipts Taxes,” 6.

[47] Ibid, 8.

[48] John L. Mikesell, “Gross Receipts Taxes in State Government Finances: A Review of Their History and Performance,” 9.

[49] Jared Walczak, “Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax: A Reappraisal,” 5.

[50] Nicole Kaeding, “Oregon’s Gross Receipts Tax Proposal Would Increase Consumer Prices,” Tax Foundation, July 18, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/oregons-gross-receipts-tax-proposal-would-increase-consumer-prices.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Nicole Kaeding, “Oregon’s Gross Receipts Tax Would Be Regressive,” Tax Foundation, July 19, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/oregon-s-gross-receipts-tax-would-be-regressive.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Shamus Lynsky and Daniel Morris, “Side-by-Side Shopping Cart Study: State Corporate Taxes Do Not Drive State Consumer Prices,” Oregon Consumer League, http://oregonconsumerleague.org/wp-content/uploads/Side-by-Side-Shopping-Cart-Study.pdf.

[55] Nicole Kaeding, “Yes, Really. Measure 97 Would Raise Prices,” Tax Foundation, July 28, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/yes-really-initiative-petition-28-would-raise-prices/.

[56] Ibid.

[57] John L. Mikesell, “Gross Receipts Taxes in State Government Finances: A Review of Their History and Performance,” 3.

[58] Timothy J. Besley and Harvey S. Rosen, “Sales Taxes and Prices: An Empirical Analysis,” National Tax Journal 52, no. 2, June 1999, 157-178, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41789387.

[59] Nicole Kaeding, “Oregon’s Gross Receipts Tax Proposal Would Hurt Job Creation,” Tax Foundation, July 19, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/oregon-s-gross-receipts-tax-proposal-would-hurt-job-creation.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Andrew Chamberlain and Patrick Fleenor, “Tax Pyramiding; The Economic Consequences of Gross Receipts Taxes,” 7.

[62] Justin M. Ross, “A Primer on State and Local Tax Policy: Trade-Offs Among Tax Instruments,” Mercatus Center Research Paper, Feb. 25, 2014, 19, https://www.mercatus.org/publication/primer-state-and-local-tax-policy-trade-offs-among-tax-instruments.

[63] 17 Tex. Tax Code § 171

[64]Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “Texas Margin Tax Experiment Failing Due to Collection Shortfalls, Perceived Unfairness for Taxing Unprofitable and Small Businesses, and Confusing Rules,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 17, 2011, https://taxfoundation.org/texas-margin-tax-experiment-failing-due-collection-shortfalls-perceived-unfairness-taxing/.

[65] Don Bolding, “Texas Legislature lifts some ‘margin tax’ burden off owners,” Killeen (Texas) Daily Herald, July 12, 2009, http://kdhnews.com/business/texas-legislature-lifts-some-margin-tax-burden-off-owners/article_82abab24-45df-5b52-95da-60af183399a4.html?mode=story.

[66] John L. Mikesell, “Gross Receipts Taxes in State Government Finances: A Review of Their History and Performance,” 4 n.6.

[67] Scott Drenkard, “The Texas Margin Tax: A Failed Experiment,” Tax Foundation, January 2015, 2-3, https://files.taxfoundation.org/20170801132909/TaxFoundation-SR226.pdf.

[68] Nicole Kaeding and Erica York, “Gross Receipts Taxes: Lessons from Previous State Experiences,” 3.

[69] Ibid, 6.

[70] Jared Walczak, “Washington’s Business Tax Structure,” Written Testimony for the Washington House Tax Structure Working Group, Tax Foundation, July 23, 2018, 2, https://files.taxfoundation.org/20180723164020/Tax-Foundation-Testimony-WA-House-Tax-Structure-Work-Group.pdf.

[71] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, Liz Malm, and Jared Walczak, “The 13 Million Percent Tax: Nevada Considers Complex, Arbitrary BLF Proposal,” Tax Foundation, March 2015, 12, https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/TaxFoundation_FF459.pdf.

[72] See generally, Nicole Kaeding, “Sales Tax Base Broadening: Right-Sizing a State Sales Tax.”

[73] Thomas F. Pogue, “The Gross Receipts Tax: A New Approach to Business Taxation?” National Tax Journal, 60, no. 4 (December 2007), 817, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41790620.

[74] Scott Drenkard, “Businesses Love Texas, Except this One Tax that Holds the State Back,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 8, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/businesses-love-texas-except-one-tax-holds-state-back/.

[75] Nicole Kaeding, “Oregon’s Quest for a Gross Receipts Tax Ends…For Now,” Tax Foundation, June 22, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/oregons-quest-gross-receipts-tax-endsfor-now/.

[76] Jared Walczak, “Tax Trends Heading into 2019,” Tax Foundation, December 2018, 14-15, https://files.taxfoundation.org/20181220135128/Tax-Trends-Heading-Into-2019-FF-628.pdf.

[77] Edwin R.A. Seligman, Studies in Public Finance (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1925), 134-135.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Resisting the Allure of Gross Receipts Taxes: An Assessment of Their Costs and Consequences

TAXTIMEKC

TAXTIMEKC