by r Hampton | Jan 23, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – States Should be Wary of ITEP Marijuana Tax Policy

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy is out today with a report recommending how states should approach taxing legalized marijuana. It’s a topic we’ve written about extensively, and based on that research, we have some concerns with the report’s suggestion that states tax marijuana based on the weight of the amount sold rather than the retail sales price.

ITEP argues that weight-based taxes on the grower and/or processor would be less prone to evasion and easier to collect than price-based taxes at the retail level. I disagree. Washington moved away from taxing growers and processors because they found retail collection simpler, prevented an accidental hefty federal tax on processors and growers, and removed an unintentional incentive for vertical integration.

Not all marijuana is the same, either: more potent “premium” strains weigh the same as other strains. Price, however, is an effective proxy for potency.

ITEP wants to do this because it says tax revenues will fall otherwise. There is no evidence for that. It is true that marijuana wholesale prices have fallen, but that is a feature, not a bug, of legalization. It allows the legal market to compete effectively with the black market, as one of the goals of the legalization is to wipe out that black market.

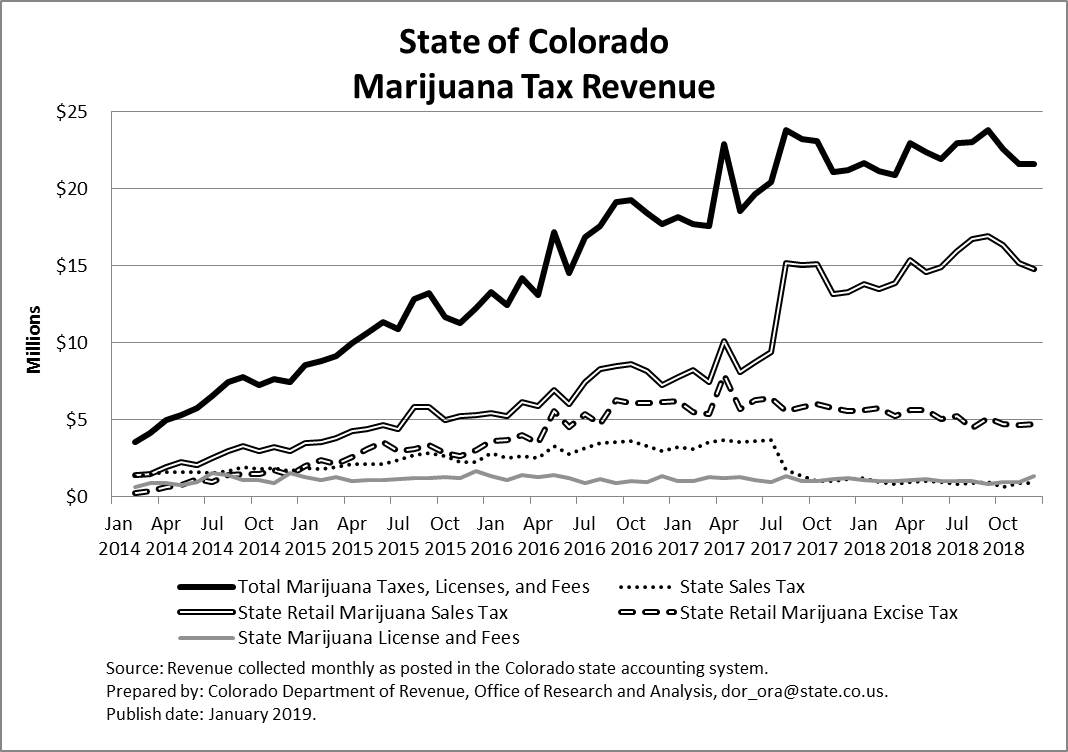

