by r Hampton | Dec 27, 2018 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Tax Changes Taking Effect January 1, 2019

Champagne will flow, Auld Lang Syne will be sung, resolutions will be made (and soon forgot, and never brought to mind), and, in a handful of states, taxes will change.

There is less January 1st activity than we usually see, but this does not mean 2018 was a quiet year. Rather, state consideration of tax conformity after the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 moved many changes forward, with rate reductions and other adjustments adopted midyear made retroactive to the start of the year. For instance, Idaho, Utah, and Vermont all trimmed income tax rates this year—but made them effective January 1 of 2018, not 2019.[1]

This was also a significant year for ballot measures, but some of the changes approved by the voters will take time to go into effect. Voters approved the legalization and taxation of marijuana in both Michigan and Missouri, but marijuana won’t go on sale in these states on January 1st.[2] Lawmakers and regulators still have work ahead of them before the new regimes go into effect.

Finally, many legislatures postponed at least some elements of their conformity considerations to 2019. In some cases, they didn’t update their conformity statutes at all. In others, states punted on what to do with the new revenue and will have to decide in 2019 whether to return it in the form of tax reform or other tax relief, or whether to add it to the budget baseline.

So while this January 1st will be a little quieter than usual on the tax front, there is no reason to expect anything less than a frenetic pace in the new year. Here are the significant tax changes taking effect on January 1, 2019.

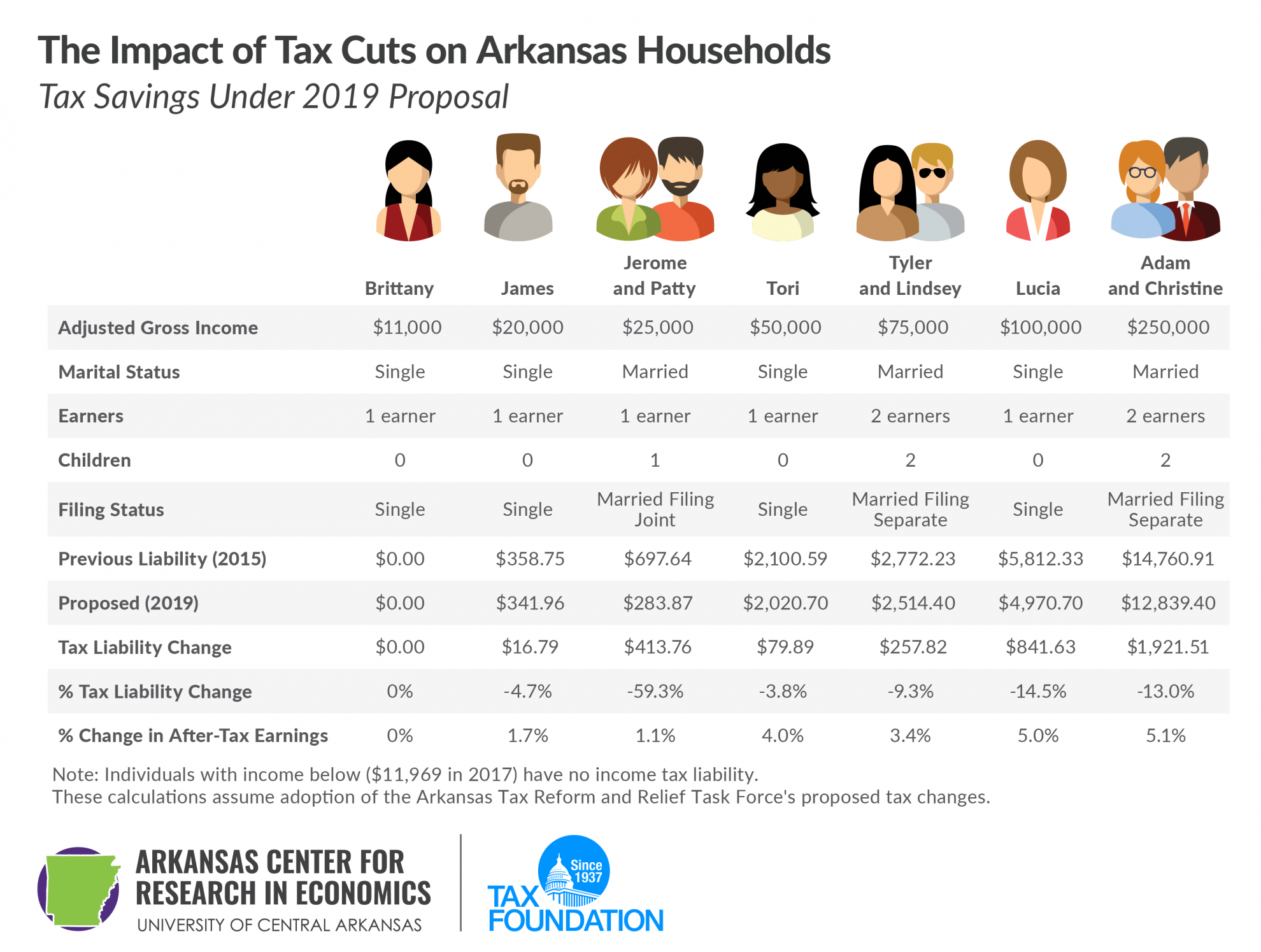

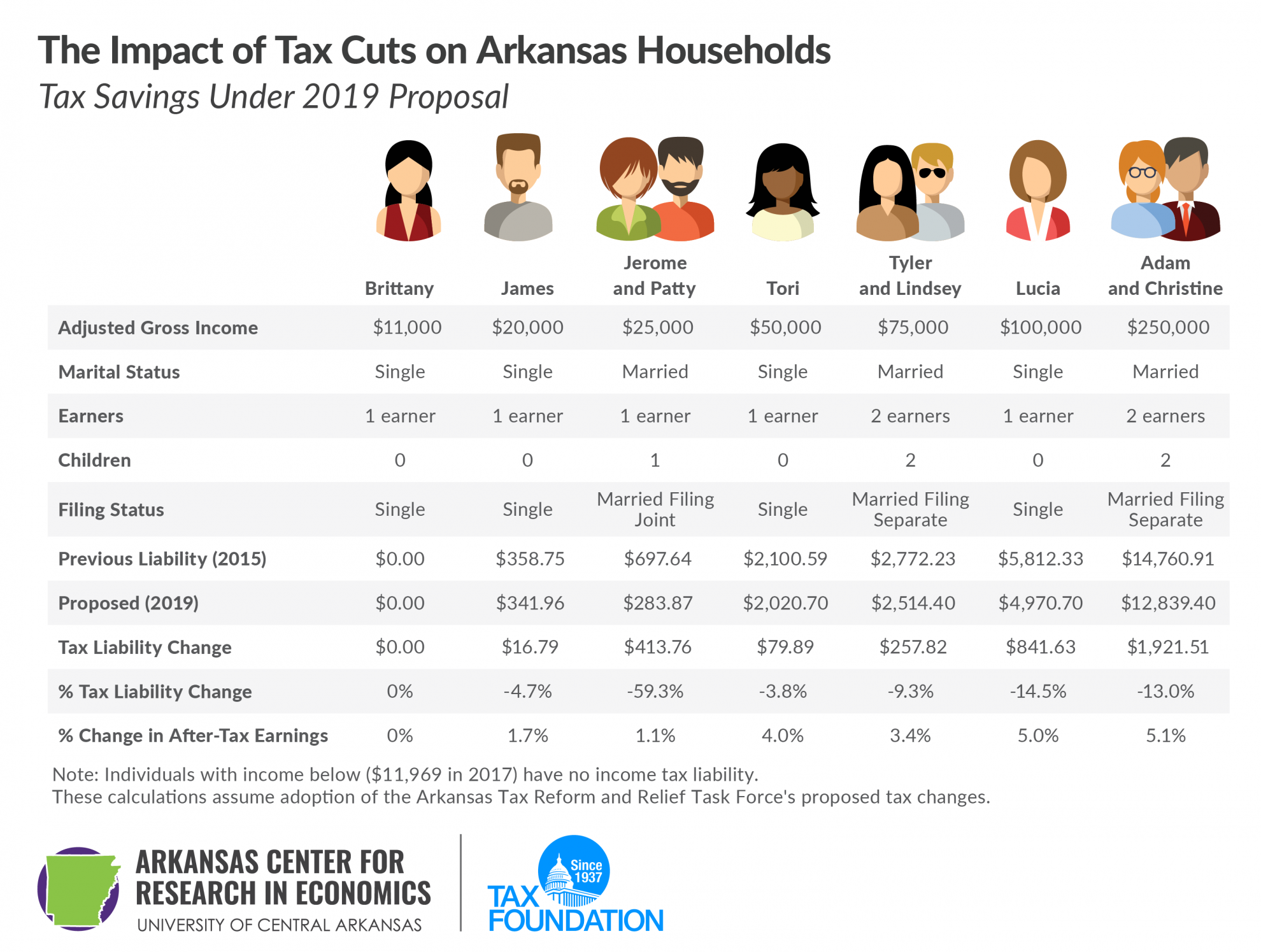

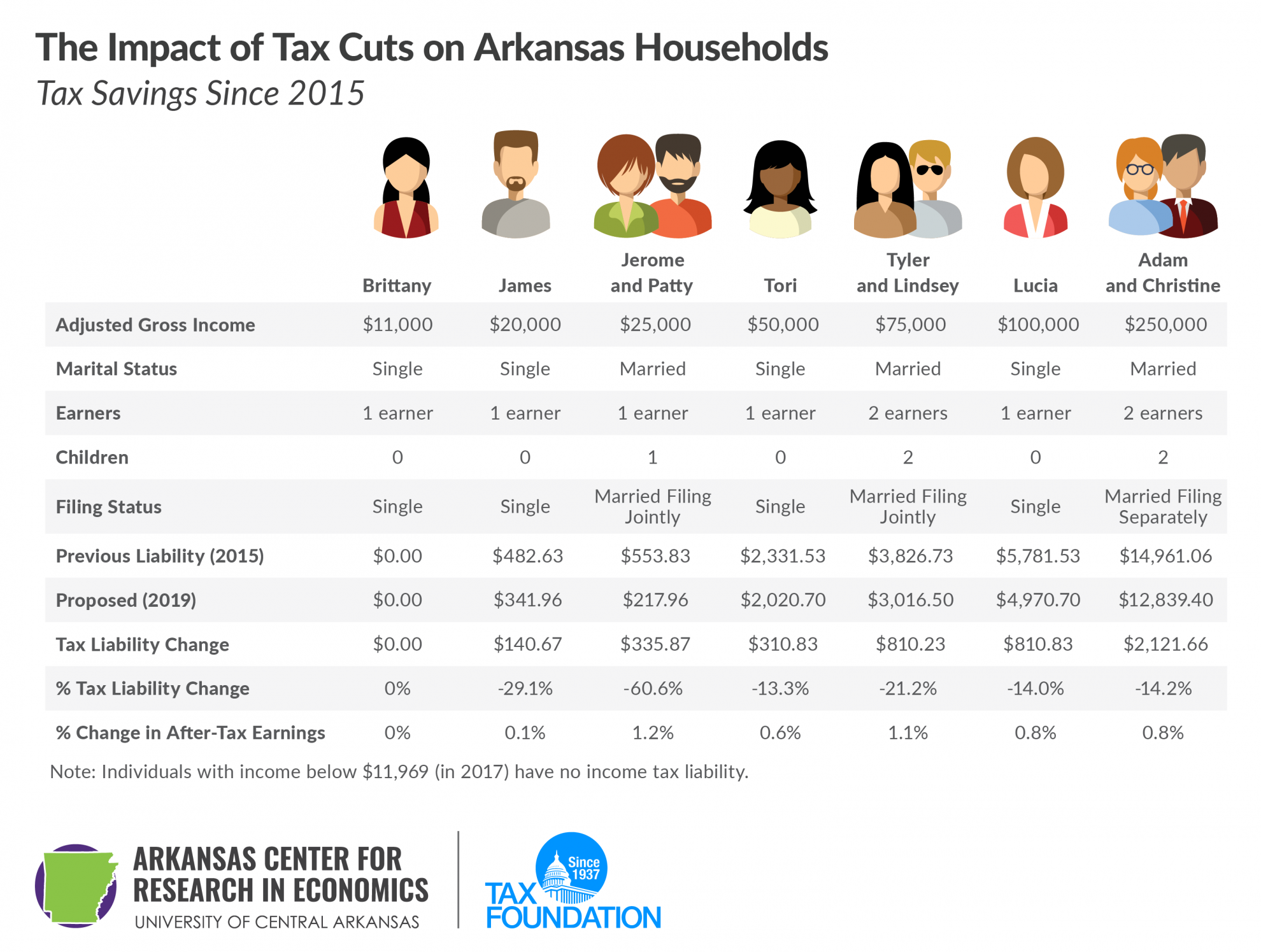

In Arkansas, low-income tax relief legislation goes into effect on January 1st. Arkansas is unique among states inasmuch as it has three entirely different rate schedules depending on total taxable income. As taxpayers’ income rises, they not only face higher marginal rates but also shift into entirely different rate schedules. In the new year, the top rate for the lowest schedule (for income between $12,600 and $20,999) will decline from 4.4 to 3.4 percent, with lower brackets seeing rate reductions as well. The lowest bracket (the first $4,299 of taxable income) of the next rate schedule, for filers earning between $21,000 and $75,000, also sees a rate cut, from 0.9 to 0.75 percent.[3]

|

Note: the exact brackets will change slightly due to Arkansas’s policy of inflation-adjusting its brackets annually. Source: Act 78, Arkansas 2017.

|

| Total Income Under $21,000 |

|

Total Income Between $21,000 and $75,000 |

|

Total Income Above $75,000 |

| Income Bracket |

Tax Rate |

Income Bracket |

Tax Rate |

Income Bracket |

Tax Rate |

Individual Income Tax Rates (2019)

| $0-$4,299 |

0.0% |

|

$0-$4,299 |

0.75% |

|

$0-$4,299 |

0.9% |

| $4,300-$8,399 |

2.0% |

$4,300-$8,399 |

2.5% |

$4,300-$8,399 |

2.5% |

| $8,400-$12,599 |

3.0% |

$8,400-$12,599 |

3.5% |

$8,400-$12,599 |

3.5% |

| $12,600-$20,999 |

3.4% |

$12,600-$20,999 |

4.5% |

$12,600-$20,999 |

4.5% |

| |

$21,000-$35,099 |

5.0% |

$21,000-$35,099 |

6.0% |

| $35,100-$75,000 |

6.0% |

$35,100+ |

6.9% |

In Georgia, both the corporate rate and the top marginal individual income tax rate will decline from 6.0 to 5.75 percent on January 1st to offset additional revenue due to the base-broadening provisions of the TCJA. Because many of those federal provisions are temporary, these state rate reductions have a sunset provision, expiring at the end of 2025 (when individual income tax changes are scheduled to sunset at the federal level).[4]

In Mississippi, a franchise tax phasedown which began in 2018 (with the implementation of a small exemption) continues with a rate reduction, from 2.5 to 2.25 mills, as of January 1, 2019. The tax will slowly phase out through 2028. The amount of federal self-employment taxes individuals can deduct is also slated to rise in 2019.[5]

In Missouri, the first stage of a recently-adopted tax reform package will take effect with the elimination of one bracket of the state’s individual income tax and the reduction of the top rate from 5.9 to 5.4 percent. This will be paired with a phased reduction in the ability of high earners’ ability to claim a deduction for federal taxes paid and a cap on the expansion of the state’s tax preference for pass-through income. Further reform is slated for 2020, when shifting to a unitary apportionment factor (companies currently get their choice of single sales factor or three-factor apportionment; in 2020, nearly all companies will be subject to single sales factor apportionment) will permit a reduction in the corporate rate, from 6.25 to 4.0 percent.[6]

In New Hampshire, the state’s two business taxes will see rate reductions for the second year in a row. Legislation adopted in 2017 phases in reductions of the business profits tax (BPT, the state’s corporate income tax) and the business enterprise tax (BET, a kind of value-added tax). In 2018, the BPT declined from 8.2 to 7.9 percent and the BET from 0.72 to 0.675 percent. On January 1, 2019, the rates decline further, to 7.7 and 0.60 percent respectively.[7]

In North Carolina, the individual income tax rate will decline from 5.499 to 5.25 percent, while the corporate income tax rate will be trimmed from 3.0 to 2.5 percent, the nation’s lowest corporate rate,[8] as the state continues to meet revenue targets. Although no further reductions are currently scheduled, some legislators are already beginning to contemplate repealing the tax outright in coming years. Although North Carolina’s corporate income tax is now extremely competitive, the state does still have a large capital stock tax on the books.

And Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Nebraska, and Utah are all scheduled to begin collecting sales taxes from remote sellers as of January 1, joining 20 states which already do so.[9]

The coming year promises to be an active one in the realm of tax policy. With issues like the taxation of marijuana and sports betting coming to the fore and the taxation of remote sales increasingly within states’ reach, along with the ongoing ripple effects of federal tax reform, January’s rate changes are only the beginning.

Notes

[1] Vermont Acts & Resolves, Act 11, 2018 Special Sess.; Utah Code Annotated § 59-10-104; Jared Walczak, “Two States Cut Taxes Due to Federal Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, March 19, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/two-states-cut-taxes-due-federal-tax-reform.

[2] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, Jared Walczak, and Katherine Loughead, “Results of 2018 State and Local Tax Ballot Initiatives,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 6, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/2018-state-tax-ballot-results/.

[3] Nicole Kaeding, “Tax Cuts Signed in Arkansas,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 2, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-cuts-signed-arkansas/.

[4] Georgia House Bill No. 918, Georgia 154th General Assembly, 2017-2018 Reg. Sess.

[5] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “Mississippi Approves Franchise Tax Phasedown, Income Tax Cut,” Tax Foundation, May 16, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/mississippi-approves-franchise-tax-phasedown-income-tax-cut/.

[6] Jared Walczak, “Missouri Governor Set to Sign Income Tax Cuts,” Tax Foundation, July 11, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/missouri-governor-set-sign-income-tax-cuts/.

[7] New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration, “Business Tax Data,” https://www.revenue.nh.gov/transparency/business-tax.htm.

[8] North Carolina Session Law 2017-57.

[9] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, Hannah Walker, and Denise Garbe, “Post-Wayfair Options for States,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 29, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/post-wayfair-options-for-states/.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Tax Changes Taking Effect January 1, 2019

by r Hampton | Dec 19, 2018 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Tax Trends Heading Into 2019

Key Findings

- State tax changes are not made in a vacuum. States often adopt policies after watching peers address similar issues. Several notable trends in tax policy have emerged across states in recent years, and policymakers can benefit from taking note of these developments.

- The enactment of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) expanded many states’ tax bases and drove deliberations on tax conformity. At year’s end, only five states conform to an older version of the federal tax code, though many have yet to resolve issues raised by their tax conformity regimes.

- Several states experimented with mechanisms to allow their high-income taxpayers to avoid the new cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, efforts cast into doubt–though not entirely ended–by draft U.S. Treasury regulations.

- Three states and the District of Columbia cut corporate taxes in 2018, with rate reductions pending in two other states. Reductions in other taxes on capital are ongoing as well, with Mississippi beginning the phaseout of its capital stock tax.

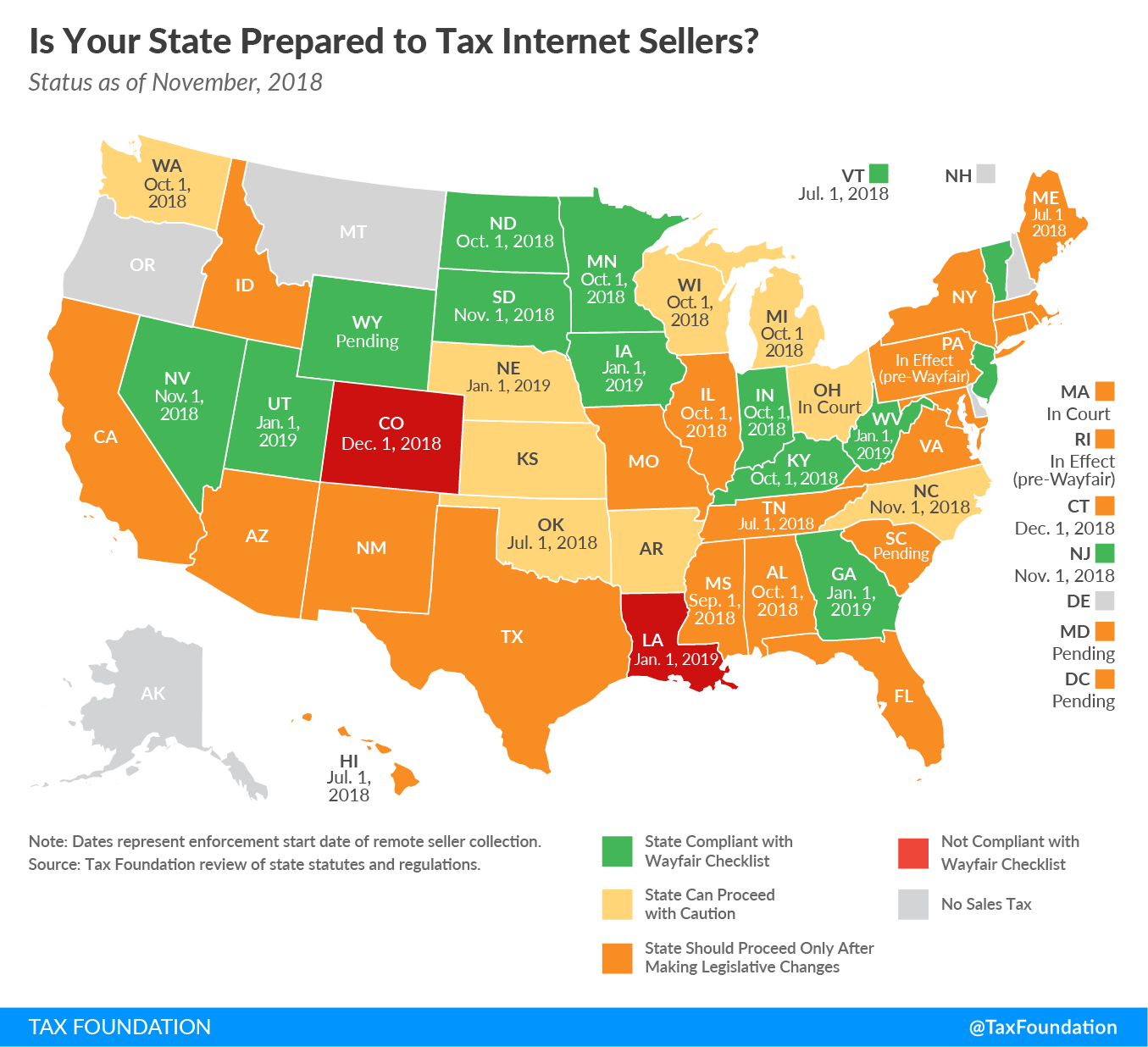

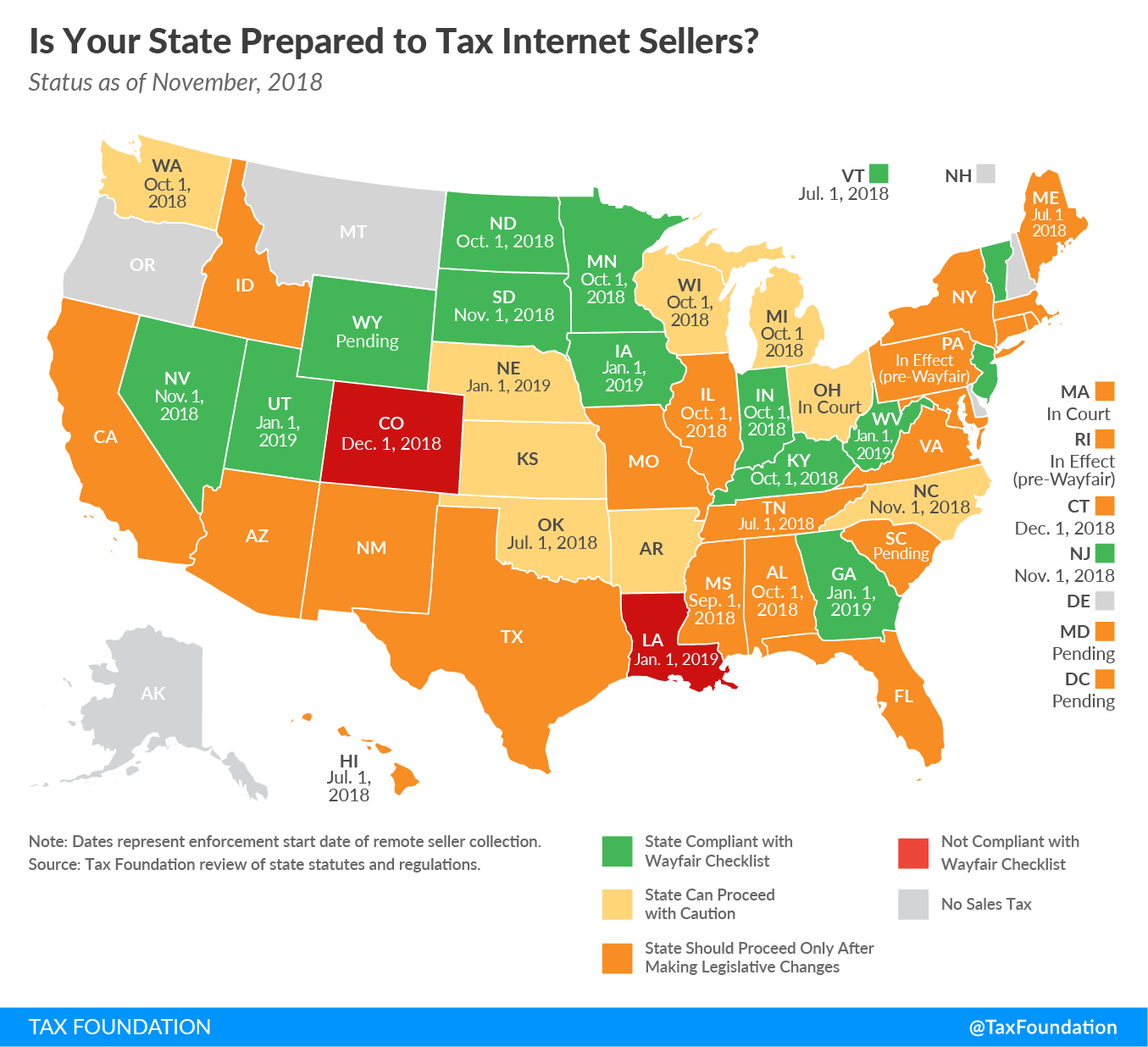

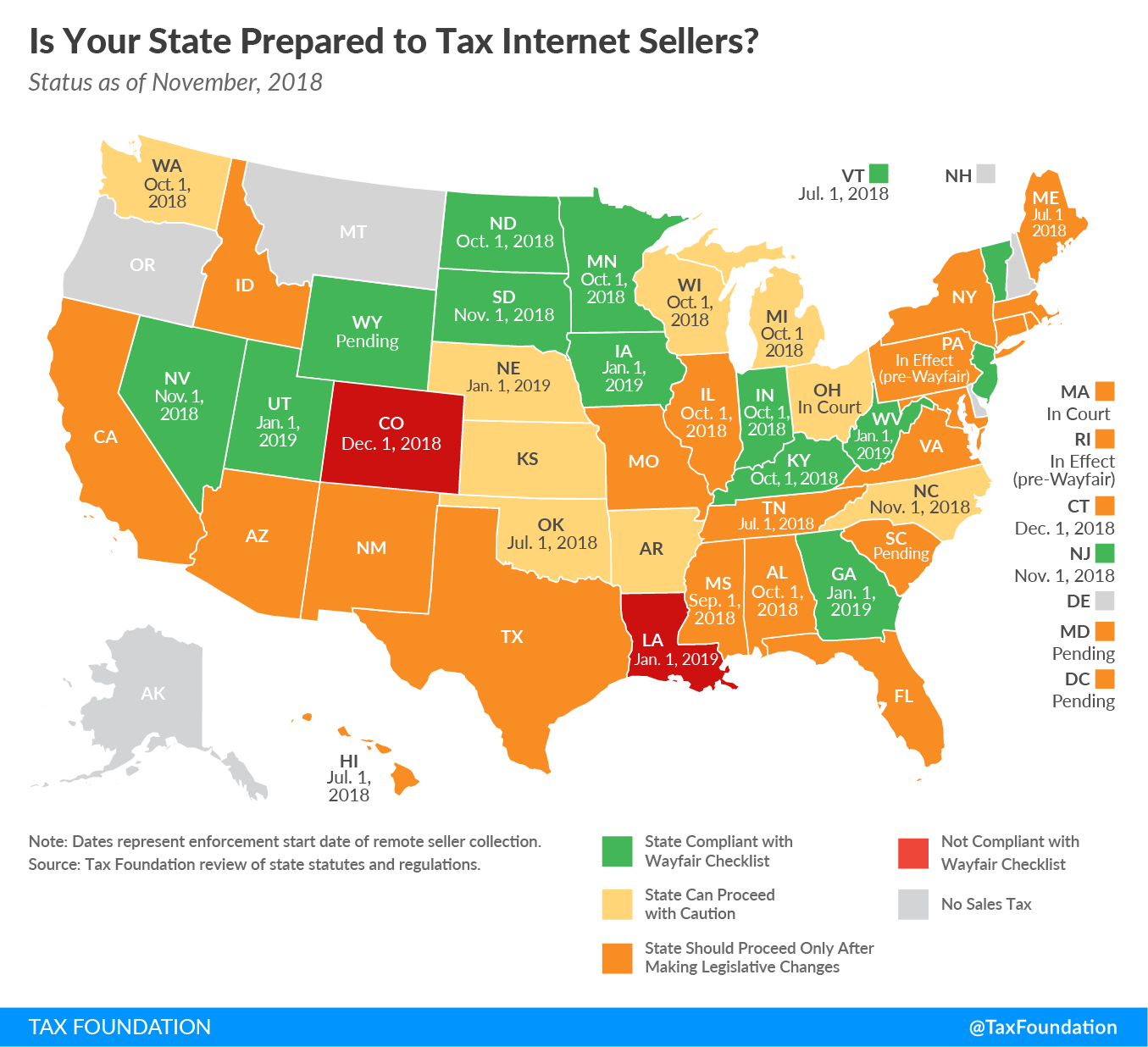

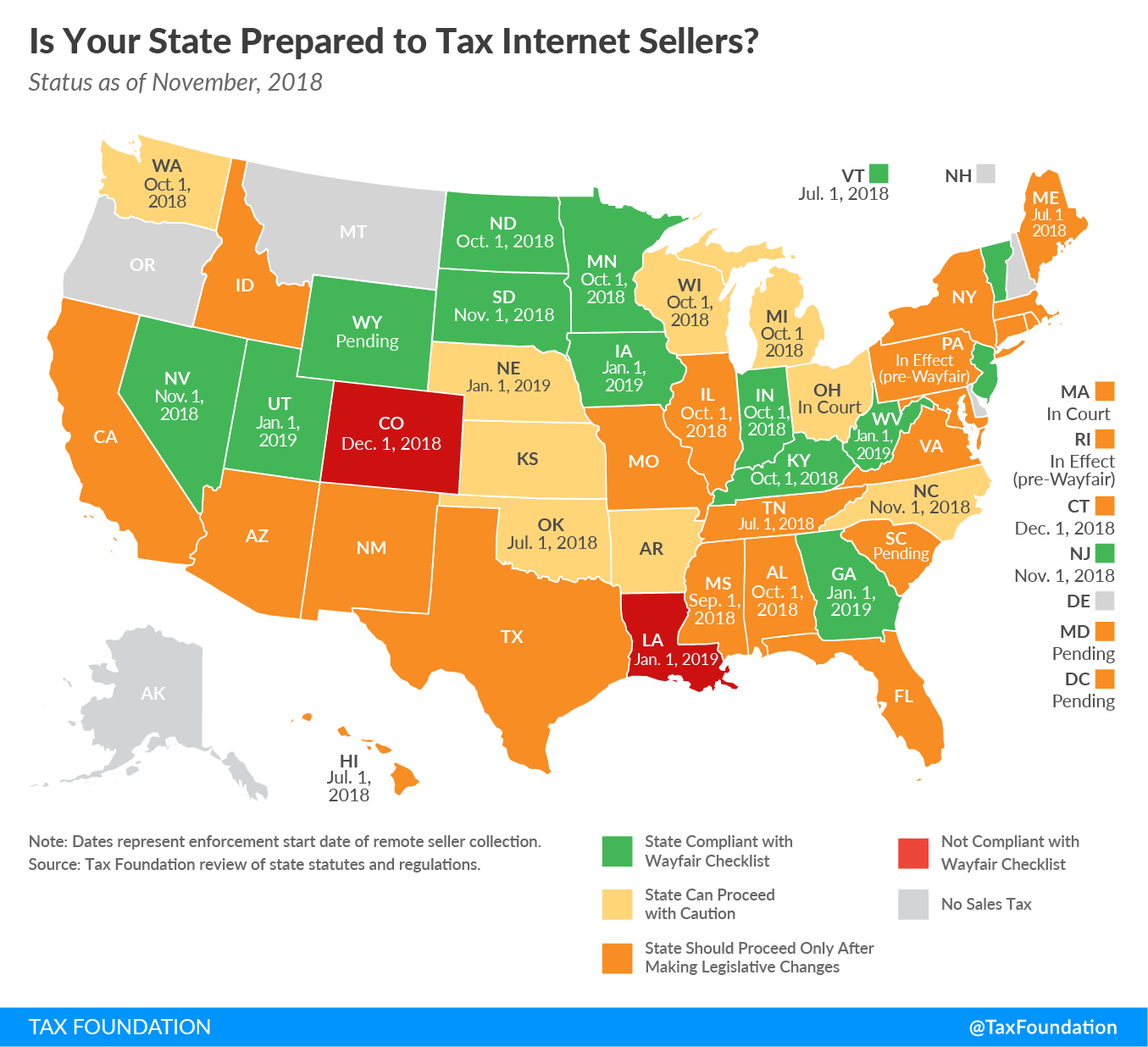

- The U.S. Supreme Court’s Wayfair v. South Dakota decision ushered in a new era of sales taxes on e-commerce and other remote sales, but many states have yet to implement the provisions the Court strongly suggested would protect such tax regimes from future legal challenges.

- A second state (Arizona) adopted a constitutional amendment banning the expansion of the sales tax to additional services, with similar efforts–which have the effect of locking an outdated sales tax base in place–expected to emerge in other states in 2019 and beyond.

- A court ruling has states scrambling to legalize and tax sports betting, while shifting public attitudes continue to render the legalization and taxation of marijuana an attractive revenue option in a growing number of states. In 2018, seven states adopted sports betting taxes, while two legalized and taxed marijuana.

- States continue to grapple with the appropriate taxation, if any, of e-cigarettes, with two states adopting taxes at rates reflective of vapor products’ potential for harm reduction, while the District of Columbia increased its tax to a punitive 96 percent rate.

- Business head taxes came out of nowhere to become a key consideration for several cities, particularly those with thriving tech sectors.

- Consideration of gross receipts taxes continue as corporate income tax revenues decline, though concerns about their economic effects have generally helped stave off their adoption.

- Two states repealed their estate taxes in 2018, continuing a decade-long trend away from taxes on estates and inheritances.

- Revenue triggers, a relatively modern innovation, again featured prominently in tax reform packages and will continue to do so.

Introduction

State tax policy decisions are not made in isolation. Changes in federal law, global markets, and other exogenous factors create a similar set of opportunities and challenges across states. The challenges faced by one state often bedevil others as well, and the proposals percolating in one state capitol often show up elsewhere. Ideas spread and policies can build their own momentum. Sometimes a trend emerges because one state consciously follows another, and in other cases, similar conditions result in multiple states trying to solve the same problem independently.

Identifying state tax trends serves a dual purpose: first, as a leading indicator providing a sense of what we can expect in the coming months and years, and second, as a set of case studies, placing ideas into greater circulation and allowing empirical consideration of what has and has not worked.

The adoption of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Wayfair v. South Dakota set off a chain reaction in state capitals, and the reaction to a Court decision on sports betting has been swift and enthusiastic in a growing number of states. As policymakers grapple with tax conformity under the TCJA, seek to craft Wayfair-compliant remote sales tax regimes, and figure out if and how to legalize and tax sports betting, they can and should learn from their peers.

Not all trends are driven by the federal government, of course. Shifting public attitudes toward marijuana have many states contemplating legalization as a new revenue stream, while declining collections from corporate income taxes have states grasping for alternatives. Ideas tried in one state–be it tax triggers, business head taxes, or changes to the sales tax base–often crop up elsewhere. The past year contains tax policy story lines that provide insights on the year to come.

Some trends worth noting have been with us for years, while others are just emerging; some are promising, while others might be thought of as cautionary; and some are time-constrained reactions to exogenous factors, while others represent innovations other states may wish to adopt. In all cases, policymakers can benefit from greater awareness of these developments.

Income Taxes

Across the country, income tax policies–both individual and corporate–were heavily influenced by the enactment of federal tax reform. States grappled with how to conform to the provisions of the new tax law, and in some cases sought to help their taxpayers circumvent its effects. The past year also saw further corporate income tax rate reductions and the adoption of reforms intended to enhance the neutrality of individual income tax codes.

IRC Conformity Updates

Most states begin their own income tax calculations with federal definitions of adjusted gross income (AGI) or taxable income, and they frequently incorporate many federal tax provisions into their own codes. The degree to which state tax provisions conform to the federal Internal Revenue Code (IRC) varies, as does the version of that code to which they conform. Some states have “rolling conformity,” meaning that they couple to the current version of the IRC, while others have “static conformity,” utilizing the IRC as it existed at some fixed date. Although exceptions exist, most states with static conformity update their conformity date every year as a matter of course.

The adoption of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) turned what had been routine into a serious policy deliberation. Most states stand to see increased revenue due to federal tax reform, with expansions of the tax base reflected in state tax systems, while corresponding rate reductions fail to flow down. The increase in the standard deduction, the repeal of the personal exemption, the creation of a deduction for qualified pass-through business income, the narrowing of the interest deduction, the cap on the state and local tax deduction (which affects state deductions for local property taxes), adjustments to the treatment of net operating losses, and enhanced cost recovery for machinery and equipment purchases, and even some of the provisions on the taxation of international income, flow through to the tax codes of some states—in different combinations, depending on the federal code sections to which they are coupled.[1]

States, therefore, were faced with choices. They could continue to conform to an older version of the IRC to avoid these revenue implications.[2] Alternatively, if conforming to the IRC post-TCJA, they could decouple from revenue-raising provisions, cut tax rates or implement other tax reforms to offset revenue increases, or do nothing, keeping the additional revenue.

The extent to which this is true (and indeed in some cases, whether it is true) depends on the federal tax provisions to which a state conforms. In 2018, five states–Georgia, Iowa, Missouri, Utah, and Vermont–adopted rate cuts or other reforms designed, at least in part, as a response to the expectation of increased revenue due to federal tax reform. Others, like Maryland and New York, rolled back some–but not all–of the federal changes to reduce the added state tax burden. States have generally been more willing to roll back changes to the individual income tax than to the corporate income tax. Finally, other states have been satisfied to retain the additional revenue, at least for now.

As of December 15, 2018, 32 states and the District of Columbia conformed to a version of the IRC which includes the reforms adopted under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (14 through updates to static conformity statutes). Another five states (Arizona, California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Virginia) conform to an older version of the code or expressly exclude changes implemented as part of the TCJA, while the remaining states either forgo an individual income tax or use state-specific calculations of income.[3] Many of these states have yet to grapple with the revenue implications of their decisions, and most have provided limited guidance on incorporated elements of the new system of international taxation, meaning that conformity issues will continue to dominate many legislatures in 2019.

SALT Deduction Cap Avoidance

By capping the state and local tax deduction (SALT) at $10,000, the new federal law set off a flurry of legislative activity in high-income, high-tax states. Policymakers had no shortage of inventive, if sometimes legally dubious, workarounds from which to choose. In broad terms, however, these efforts fell under three headings: (1) recharacterization of state and local tax payments as charitable contributions, thus evading the cap; (2) optional participation in an employer-remitted payroll tax regime to offset employees’ individual income tax liability, shifting payments to an uncapped arena; and (3) converting pass-through business owners’ income tax liability into an entity-level tax not subject to the cap. Each approach suffers from some combination of legal, practical, and distributional shortcomings.[4]

This trend is not without irony, as it involves some of the nation’s most progressive states–like New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut–taking great pains to reduce liability for their highest-income taxpayers even though most of these taxpayers already received a substantial tax cut under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut established an option of charitable contribution in lieu of taxes, which would be disallowed under draft guidance from the U.S. Department of the Treasury,[5] while a similar effort in California was vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown (D). Connecticut and Wisconsin enacted an entity-level tax on S corporations and partnerships, with a countervailing credit against the individual income tax liability of owners, to circumvent the cap, though in addition to any potential legal defects, the new tax can significantly complicate taxation for small businesses with income earned in, or partners located in, other states. And New York created an optional business payroll tax which would yield a credit against employees’ income tax liability, for much the same purpose—though with the further implication that taxpayers could receive the benefit of the standard deduction and a reduction in federal tax liability intended to replicate the state and local tax deduction, otherwise only available to filers who itemize.

It is possible that the pending Treasury guidance will put an end to the charitable contribution workarounds, but given the multiple permutations, it seems more likely that these efforts will continue at least another year or two.

Corporate Income Tax Rate Reductions

Corporate income taxes represent a small and shrinking share of state revenue, the product of a long-term trend away from C corporations as a business entity and ever-narrowing bases due to the accumulation of tax preferences. (The pass-through sector has grown dramatically, both in raw numbers and share of business income, over the past few decades, due in no small part to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which lowered the top individual income tax rate from 50 to 28 percent.[6])

In 2018, Connecticut permitted a 20 percent corporate income surtax on large businesses to decline to 10 percent, bringing the top marginal rate from 9.0 to 8.25 percent. The reduction was scheduled as part of an extension of the surtax adopted in 2015. In New Mexico, the top marginal corporate income tax rate declined from 6.2 to 5.9 percent, the culmination of a multiyear phasedown beginning with a top rate of 7.6 percent in 2017. Indiana’s corporate rate declined to 5.75 percent, continuing a series of reductions that will culminate in a 4.9 percent rate in 2022. In the District of Columbia, the final phase of a multiyear tax reform package saw the corporate franchise tax rate decline from 8.75 to 8.25 percent.[7]

Meanwhile, future rate reductions are scheduled in New Hampshire and North Carolina in 2019, and Missouri in 2020. New Jersey was the anomaly this year, hiking its corporate income tax.[8]

Although few states have repealed their corporate income taxes, their volatility, narrowing bases, economic impacts, and modest contribution to state revenues have all contributed to states’ decisions to reduce reliance on the tax.

Table 1. State Corporate Income Tax Rate Changes Since 2012

|

Source: Tax Foundation research.

|

| State |

2012 |

2018 |

Scheduled |

|

Arizona

|

6.968% |

4.9% |

— |

|

Idaho

|

7.6% |

7.4% |

— |

|

Illinois

|

9.5% |

7.75% |

— |

|

Indiana

|

8.5% |

5.75% |

4.9% |

|

Missouri

|

6.25% |

6.25% |

4.0% |

|

New Hampshire

|

8.5% |

8.2% |

7.9% |

|

New Mexico

|

7.6% |

5.9% |

— |

|

New York

|

7.1% |

6.5% |

— |

|

North Carolina

|

6.9% |

3.0% |

2.5% |

|

North Dakota

|

5.2% |

4.31% |

— |

|

Rhode Island

|

9.0% |

7.0% |

— |

|

West Virginia

|

7.75% |

6.5% |

— |

|

District of Columbia

|

9.975% |

8.25% |

— |

Federal Deductibility Limitations

Under federal deductibility, taxpayers can deduct federal tax liability from income in calculating their state tax liability. This provision, which only exists in six states, is the mirror image of the federal government’s state and local tax (SALT) deduction and is based on estimated liability to avoid a circular interaction with the federal government’s state and local tax deduction. It has the perverse effect of penalizing whatever the federal government incentivizes, and vice versa, as anything which incurs greater tax liability at the federal level reduces tax burdens at the state level.

The resulting distributions are convoluted and difficult to defend: things like having children, investing in your small business, or earning capital gains income, because they receive preferential tax treatment at the federal level, face higher effective rates in states with federal deductibility. Meanwhile, federal deductibility creates the mirror image of the federal government’s progressive rate structure. A graduated-rate state income tax and federal deductibility operate at cross-purposes with each other, but the result is not a flat tax but rather one where effective rates on marginal income fluctuate irrationally.

Only six states still permit a deduction for federal taxes paid, and thanks to reforms adopted this year, one of those states (Iowa) is set to repeal it entirely, and another (Missouri), which already caps the value of the deduction, adopted further restrictions on its availability. In both cases, federal deductibility is being traded for rate reductions and other structural reforms. Until recently, the remaining states offering federal deductibility thought of it as a “third rail.” Iowa’s breakthrough may well have changed that, paving the way for reforms in Missouri and potentially elsewhere.

Sales Taxes

In 2018, the Supreme Court upended the sales tax landscape by paving the way for states to apply their tax to remote sellers not physically present in the state. This outcome created new revenue opportunities for states, while simultaneously inducing them to simplify and modernize their tax codes. Unfortunately, some states continue to push in the wrong direction, resisting efforts to bring their sales tax systems in line with modern consumption patterns.