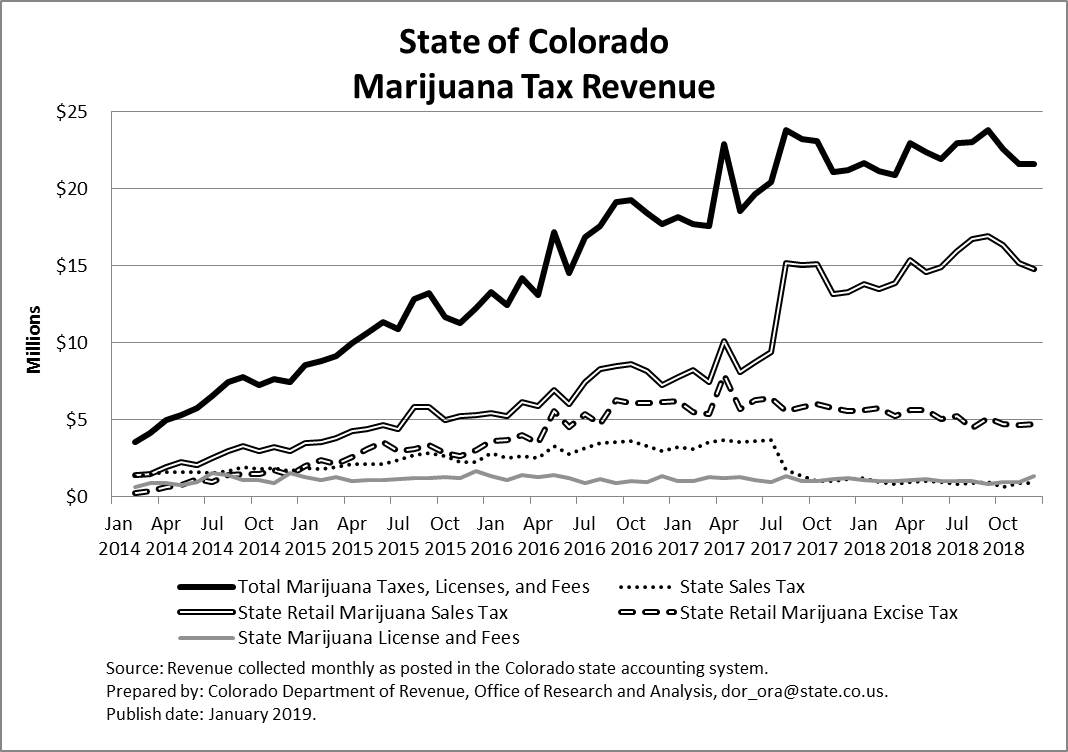

The drop in wholesale prices has occurred at the same time as soaring state marijuana tax revenues. Colorado’s revenue, for instance, during this period of “collapsing prices”:

If revenue growth is not about to collapse under a price-based tax, that undermines ITEP’s main argument. On page 22-24, they acknowledge there’s no sign of an imminent collapse in tax revenues but still predict it anyways: “While there appears to be some leveling-off of revenue growth in states where cannabis taxation has been underway for several years, there are no guarantees that future cannabis tax revenues—particularly those raised by price-based taxes—will plateau for long.” (In an earlier version of this post, I wrote they hadn’t acknowledged marijuana revenue growth in states that have legalized; I was wrong and have corrected this paragraph accordingly.) There is zero evidence state marijuana tax revenues are about to collapse; my reading is that there will be continued growth until it stabilizes at a mature market level and the growth rate (and state tax revenue) plateaus.

These reasons are why contrary to ITEP’s recommendation, states that have legalized marijuana so far primarily rely on price-based taxes.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – States Should be Wary of ITEP Marijuana Tax Policy

by r Hampton | Jan 23, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Spotify Mixes Up Tax Notices to D.C. and Iowa Subscribers