Remote Sales Tax Collection Regimes

E-commerce represented 9.8 percent of all retail sales in the third quarter of 2018,[9] a slice of the retail pie that states are increasingly able to capture in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision in Wayfair v. South Dakota, which struck down the physical presence requirement for substantial nexus.[10] After years of chafing at Quill, states won a major victory in court—and are now lining up to begin collecting.

Some states have incorporated tax simplification provisions commended in the Wayfair decision–what we have termed the “Wayfair Checklist”[11]–while others are moving forward with collections even though their tax codes are vulnerable to legal challenges on the grounds that they unduly burden interstate commerce. The factors present in South Dakota’s law, which the Supreme Court strongly suggested would protect it against any further legal challenges, include:

- A safe harbor for those only transacting limited business in the state;

- An absence of retroactive collection;

- Single state-level administration of all sales taxes in the state;

- Uniform definitions of goods and services;

- A simplified tax rate structure;

- The availability of sales tax administration software; and

- Immunity from errors derived from relying on such software.[12]

As of December 15, 2018, 34 states have adopted laws or regulations to tax remote sales, with legislation or administrative action pending in several others. Twelve of these states are clearly compliant with the Wayfair Checklist, and many others are undertaking improvements to shore up their remote sales tax regimes. However, some states–Louisiana is a particularly egregious example–are proceeding despite tax codes which impose significant burdens on remote sellers and raise serious legal issues. Colorado, another state with serious compliance issues, recently postponed remote sales tax collections.

Figure 1. State Taxation of Internet Sellers

In 2019, we can expect additional states to expand into the taxation of remote sales and should anticipate litigation in states which take too many shortcuts in their efforts to capture that revenue. Ultimately, the framework for those collections might have to be established over time through the courts, though states can and should avoid this by modeling their regime on the South Dakota law upheld by the Supreme Court.

Sales Tax Base-Narrowing Measures

Public finance scholars overwhelmingly agree that a well-designed sales tax base should extend to both goods and services while excluding business inputs.[13] Voters, however, are often skeptical of broadening the sales tax base, and we may be witnessing the beginning of a trend of tying policymakers’ hands on expansion to new services.

The exclusion of many services from most states’ sales tax bases is a historical accident, the result of sales taxes being implemented in an era when consumption was dominated by the sale of tangible goods and where the rudimentary tax systems in place would have made the taxation of services difficult. Today, however, services comprise more than two-thirds of all consumption, meaning that the sales tax omits most of what people purchase. Unchecked, this continual base erosion forces policymakers to raise rates or turn to other, often less efficient, taxes to raise the necessary revenue. Exempting services from the sales tax is also regressive, since services are consumed in greater proportion by wealthier households.

Ideally, policymakers should be exploring the expansion of the sales tax base, which can often help pay for other, much-needed tax reforms. Last year, however, Missouri voters ratified a constitutional amendment prohibiting base broadening to any service not already taxed, and this year, voters in Arizona followed suit.[14] On the heels of these victories at the ballot box, opponents of service taxation are already gearing up for similar ballot measures in other states.

These constitutional prohibitions prevent states from modernizing their sales tax, which in turn forces policymakers to turn to far less economically efficient sources of revenue.

Excise Taxes

Shifting public attitudes, a changing legal environment, and product innovations made are responsible for a spate of new or revised “sin” taxes on marijuana, sports betting, and vapor products, a trend likely to continue in coming years.

Taxation of Sports Betting

A U.S. Senator from New Jersey, basketball great Bill Bradley, was responsible for the 1992 legislation banning sports betting in the 46 states that had not already legalized it.[15] Earlier this year, a court case brought by New Jersey got that law struck down as unconstitutional. The Supreme Court’s decision in Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association opened the door to the legalization and taxation of sports betting, and states have wasted no time in entering the space.

Sports betting has changed since the 1992 law was enacted, particularly with the rise of daily fantasy sports. Not only can bettors lay odds on a team winning straight up or against the spread, but they can engage in fast-paced in-game betting. Will the next touchdown be scored by a wide receiver? Will the next shot be a three-pointer?

These in-game bets enhance the importance of the integrity of in-game data, at least theoretically. That has been the crux of argument advanced by professional sports leagues–particularly Major League Baseball (MLB) and the National Basketball Association (NBA)– for so-called “integrity fees,” in which as much as 1 percent of the “handle” (the total amount of bets taken) would be remitted to the league to offset the costs of maintaining the data on which bets are based, and in compensation for generating the product (the games themselves) which makes betting possible.

Many policymakers have questioned the justifications for these integrity fees. (Are existing league statistics somehow unreliable?) Some proponents are increasingly calling them royalties, which comes closer to explaining the real basis of the claim. Actual royalties, though, would not require the state to act as collector; unfortunately for sports leagues, there is little legal precedent to support the notion that statistics and scores constitute intellectual property. Thus far, states have spurned league efforts to insert them into sports betting legalization bills, though that may change with pending legislation in Michigan and Missouri.

States which have already legalized casino gambling are particularly likely to permit sports betting, but they should be conservative in their revenue estimates. Daily fantasy sports and other online options largely out of reach of state tax regimes will limit taxable betting activity, and collections are likely to be modest. If states adopt particularly high taxes–like the 51 percent of gross gaming revenues (revenues less winnings) sought by Rhode Island, or the 34 percent chosen in Pennsylvania[16]—they are likely to discourage in-person betting in competition with online alternatives which are far harder to tax. Or even competition down the road: Pennsylvania’s neighbor to the east, New Jersey, plans to tax sports betting at casinos and race tracks at 8 percent.[17]

Similar to issues raised by marijuana legalization, brick-and-mortar sports betting facilities will be competing with black and gray markets, and setting tax rates too high could keep bettors in untaxed markets. Initially, moreover, a state which legalizes sports betting may attract bettors across state lines, but this effect should dissipate as more states legalize wagering on sports. As of December 15, 2018, seven states (Delaware, Mississippi, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and West Virginia) had legalized sports betting in addition to Nevada, which already had a substantial sports betting regime.[18] Measures are pending in about two dozen more states.

Legalization and Taxation of Marijuana

As public attitudes toward marijuana have changed, states are increasingly revisiting their statutes on the possession, sale, and taxation of marijuana. Many states now allow medical marijuana, others have decriminalized possession, and a small but growing number have legalized recreational marijuana. Thus far, every state which has legalized marijuana has done so in concert with the implementation of a new excise tax regime.

A marijuana-specific tax regime is not theoretically essential, as it could, post-legalization, simply fall under the state sales tax like most other consumer goods. The notion that marijuana (like tobacco products, alcohol, and select other goods) should have its own tax regime has, however, been largely uncontroversial. These taxes also fund the states’ marijuana regulatory regimes, though in all cases they raise revenue considerably in excess of these costs and help fund general governmental expenditures.

Heading into 2018, seven states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) had legalized recreational marijuana, while implementation of a voter-approved measure in Maine had been delayed.[19] Of these, Alaska imposed a volume-based excise tax at $50 per ounce, while the remaining states imposed ad valorem taxes, such as Oregon’s 17 percent tax on marijuana. California has a hybrid system which includes both a 15 percent ad valorem tax and flat per-ounce taxes on flowers and leaves.

This year, Michigan voters legalized recreational marijuana and imposed a 10 percent excise tax. Missouri voters, meanwhile, were given a menu of options: they could impose either a 4 or 15 percent tax via constitutional amendment, or a 2 percent tax with an initiated measure, each with revenue dedicated to a different set of priorities. Voters overwhelmingly selected the modest 4 percent rate.

North Dakota voters rejected marijuana legalization in November, but it is reasonable to expect that legalization will reach additional states each year, either at the ballot box or through legislation. Although legislation is pending or expected to be introduced in a number of states during the 2019 session, lawmakers across the country have demonstrated a marked preference for leaving the decision to voters at the ballot.[20]

Initially, excise taxes tended to be quite high. In 2016, the four states with recreational marijuana were Washington with a 37 percent excise tax, Colorado at 29 percent, and Alaska and Oregon at 25 percent. These rates may have been too high to drive out gray and black markets.[21] Since then, Alaska, Colorado, and Oregon have reduced marijuana tax burdens, and states which implemented marijuana excise taxes since then have tended to adopt lower rates. As more states contemplate marijuana legalization, they are likely to consider excise tax rates closer to those adopted in 2017 and 2018 than those set in 2016.

Taxation of Vapor Products

Nine states and the District of Columbia tax vapor products. E-cigarettes are themselves relatively new, and states have struggled to determine if and how to tax them. When smokers shift to vapor products, this reduces cigarette tax revenue, but given that a stated purpose of most tobacco taxes is to improve health outcomes and reduce health-related expenditures, the harm reduction associated with these alternative products must be taken into account. Taxing vapor products identically with, or even more heavily than, traditional tobacco products creates a disincentive for smokers to shift to a less harmful product.

This year, Delaware and New Jersey adopted volume-based excise taxes, at 5 and 10 cents per fluid milliliter, respectively, while the District of Columbia hiked its ad valorem tax to an astonishing 96 percent of wholesale price, a tax rate likely to discourage smokers from making the transition. As vapor products increase in popularity, more states are likely to consider taxing them.

Business Taxes

State and local governments continue to experiment with new (and often economically harmful) businesses taxes, though a couple of outmoded business taxes are on the way out.

Revival of Business Head Taxes

The past year saw a resurgence of “head” or capitation taxes, which had long since fallen out of favor. Historically, head taxes were levied on individuals. What they lacked in equity, they made up for in administrative simplicity—a key consideration in medieval and early modern times. As other tax options emerged, head taxes fell out of favor (and, in some cases, into disrepute as they transformed into discriminatory poll taxes). A few states experimented with employment-based head taxes, imposed on the privilege of working, and assessed against either the employer or the employee—but these have been relatively rare. They exist, in different forms, in Colorado, Pennsylvania, Washington, and West Virginia, for instance, though frequently the levy was low (commonly $10 a year in Pennsylvania).

Then 2017 came along and suddenly head taxes were back in vogue, kicked off by a proposal for a $500 per-employee “business head tax” on large businesses in Seattle, Washington, home of Amazon and other major technology companies. Other cities with thriving tech sectors, like Cupertino (home of Apple) and Mountain View (home of Alphabet, the parent company of Google) in California, quickly expressed interest as well.[22]

Officials in these cities have argued that some technology companies impose a significant burden on local infrastructure but that their employees, who often live outside jurisdictional lines, have little exposure to local taxes. Business head taxes have been sold as a way to rectify this perceived wrong, often with the intention of raising money for expanded homelessness prevention services.

Unfortunately, business head taxes have the potential to be deeply counterproductive, which is why Seattle quickly reversed its decision to impose one. Taxes on job creation are rare—and for good reason.[23]

Even when the tax is limited to large employers, its impact can be vast. Not only do thresholds often capture low-margin businesses like supermarkets, but even small companies can take a big hit if major employers reduce their footprint. That’s particularly true of suppliers or other complementary companies, or smaller tech companies that locate in these high-cost areas to take advantage of the benefits of “tech agglomeration.”

Seattle dropped its head tax, but Mountain View, which proceeded more collaboratively, secured voter approval for a business head tax at the ballot in November. They are unlikely to be the last.

Reduced Taxation of Capital Stock and Tangible Personal Property

States have been slowly but steadily eliminating or reducing reliance on tangible personal property taxes (generally levied on business property like equipment and fixtures) for years.[24] Similarly, most states outside the Southeast have repealed their capital stock taxes, with Pennsylvania, Missouri, Rhode Island, and West Virginia the most recent to abandon them, while New York is in the midst of a multiyear phaseout and Mississippi began one this year.[25] There appears to be an emerging consensus that these taxes impede economic growth and are ill-suited to the modern economy.

Gross Receipts Tax Consideration

Just over a decade ago, gross receipts taxes appeared to be on the verge of extinction, with the antiquated form of taxation persisting (at the state level) only in Delaware and Washington. In recent years, however, several states have turned to this highly nonneutral tax, chiefly as an alternative to volatile corporate income taxes. Ohio, Texas, and Nevada all adopted gross receipts taxes in the past decade, while several states–including California, Louisiana, Missouri, Oregon, West Virginia, and Wyoming–contemplated them over the past two years.

No new states adopted a gross receipts tax in 2018, but they remained under active consideration in Missouri, Oregon, and Wyoming. The circumstances behind this resurgence have not abated, and additional proposals can be expected in coming years.

Other Tax Issues

The estate tax continues to be repealed in a number of states, while revenue triggers continue to feature prominently in tax reform packages.

Declining Estate Tax Burdens

Until 2005, taxpayers received a federal credit for state inheritance and estate taxes paid, essentially rendering them (up to a certain limit) a way for states to raise additional revenue at no additional cost to their taxpayers. Since the phaseout of that provision, states have been moving away from estate and inheritance taxes, a trend that continues unabated. Before the credit’s repeal, all 50 states had an estate or inheritance tax. Today, only 17 do, with two states–Delaware and New Jersey–repealing their estate taxes effective January 1, 2018. (New Jersey also imposes an inheritance tax. With estate tax repeal, Maryland is now the only state to impose both an inheritance and an estate tax.)[26]

As part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the federal exclusion amount was doubled to $11.2 million as of 2018, which in turn prompted higher exemption thresholds in a number of states which conform to federal provisions. There is a growing realization, moreover, that estate taxes can be counterproductive, driving high-net-worth retirees (who tend to be highly mobile) out of state, thus losing not only the potential estate tax revenue, but also years of income, sales, property, and other tax collections. There is every reason to expect that more states will follow in the footsteps of Delaware, New Jersey, and those that have already abandoned these taxes.

Continued Use of Revenue Triggers

After a lull in 2017, tax triggers reemerged in a big way in 2018, featuring in major tax reform packages in Iowa and Missouri. Triggers are an increasingly popular mechanism for phasing in tax reform measures subject to revenue availability. When designed correctly, triggers limit the volatility and unpredictability associated with changes to the tax code and can be an important part of the toolkit for states seeking to balance the economic impetus for tax reform with a governmental interest in revenue predictability.

In Iowa, the past year saw the adoption of a significant tax reform package which will ultimately lower individual and corporate income tax rates, repeal the alternative minimum tax, modestly broaden the sales tax base, and phase out an outmoded policy of federal deductibility. In Missouri, rate cuts were paired with the elimination of some exemptions and a narrowing of federal deductibility. Iowa is using triggers to phase in a number of its reforms, including the rate reductions, while Missouri adopts rate cuts in tandem with revenue-raising reforms, then resumes a previously-adopted schedule of tax triggers to implement further rate reductions subject to revenue availability.

Over the past decade, 12 states and the District of Columbia have turned to tax triggers to implement contingent tax rate reductions or other reforms. It is a trend that can be expected to continue, as well-constructed triggers can enhance stability and aid states in implementing tax policy changes in a fiscally responsible manner.[27]

Conclusion

The year 2018 was an eventful one in the realm of state taxation, but there is little to suggest that activity will slacken in the year to come. State interest in taxing remote sales and legalizing and taxing both sports betting and marijuana should continue unabated. While most states now conform, at least in part, to the new federal tax law, many important considerations–from how to handle the international provisions to what to do with the revenue–were postponed and will continue to dominate the tax conversation in 2019 and beyond.

Long-term trends, like the declining importance of corporate income taxes and starker economic implications of retaining an estate tax, will continue to figure into states’ tax considerations, while new mechanisms like tax triggers can be expected to feature prominently in future tax reforms. In recent years, moreover, tax plans have increasingly been comprehensive, reforming multiple taxes at once rather than being limited to a single tax. Often previously considered too daunting, comprehensive reform is increasingly viewed as more practical, as it allows reforms to be balanced against each other. In 2018, Iowa became the latest state to adopt a comprehensive reform package, but with several other states already gearing up for significant reform pushes, it will not be the last.

George Santayana’s maxim that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it is widely cited. Two sentences prior, he wrote, “Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness.”[28] Whatever progress policymakers wish to make on tax policy in 2019, they would do well to begin by internalizing the lessons to be gleaned from other states’ efforts in recent years.

Notes

[1] See generally Jared Walczak, “Tax Reform Moves to the States: State Revenue Implications and Reform Opportunities Following Federal Tax Reform,” Jan. 31, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-conformity-federal-tax-reform/.

[2] In some cases, the implications cannot be wholly avoided by failing to conform to the IRC post-TCJA. For instance, Virginia expressly decouples from the provisions of the new federal law, but it requires a filers’ choice to take the federal standard deduction to be replicated on their state tax forms. Because many more filers will benefit from taking the federal standard deduction, Virginia can expect additional revenue as these filers must now take Virginia’s standard deduction even though, all else being equal, they would benefit from being able to itemize at the state level.

[3] State statutes; Bloomberg Tax; Tax Foundation research.

[4] See generally Jared Walczak, “State Strategies to Preserve SALT Deductions for High-Income Taxpayers: Will They Work?” Tax Foundation, Jan. 5, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-strategies-preserve-state-and-local-tax-deduction/.

[5] U.S. Department of the Treasury, REG-112176-18, “Contributions in Exchange for State or Local Tax Credits,” 83 Fed. Reg. 43563 (Aug. 27, 2018).

[6] Scott Greenberg, “Pass-Through Businesses: Data and Policy,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 17, 2017, 7, https://taxfoundation.org/pass-through-businesses-data-and-policy/.

[7] Jared Walczak, “State Tax Changes That Took Effect on January 1, 2018,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 2, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-tax-changes-took-effect-january-1-2018/; Tax Foundation research.

[8] Ben Strachman and Scott Drenkard, “Business and Individual Taxpayers See No Reprieve in New Jersey Tax Package,” Tax Foundation, July 3, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/individual-income-tax-corporate-tax-hike-new-jersey/.

[9] U.S. Census Bureau, “Quarterly Retail E-Commerce Sales, 3rd Quarter 2018,” CB18-173, Nov. 19, 2018, https://www.census.gov/retail/mrts/www/data/pdf/ec_current.pdf.

[10] South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., 585 U.S. ___ (2018).

[11] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, Hannah Walker, and Denise Garb, “Post-Wayfair Options for States,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 29, 2018, 6, https://taxfoundation.org/post-wayfair-options-for-states/.

[12] Id.

[13] Business inputs are excluded to avoid what is known as tax pyramiding, where the final price includes the sales tax embedded at multiple points across the production process. In an optimal sales tax, only final consumption is subject to taxation.

[14] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, Jared Walczak, and Katherine Loughead, “Results of 2018 State and Local Tax Ballot Initiatives,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 6, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/2018-state-tax-ballot-results/.

[15] Brent Johnson, “The Story of When N.J. Almost Legalized Sports Betting in 1993,” NJAdvanceMedia.com, March 15, 2015, https://www.nj.com/politics/index.ssf/2015/03/the_story_of_njs_missed_opportunity_on_sports_bett.html.

[16] Ryan Prete, “States Cash in on Sports Betting Taxes, More Expected to Play,” Bloomberg Tax, Aug. 1, 2018, https://www.bna.com/states-cash-sports-n73014481301/.

[17] Howard Gleckman, “6 Reasons Why States Shouldn’t Be Counting Their Sports Betting Tax Revenue Yet,” Forbes, May 16, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2018/05/16/six-reasons-why-states-shouldnt-be-counting-their-sports-betting-tax-revenue-yet/.

[18] Ryan Rodenberg, “State-by-State Sports Betting Bill Tracker,” ESPN.com, Nov. 26, 2018, http://www.espn.com/chalk/story/_/id/19740480/gambling-sports-betting-bill-tracker-all-50-states.

[19] Samuel Stebbins, Grant Suneson, and John Harrington, “Pot Initiatives: Predicting the Next 15 States to Legalize Marijuana,” USA TODAY, Nov. 14, 2017, https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2017/11/14/pot-initiatives-predicting-next-15-states-legalize-marijuana/860502001/.

[20] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, Jared Walczak, and Katherine Loughead, “Results of 2018 State and Local Tax Ballot Initiatives.”

[21] Joseph Bishop-Henchman and Morgan Scarboro, “Marijuana Legalization and Taxes: Lessons for Other States from Colorado and Washington,” Tax Foundation, May 12, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/marijuana-taxes-lessons-colorado-washington/.

[22] Jared Walczak, “Business Head Taxes Take Aim at Having ‘Too Many Good Jobs,’” Tax Foundation, May 22, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/business-head-taxes-take-aim-many-good-jobs/.

[23] Jared Walczak, “Seattle Council Votes Overwhelmingly to Repeal New Business Head Tax,” Tax Foundation, June 12, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/seattle-city-council-votes-overwhelmingly-repeal-new-business-head-tax-2/.

[24] Joyce Errecart, Ed Gerrish, and Scott Drenkard, “States Moving Away from Taxes on Tangible Personal Property,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 4, 2012, https://taxfoundation.org/states-moving-away-taxes-tangible-personal-property/.

[25] Morgan Scarboro, “Does Your State Levy a Capital Stock Tax?” Tax Foundation, Oct. 5, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/state-levy-capital-stock-tax/.

[26] Jared Walczak, “State Inheritance and Estate Taxes: Rates, Economic Implications, and the Return of Interstate Competition,” Tax Foundation, July 17, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/state-inheritance-estate-taxes-economic-implications/.

[27] For a consideration of the elements of tax trigger design, see Jared Walczak, “Designing Tax Triggers: Lessons from the States,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 7, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/designing-tax-triggers-lessons-states/.

[28] George Santayana, The Life of Reason: The Phases of Human Progress (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1906), Vol, 1, Ch. XII.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Tax Trends Heading Into 2019

by r Hampton | Dec 18, 2018 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Tax Expenditures Before and After the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

Key Findings

- A tax expenditure is a departure from the normal tax code that lowers a taxpayer’s burden, such as an exemption, deduction, or credit.

- The list of tax expenditures in a tax system depends heavily on what one considers the normal tax code to be.

- Some tax expenditures are special preferences for particular kinds of economic activity. These may deserve elimination in order to fund broader tax relief, or they may be better off as spending programs for the purpose of more transparent government accounting.

- Some tax expenditures are attempts to change the U.S. tax system more broadly, often moving the tax code closer to systems employed by other OECD countries. These piecemeal efforts to change the U.S. tax code suggest that a broad reform to redefine the tax base would be welcome.