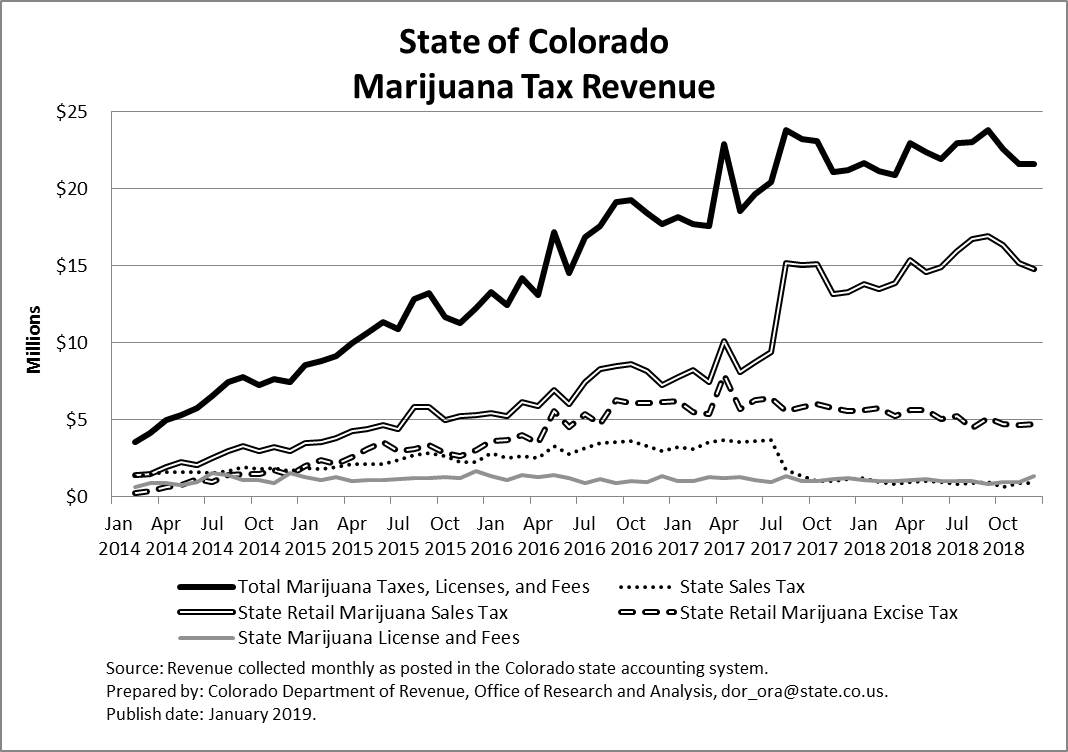

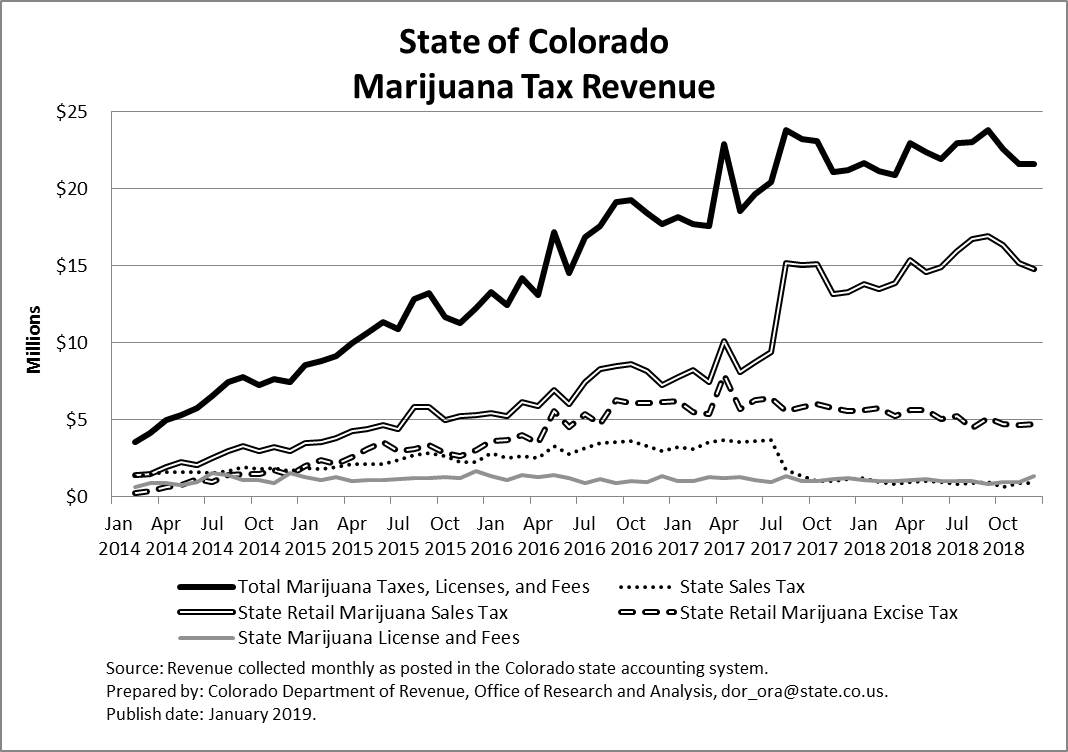

Digital music service Spotify surprised many of its subscribers yesterday, with those in D.C. learning they now had to pay Iowa’s sales tax on their subscription:

Iowa subscribers got a similar message but reversed, informing them they’ll have to pay D.C. sales tax.