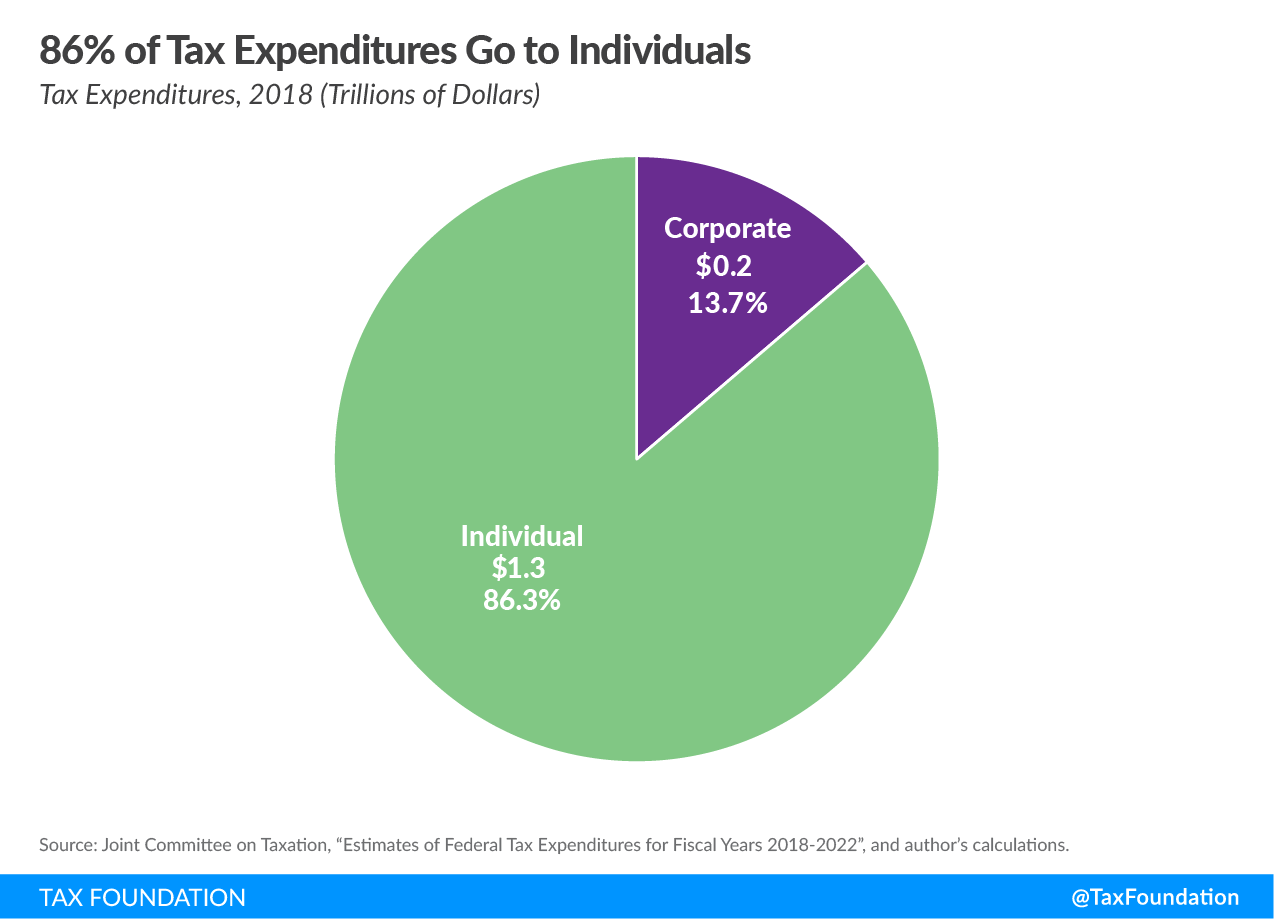

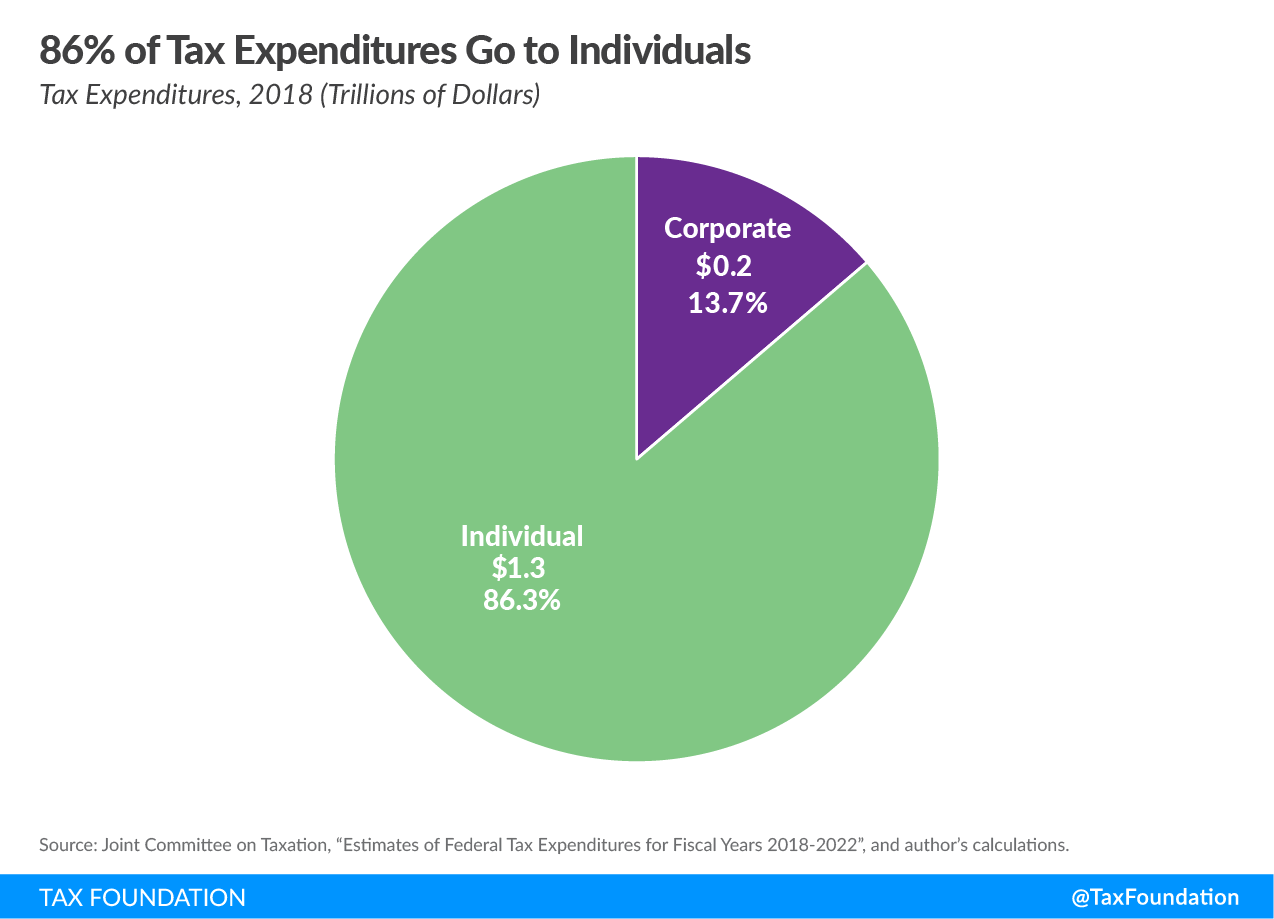

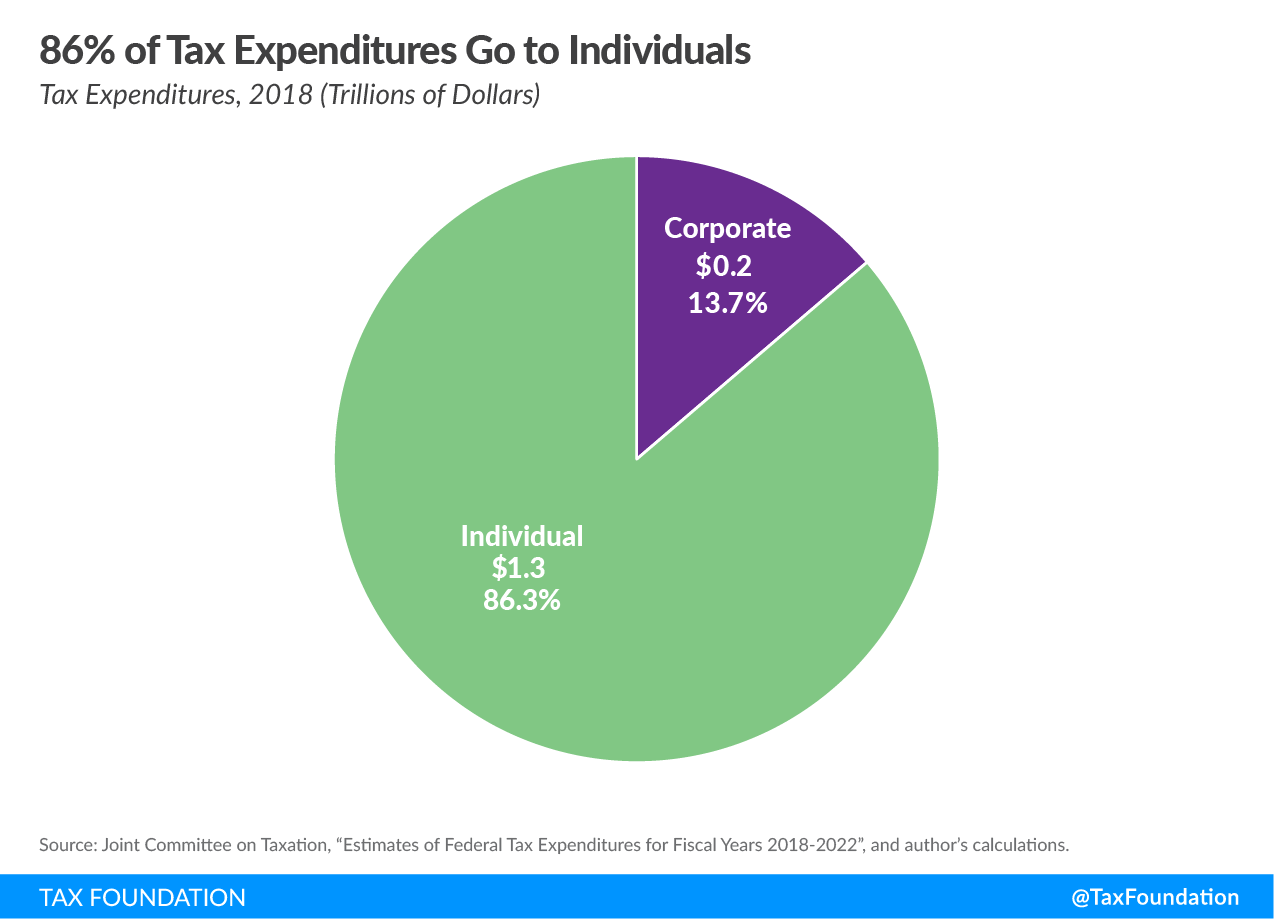

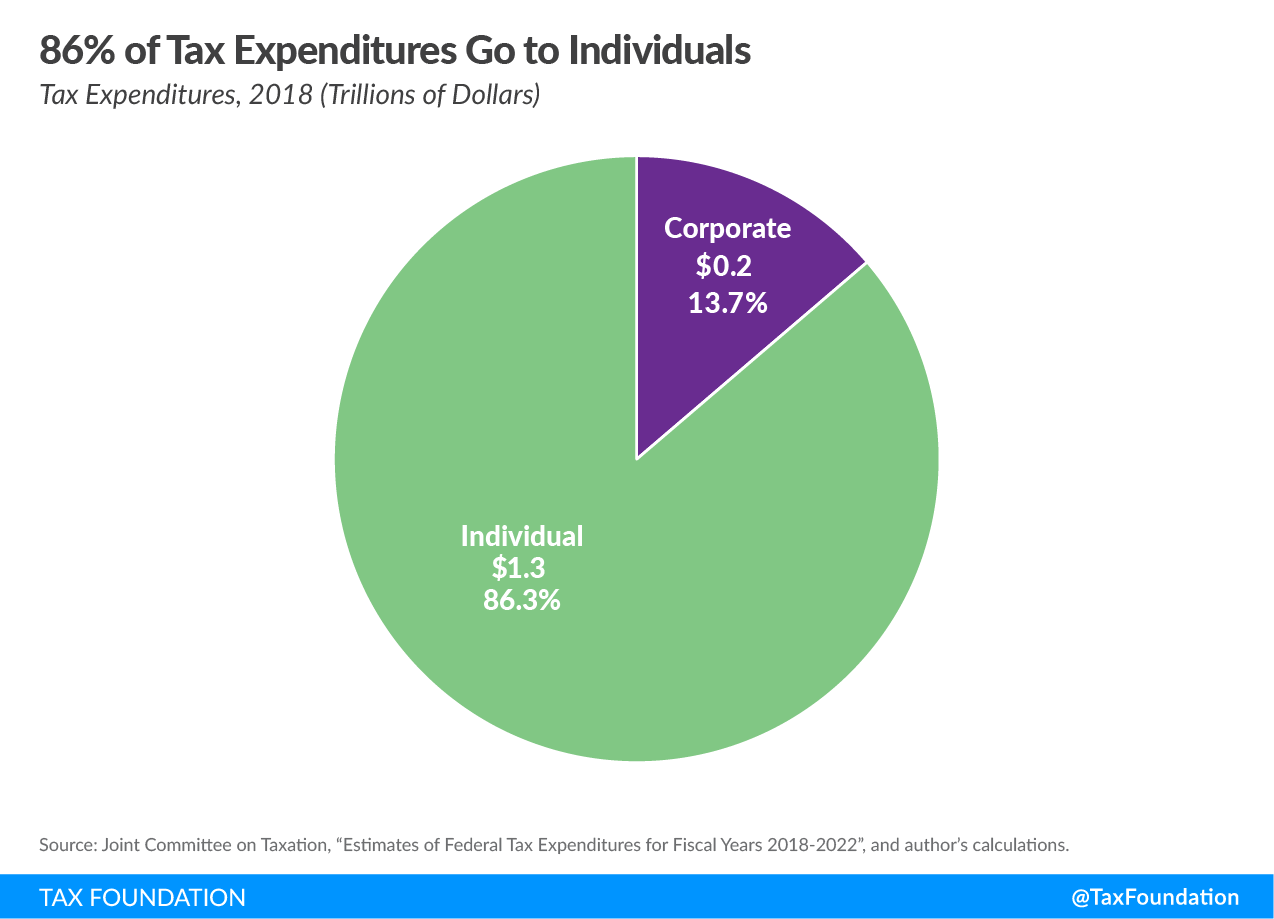

- The projected cost of tax expenditures in 2018 is $1.5 trillion, with $1.3 trillion in individual expenditures and $0.2 trillion ($200 billion) in corporate expenditures.

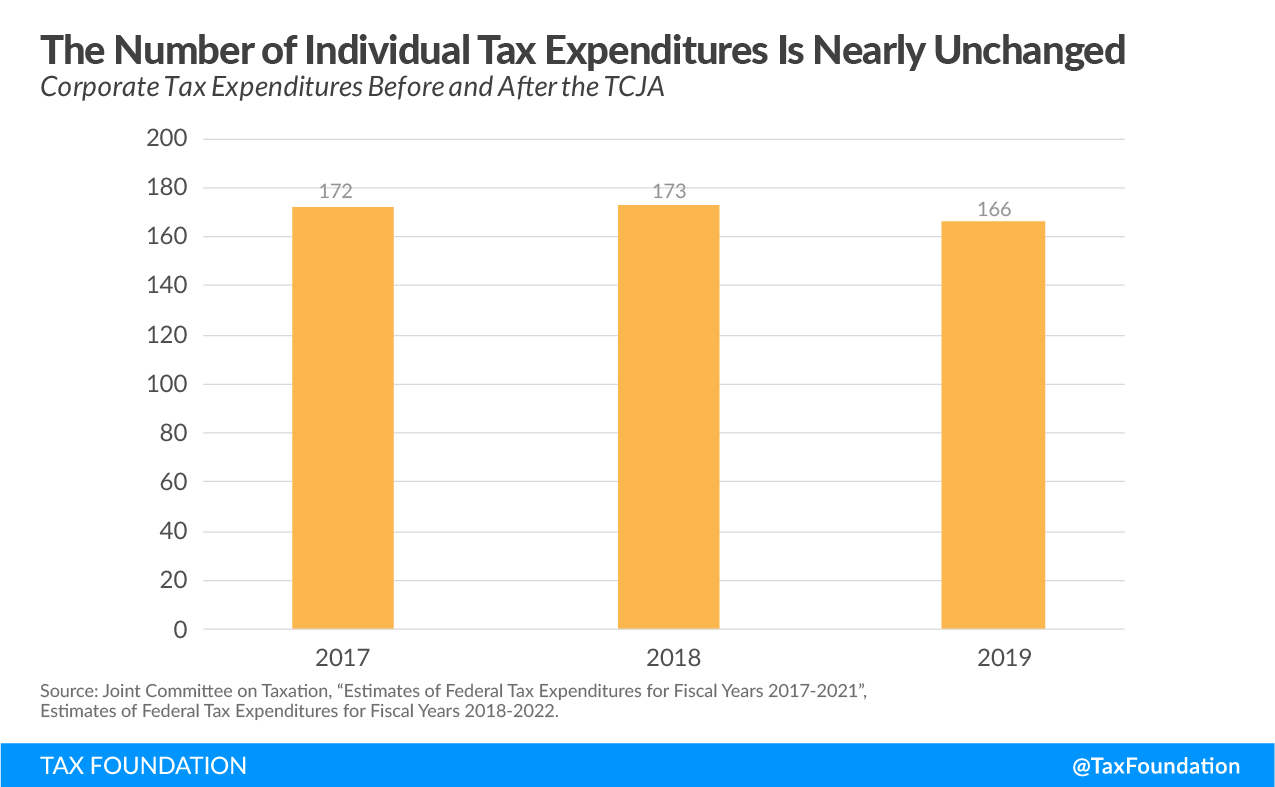

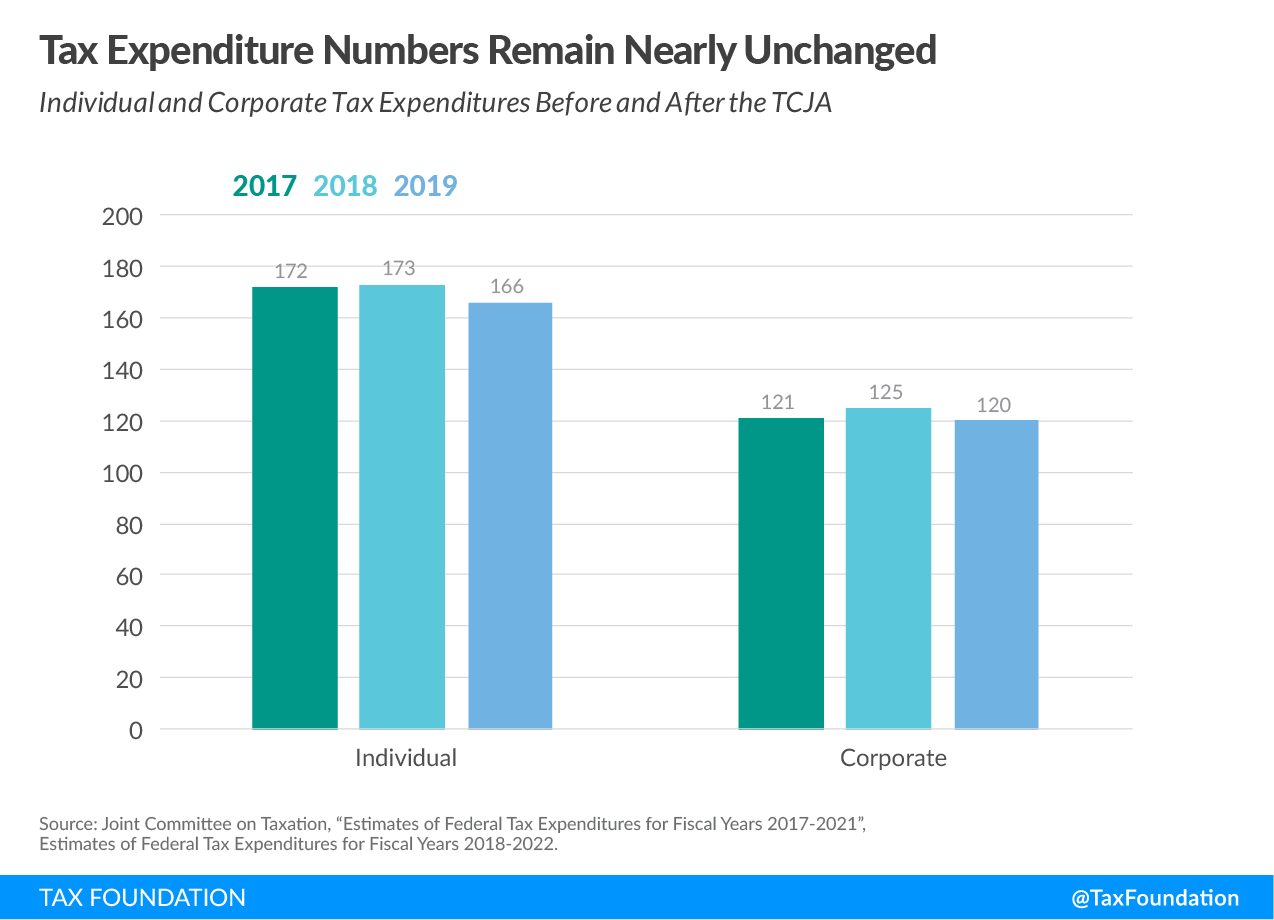

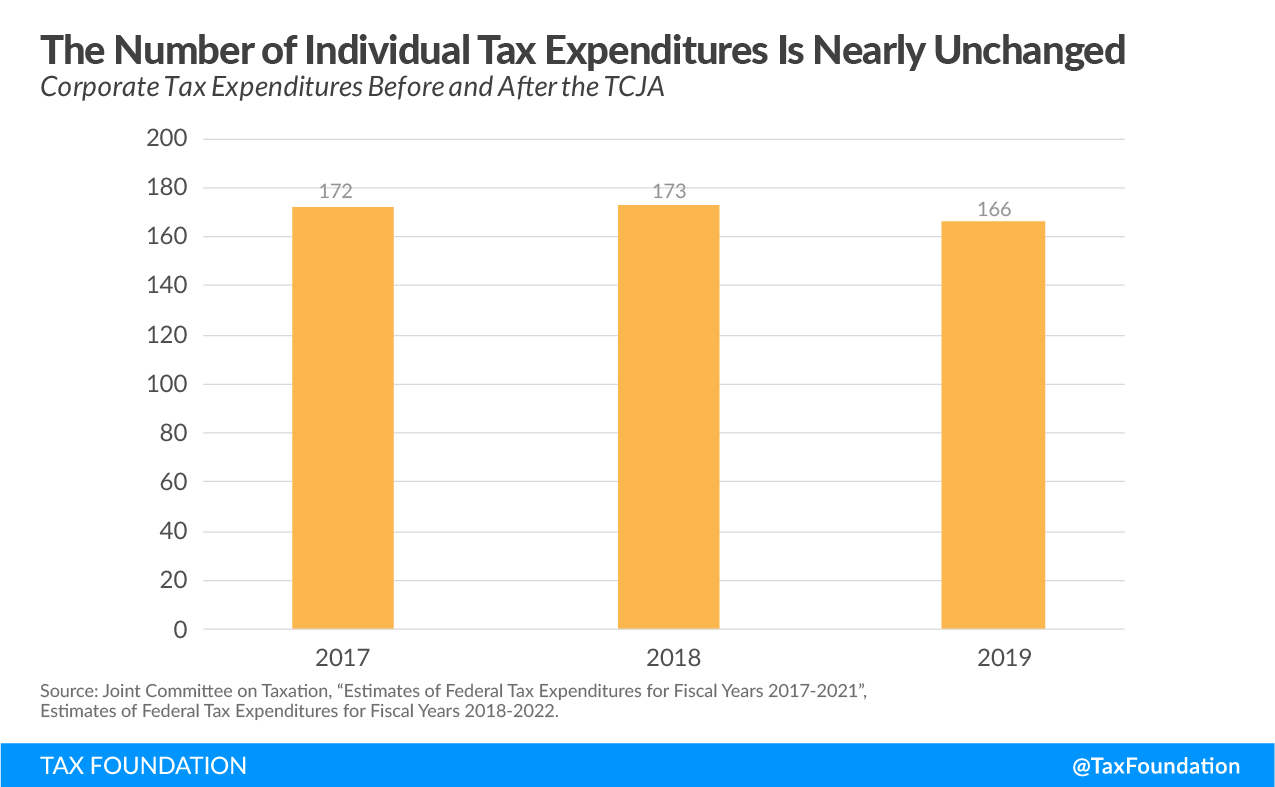

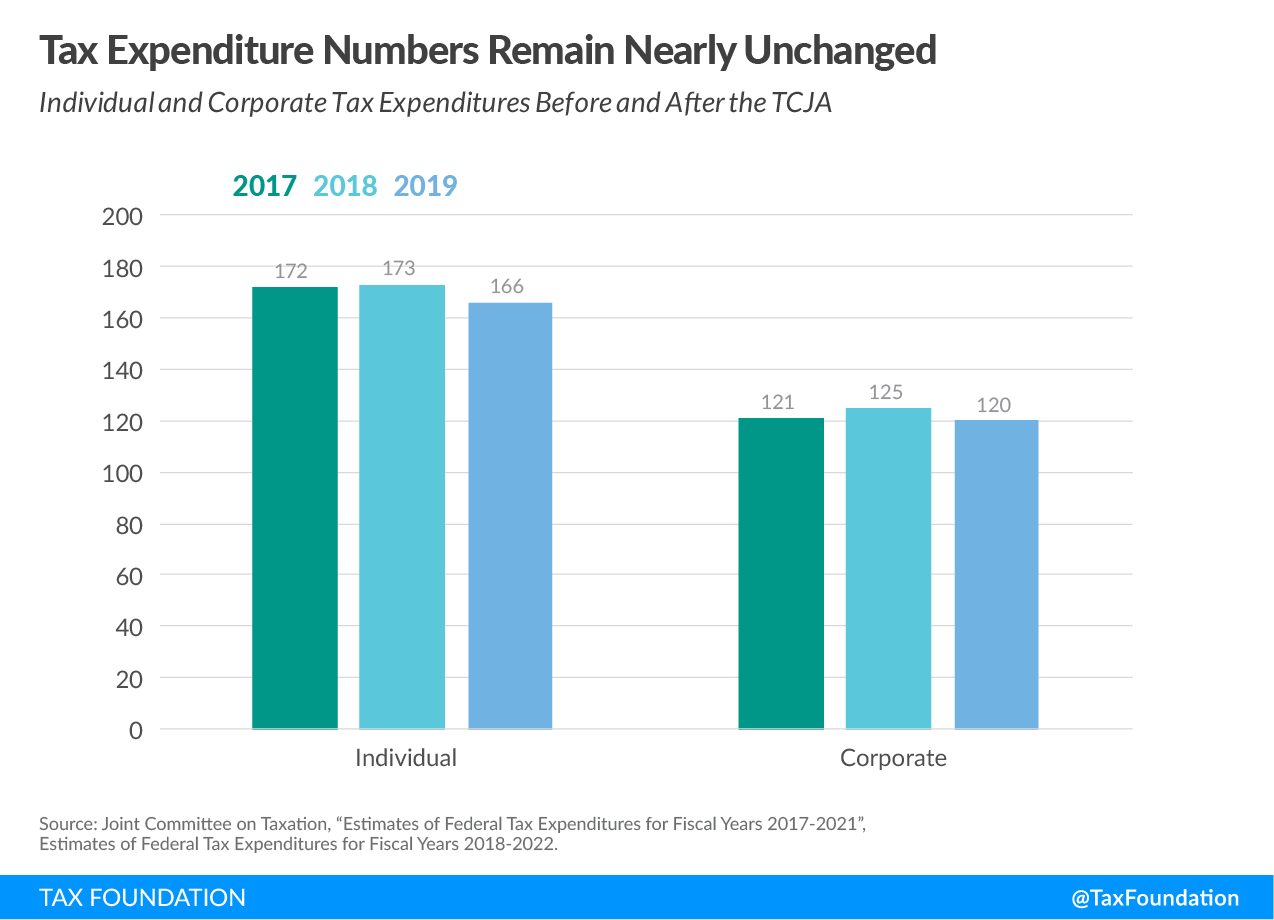

- The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did not reduce the number of tax expenditures. The number of individual tax expenditures increased from 172 in 2017 to 173 in 2018. Five individual tax expenditures were eliminated or set to expire, and six expenditures were added.

- The largest individual tax expenditures address health care, capital gains and dividends, and savings plans.

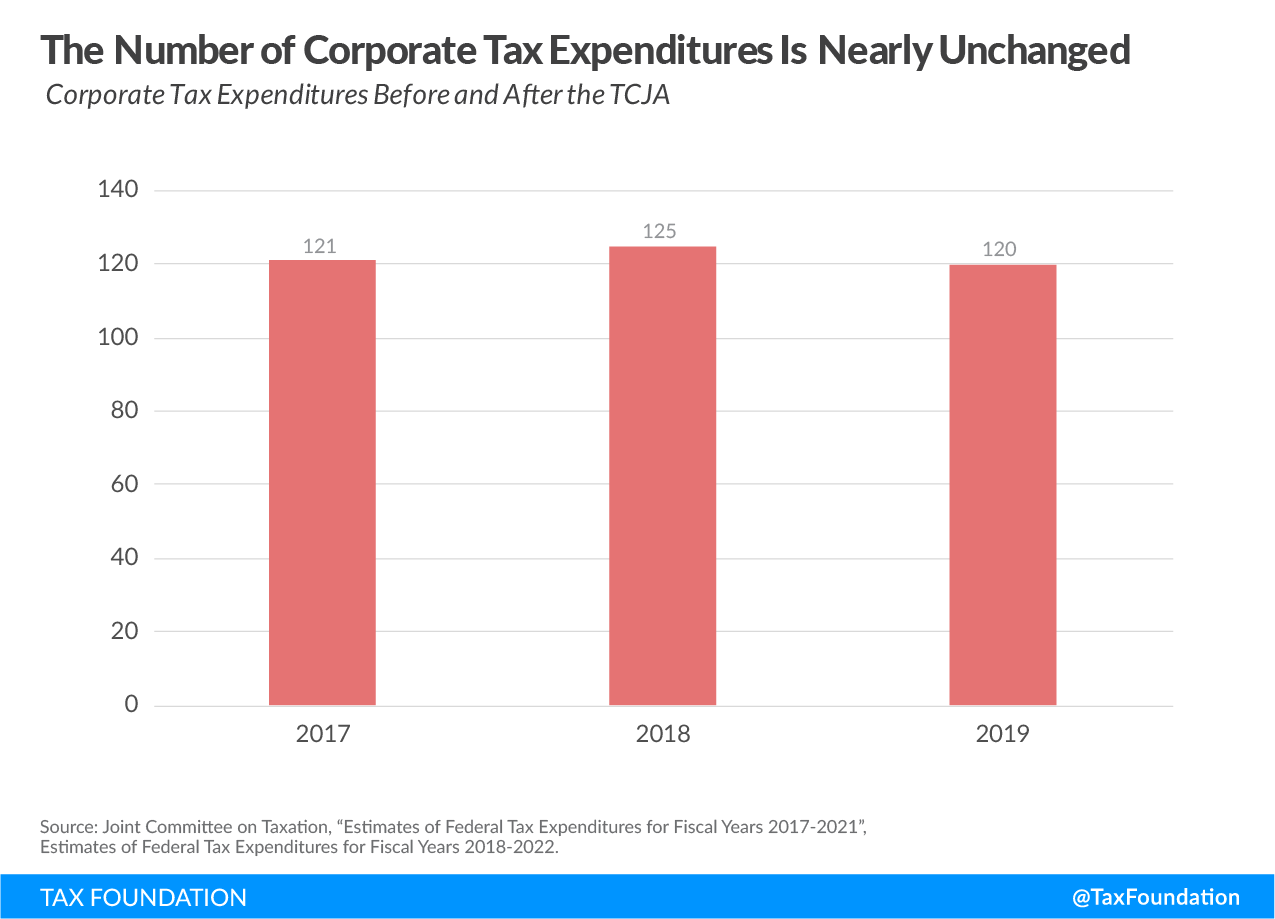

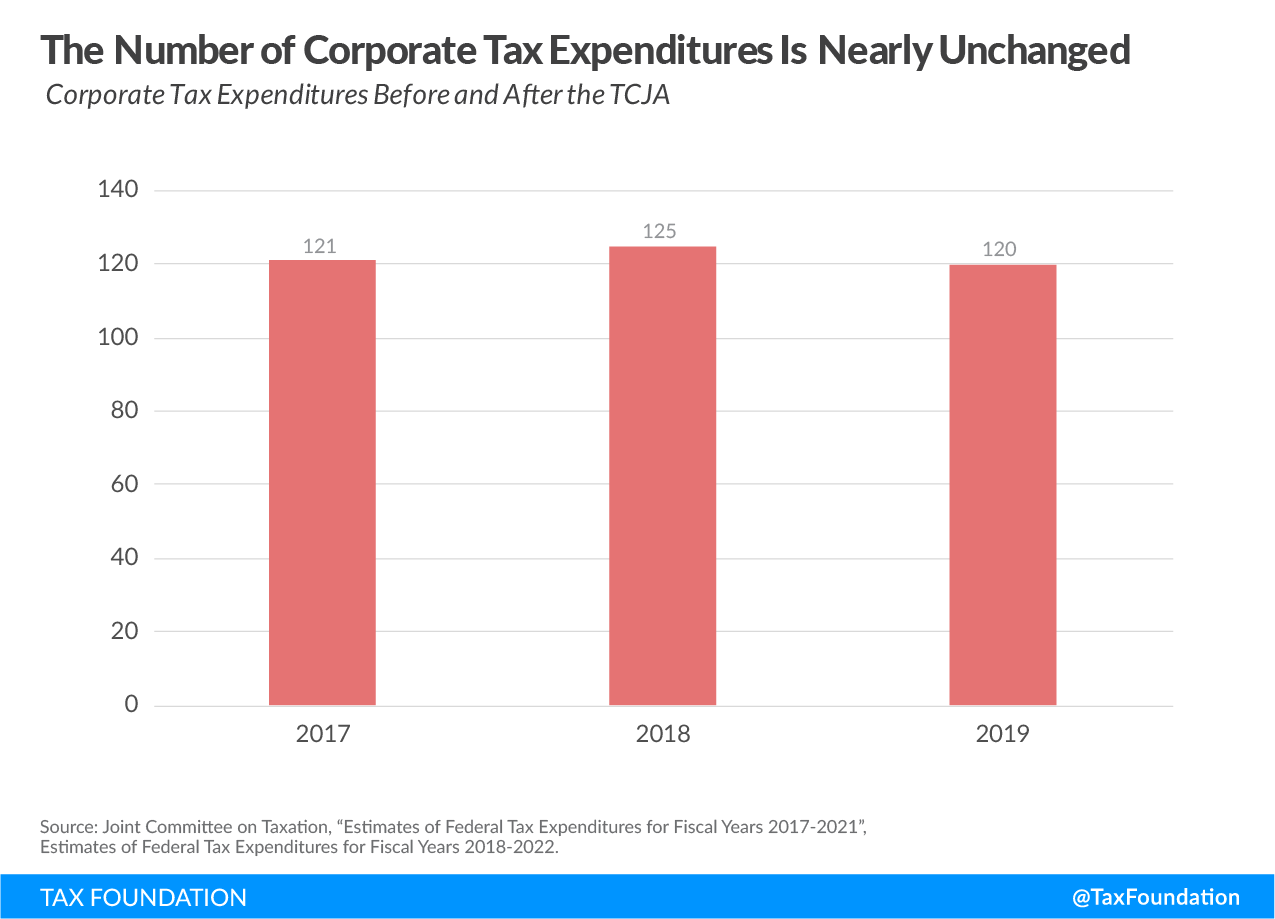

- The number of corporate tax expenditures increased as well, from 121 in 2017 to 125 in 2018. Five tax expenditures were eliminated or set to expire, and nine expenditures were added.

- The largest corporate tax expenditures address depreciation of equipment and treatment of income earned internationally.

Introduction

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) made many substantial reforms to the tax code, but it left tax expenditures largely unchanged. A tax expenditure is a departure from the “normal” tax code that lowers a taxpayer’s burden, such as an exemption, deduction, or credit. They are called tax “expenditures” because, in practice, they resemble government spending.[1]

Many tax expenditures give preferential treatment for particular economic activities. These expenditures deviate from sound tax policy by making the tax code less neutral and shrinking the tax base. Some expenditures, however, are broad-based changes that move the U.S. toward a different tax system. These expenditures deserve closer scrutiny from policymakers.

A priority for future tax reform should be reviewing each tax expenditure and determining whether it serves a reasonable purpose and accomplishes that purpose in a reasonable way. Does it move us toward a different tax system? Is it spending on an important priority of society at large? Or does it narrowly provide a preference to a specific industry or activity? Answering these questions and classifying the expenditures is critical in determining which are worth keeping.

This paper reviews what tax expenditures are, the positive and negative effects they can have on the tax code, and the TCJA’s changes to tax expenditures.

A Brief History of Tax Expenditures

The idea of the tax expenditure was developed in the 1960s by Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Stanley Surrey. It officially became part of the tax policy lexicon in 1974, when Congress mandated that tax expenditures be recorded as part of the annual budget. Under that act, tax expenditures were officially defined as “revenue losses attributable to provisions of the Federal tax laws which allow a special exclusion, exemption, or deduction from gross income or which provide a special credit, a preferential rate of tax, or a deferral of tax liability.”[2]

This is a useful definition for highlighting spending on specific industries or social priorities and estimating the cost of including those provisions in the tax code. However, any measure of tax expenditures that begins from a particular tax system will always treat any change to it–no matter how broad–as a tax expenditure. It is therefore important to separate broad-based changes to the tax code from narrow preferences.

What is the Normal Tax Code?

Given that a tax expenditure is defined as a departure from the “normal” tax code, the nature of tax expenditures depends crucially on what the “normal” tax code is. The Treasury Department and Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) have adopted similar definitions, but while these definitions have been consistent, they are not economically coherent.

The federal tax system is built on a poor intellectual foundation; it relies heavily on a definition of income developed by economists Robert Haig and Henry Simons almost a century ago.[3] The Haig-Simons definition is that income equals the sum of your consumption and your change in net worth; I = C + ΔNW. This is a useful accounting identity. It tells us that what we don’t spend on consumption becomes accumulated saving. However, it is not necessarily a good tax base.