Not to worry. Late in the day, Spotify e-mailed again to say it had been “a mix-up on our part” and clarifying that Iowa subscribers will pay Iowa sales tax and D.C. subscribers will pay D.C. sales tax. (Iowa subscribers, however, might have preferred paying D.C.’s 6 percent sales tax instead of their 7 percent sales tax, which is the rate in most cities.)

It does highlight an interesting issue: With Spotify headquartered in New York, a data center in Virginia, and subscribers presumably everywhere, which state properly gets to put its sales tax on Spotify’s sales? The general practice is to tax based on billing address, but that’s not a mandated rule. States can deviate from it, although a state taxing someone with no connection to the state would raise constitutional issues. A bipartisan federal bill to set billing address as the default tax rule for all states, the Digital Goods and Services Tax Fairness Act, remains pending in Congress.

Why Iowa and D.C.? Iowa last year passed a tax overhaul that reduced individual and business tax rates, eliminated tax deductions and credits, and removed exceptions to the sales tax base. Starting this year, their sales tax now applies to digital goods, ridesharing, and subscription services, including Spotify. D.C. passed legislation at the end of 2018 imposing sales tax on online sales above a certain threshold and applying the sales tax to digital goods and services. Before, some were exempt and some (video streaming) were subject to a 10 percent utility gross receipts tax. Now all just pay the 6 percent sales tax.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Spotify Mixes Up Tax Notices to D.C. and Iowa Subscribers

by r Hampton | Jan 21, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – New Swedish Coalition Government Proposes Sweeping Tax Cut Plan

Sweden has been much in the news recently following the comments by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez that her proposal to boost the top income tax rate in the U.S. to 70 percent is based on the tax policies in the Scandinavian nation.

According to a recent Reuters news report, it would seem that Sweden is trying to reverse its reputation for high taxes. After four months of attempting to build a coalition government, Reuters reports that “Prime Minister Stefan Lofven’s Social Democrats have agreed to a draft policy deal with the Centre, Liberal and Green parties” that “would cut taxes for wage-earners and companies.”

Below are key reforms outlined in the draft agreement according to Reuters.

- “A broad tax reform is to be implemented that would lower taxes on income and enterprise. The reform includes an agreement to cut marginal tax rates and raise the threshold at which people start to pay the higher rate of tax.

- “While income taxes are lowered, environmental taxes will be increased by at least 15 billion Swedish crowns ($1.66 billion) to help offset the loss of revenue.

- “Taxes for retirees to be lowered in 2020 and pensions raised for those on low and medium incomes.

- “Corporate taxes, especially for small and medium-sized companies, are to be made more [favorable]. Social contribution fees paid by companies are to be lowered while tax breaks for household services are to be extended.

- “[Labor] regulations are to be adapted in a way that would allow companies greater leeway regarding whom to lay off in case of redundancies.

- “Taxes on stock options will be lowered to make Sweden more attractive for start-ups in an international perspective.

- “Interest rate payments on deferred taxes on housing sales will be abolished.”

While the debate in the U.S. has focused on Sweden’s top marginal personal income tax rate of 57 percent, few have mentioned that Sweden has one of the lowest corporate income tax rates in Europe, at 22 percent. Moreover, Sweden abolished its estate and inheritance tax a few years ago and, unlike other European countries, it does not have a wealth tax.

Because of Sweden’s high-tax reputation, many are surprised that the country ranks 7th best on the Tax Foundation’s International Tax Competitiveness Index. The Index ranks OECD countries on how they raise taxes, not on how much they raise. Tax systems are judged on how little they distort economic behavior (tax neutrality) and how low their rates are relative to other countries (their competitiveness). Some of Sweden’s rates are high, such as the 25 percent Value-Added Tax, but they are levied on a broad base with a minimal amount of exemptions or carveouts for certain industries or products.

The tax cuts proposed by the new coalition government could well make Sweden even more competitive, despite how many Americans inaccurately view it as a socialist paradise.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – New Swedish Coalition Government Proposes Sweeping Tax Cut Plan

by r Hampton | Jan 19, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Sorry, Washington State: Capital Gains Taxes are Still Income Taxes—But There’s a Better Way

Every state has its traditions, and in Washington, you can mark the dawn of a new year by the inevitable attempt to tax capital gains—and the insistence that, despite appearances, it’s not a tax on income.

On Thursday, Washington Senate Majority Leader Andy Billig (D) went on Inside Olympia to discuss the proposal and to explain why, in his opinion, it does not constitute a tax on income (functionally prohibited by the state constitution), even though in other states and at the federal level, capital gains are taxed under the individual income tax.

Senator Billig observed that “income gets taxed at one level [while] capital gains, at the federal level, gets taxed at another level”—which is true, at least where long-term capital gains are concerned. This, however, is a tax preference within the individual income tax: long-term capital gains receive a lower, preferential rate.

The tax code is full of preferences, old and new. Under the new federal tax law, pass-through business income receives preferential tax treatment, for instance, though this is accomplished through a deduction. For an alternative rate, one might look to the alternative minimum tax (AMT), which uses an entirely different rate schedule than the rest of the individual income tax, but is undeniably still taxing income. Which is why Sen. Billig is correct about this prediction: “Ultimately it’s going to be up to a court to decide.”

At the federal level, short-term capital gains are taxed as ordinary income, while long-term capital gains are taxed at a lower rate. Somewhat ironically, proposals in Washington would exempt short-term capital gains altogether and only tax long-term gains (which receive preferential federal treatment) because the state law would draw from that line of taxpayers’ federal income tax return—another hint, perhaps, that this is clearly an income tax.

But forget hints: consider the difference in how income and excise taxes function, since proponents of a Washington capital gains tax want to call this an excise tax on the privilege of earning capital gains. Excise taxes fall on specific transactions—for instance, the purchase of gasoline or cigarettes—and are typically levied per unit (on volume). For instance, Washington’s gas tax is 49.4 cents a gallon, regardless of the price of gasoline. Occasionally they look more like specific sales taxes, levied on an ad valorem basis, like Washington’s 37 percent excise tax on recreational marijuana.

But in either case, they fall on a specific good or service and—most importantly—they’re based on sales, either in price or volume. That’s not how capital gains taxes work. They’re not levied at a set rate on each financial transaction. Rather, they’re imposed on the net income from investments when that income is realized. There’s no getting around that this is an income tax—just a very narrow one.

Interestingly, in his interview, Sen. Billig observed that “the best tax system is a tax that is wide but not deep, so tax a lot of things, but don’t tax them a lot.” Unfortunately, that’s pretty much the opposite of what can be achieved by a tax on long-term capital gains. It’s a volatile tax on a narrow definition of income, in an area where people often have significant control of when and how they realize that income.

If Washington did adopt a capital gains tax, moreover, one wonders whether state officials would maintain their insistence that it’s an excise tax for purposes of the state and local tax deduction.

When determining federal tax liability, taxpayers can deduct property taxes plus their choice of income or sales taxes, up to a (new) cap of $10,000. In a state like Washington, which forgoes an individual income tax, itemizers go with the sales tax—though, more accurately, most taxpayers use IRS tables that convert their income into a “standard” sales tax figure that can be substituted for actually tracking purchases.

If Washington adopted a capital gains tax, some taxpayers would benefit from deducting their state capital gains tax payments rather than their estimated sales tax payments, but that of course depends on their ability to characterize the tax as an income tax. It’s pretty clear the IRS would allow it—but what would state officials think, given their position that it’s decidedly not an income tax?

Incidentally, that new $10,000 cap also means that the cost of state taxes is now higher. The state and local tax deduction essentially subsidizes state taxes, allowing a portion of the burden to be exported to taxpayers across the country. The cap limits the ability to do that, particularly for high earners. States like New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut have all expressed concern that their high rates on higher-income residents could backfire on them, driving people out of state, now that this federal subsidy has been cut.

Yet Washington policymakers want to impose a particularly high rate tax on capital gains income. That could be a risky move even if the tax didn’t face such an enormous constitutional challenge.

Sen. Billig is right to want a tax code with broad bases and low rates. This is the opposite of that. Instead, legislators might look to broaden the state’s narrow sales tax base, taxing additional services. This would make the tax more stable while also enhancing progressivity, since services are disproportionately consumed by higher-income individuals, and yet are currently exempt—a huge tax break for wealthier Washingtonians that carries very little economic benefit.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Sorry, Washington State: Capital Gains Taxes are Still Income Taxes—But There’s a Better Way

TAXTIMEKC

TAXTIMEKC