There is an issue with including both a person’s consumption (C) and his or her change in net worth (ΔNW) in the tax base. The issue is that a change in one’s net worth usually becomes consumption at a later date.[4] (For example, an average individual accumulates net worth throughout her working life and spends it down in retirement.) As a result, the Haig-Simons definition single-counts some kinds of consumption, but double-counts other kinds for the purposes of taxation.

A distortion like this one–where some kinds of economic production get taxed more than other kinds–is generally a drawback. But this particular distortion is unusually powerful because it artificially reduces the after-tax return to saving and investment. Since people’s saving and investment decisions are sensitive to expected after-tax returns, the result is substantially less capital formation, which means smaller increases over time in productivity, incomes, and employment.

There are, of course, alternative tax bases. Among these are sales taxes, value-added taxes, excise taxes, corporate income taxes, payroll taxes, and property taxes. All of these tax bases are used in various places around the world, and all have benefits and drawbacks. There is no objective reason to define any particular tax base as “normal” for the purposes of counting tax expenditures.

The chosen “normal” tax code in Washington includes an individual income tax based on the Haig-Simons definition paired with a corporate income tax—although Simons regarded the corporate income tax as a double tax that he did not include in his definition of income. At times, government bureaus also measure tax expenditures from the payroll taxes that fund social insurance programs like Social Security.

Even after defining the “normal” tax base, there are still many issues in methodology. For example, measuring some changes in net worth (like capital gains) is a difficult problem. A taxpayer’s net worth may include assets with ever-changing values. For this reason, changes in asset value are usually only recorded as capital gains (or losses) upon the sale of the asset.

This is certainly a departure from a pure Haig-Simons income tax–and as a “deferral of tax liability,” it would be considered a tax expenditure under the Haig-Simons definition–but it is too difficult to calculate. As a result, it is usually not considered a tax expenditure, and the “normal” tax code measures changes in net worth only when they are realized.

This is one of the many compromises that the Treasury and JCT have to make in order to nail down a definition of tax expenditures. Some of these choices are extremely significant. For example, progressive income tax brackets are not counted as a “preferential rate of tax.” As a result, the official list of tax expenditures appears to favor wealthier taxpayers, because the progressivity of the tax system is already assumed in defining the base.[5]

Additionally, personal exemptions and the standard deduction are generally considered not to be tax expenditures, but rather part of a structure that defines a zero-rate bracket.[6] Personal exemptions are a particularly curious example, because they effectively lower the tax bill for adults with more dependents. Child tax credits, which serve the exact same purpose, are considered to be tax expenditures.

Additionally, the corporate income tax (at any rate Congress chooses) is considered “normal,” even though it is duplicative with income taxes on shareholders.[7] This corporate tax code gets deductions for employee compensation and a particular kind of deduction for capital costs, known as the alternative depreciation system (ADS).[8] There is no particular reason to believe that this deduction for capital costs is the only “normal” one, and the U.S. has in fact experimented with many different systems over the last century. ADS, however, was the method in use at the time that tax expenditures were invented as a concept.

Given all of these metaphysical questions about what constitutes a normal tax structure, the true nature of tax expenditures will always be somewhat subjective. The particular nature of what constitutes a tax expenditure in Washington is partially economics, partially one’s value judgments, and partially historical accident. However, rather than devising an alternative measure of tax expenditures, this report will concern itself with tax expenditures as measured in practice.

Relative Size of Corporate versus Individual Tax Expenditures

The majority of the expenses incurred by tax expenditures comes from the individual side. JCT estimates that individual expenditures will cost $1.3 trillion in 2018, or 86.3 percent of the total cost of all expenditures, while corporate expenditures will cost $0.2 trillion ($200 billion), or 13.7 percent, for a total of $1.5 trillion.[9]

Figure 1

Individual Tax Expenditures

The TCJA increased the number of tax expenditures from 172 in 2017 (the year before the TCJA passed) to 173 in 2018.[10] Five tax expenditures were eliminated or set to expire, while six tax expenditures were added, resulting in a net increase.

Table 1 lists the new individual tax expenditures and their projected 2018 cost.

Table 1. New Individual Tax Expenditures

| Expenditure |

2018 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|

Note: A negative cost means that a provision is a negative tax expenditure, which raises revenue. JCT defines negative tax expenditures as “tax provisions that provide treatment less favorable than normal income tax law and are not related directly to progressivity.” Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2017-2021,” “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022.”

|

|

Limitation on net interest deduction to 30 percent of adjusted taxable income

|

-$0.9 |

|

Insurance companies’ two-year NOL carryback

|

$0.2 |

|

20 percent deduction for qualified business income

|

$33.2 |

|

Qualified opportunity zones

|

$0.4 |

|

Credit for family and medical leave

|

$0.2 |

|

Treatment of employee moving expenses

|

-$1.0 |

Table 2 lists the five individual tax expenditures that were eliminated or expired.

Table 2. Eliminated Individual Tax Expenditures

| Expenditure |

2017 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|

Note: JCT does not provide specific estimates for provisions that are estimated to cost less than $50 million over five years. Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2017-2021.”

|

|

Therapeutic research credit

|

$0.1 |

|

Expensing of research and experimental expenditures

|

N/A |

|

Treatment of income from exploration and mining of natural resources as qualifying income under the publicly-traded partnership rules

|

$0.1 |

|

Exclusion of income attributable to the discharge of principal residence acquisition indebtedness

|

$2.4 |

|

Deduction for higher education expenses

|

$0.4 |

However, several of the above provisions, such as the discharge of principal residence indebtedness and the deduction for higher education expenses, are likely to be extended for the 2018 tax year. These provisions, along with approximately 25 others, are generally extended on an annual basis as part of a package colloquially known as “extenders.”[11]

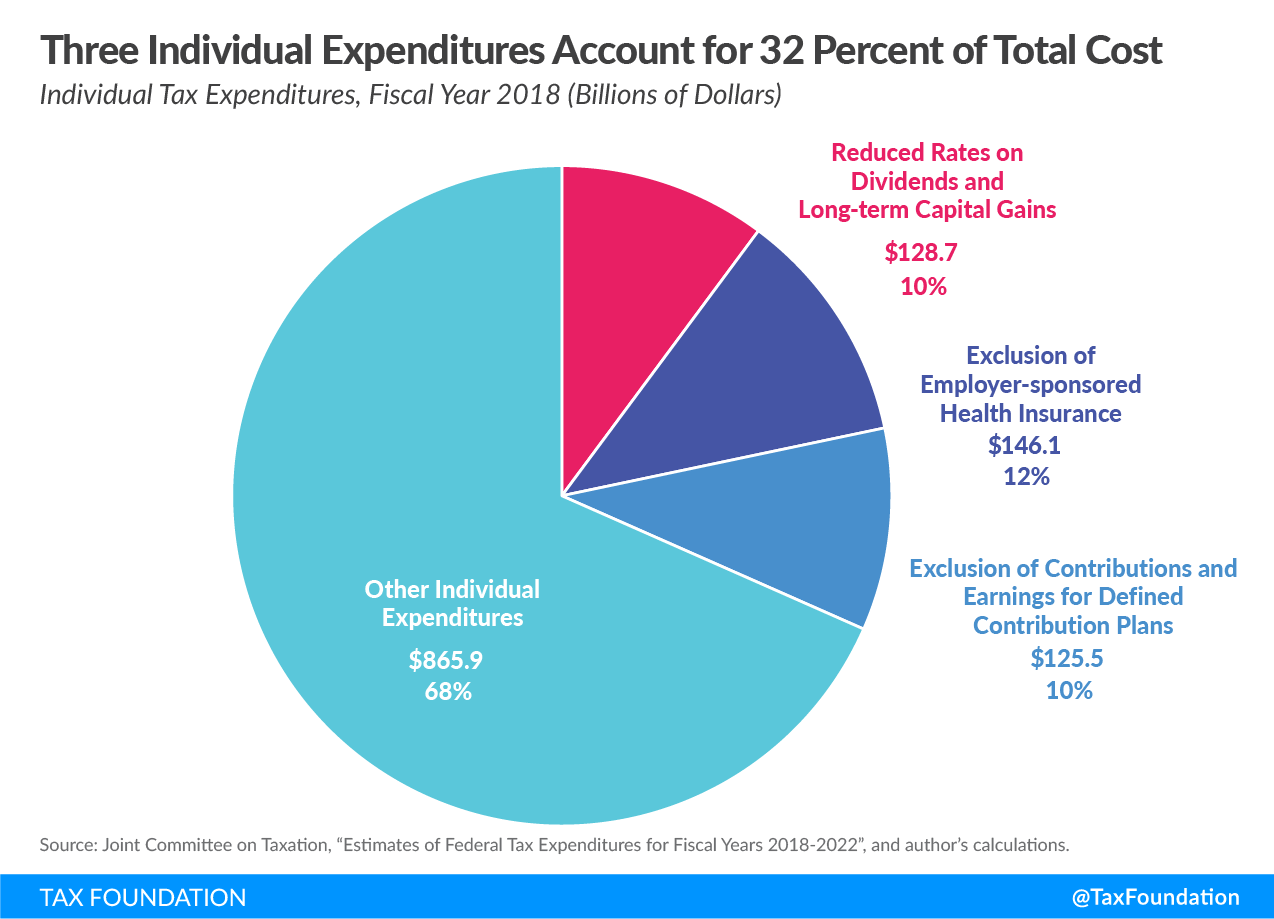

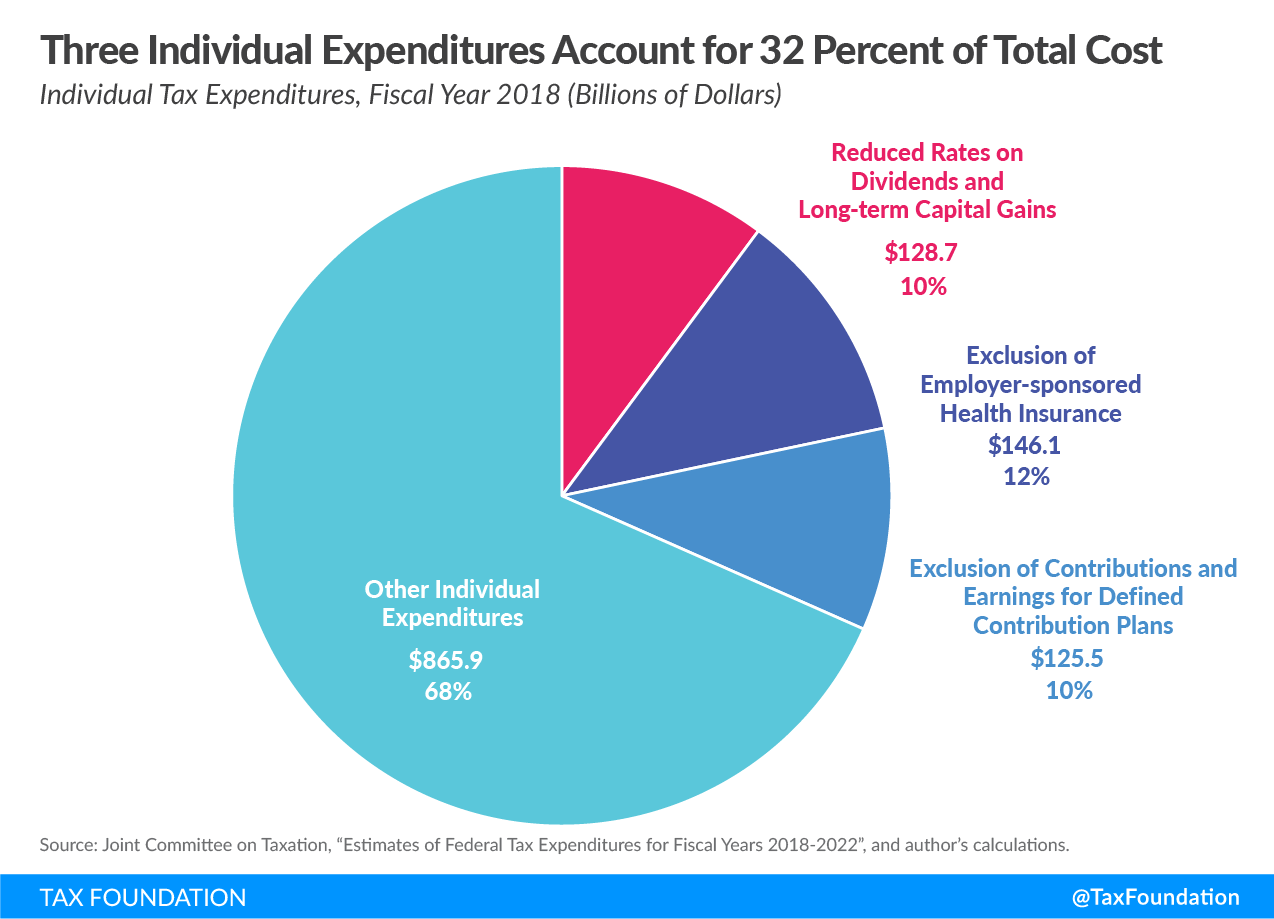

Figure 2 illustrates the largest individual tax expenditures for fiscal year 2018. Three tax expenditures make up roughly 32 percent of all individual tax expenditures. These expenditures are: the exclusion of employer contributions for health care, health insurance premiums, and long-term care insurance premiums; reduced rates of tax on dividends and long-term capital gains; and net exclusion of pension contributions. In total, individual tax expenditures are projected to cost $1.3 trillion in 2018.

Figure 2

Exclusion of Employer Contributions for Health Care, Health Insurance Premiums, and Long-term Care Insurance Premiums ($146.1 billion)

This expenditure excludes employer-paid health insurance premiums, long-term care insurance, and other medical expenses from employee gross income. Employer contributions to insurance premiums reflect a tax preference for those taxpayers with employer-provided health insurance, because they receive a form of labor compensation that goes untaxed. Taxable income would generally include all work compensation, including health benefits, under the baseline tax system.

This expenditure is also the clearest example of Congress prioritizing some economic activities over others. Health is no doubt important, but the use of the tax code to bundle employment together with health insurance is worthy of skepticism.[12]

Reduced Rates of Tax on Dividends and Long-term Capital Gains ($128.7 billion)

Under the baseline tax system, tax rates on income would range from 10 percent to 37 percent, plus a 3.8 percent surtax for high-income individuals. This expenditure sets a maximum rate of 20 percent, plus the 3.8 percent surtax, for qualified dividends and capital gains on assets held for more than one year and qualified dividends.[13] This is listed as a tax expenditure because the normal tax code defined by JCT includes a full Haig-Simons individual income tax in addition to a corporate income tax. This tax expenditure, in some ways, returns to a pure Haig-Simons definition, because it acknowledges and compensates for the corporate income tax on the individual side.

This is an example of a reform that is clearly designed as a move toward a different kind of tax system (perhaps, an equal tax on all income with corporate integration) but it does not represent special tax treatment for a specific sector of the economy. Rather, it is a deliberate attempt to move the tax code past the definition of normalcy that was chosen in the 1970s.

Net Exclusion of Pension Contributions and Earnings for Defined Contribution Plans ($125.5 billion)

This expenditure allows individual taxpayers and employers to make tax-preferred contributions to employer-provided 401(k)s and similar plans. In 2018, the employee exclusion limit for employees under age 50 is $18,500; for employees age 50 or over, the exclusion limit is $24,500. In 2018, the maximum exclusion for defined contribution plans, including both employee and employer contributions, is $55,000. The tax on both contributions and the investment income that plans earn is deferred until withdrawal.[14]

These are lowered tax burdens only in the sense that they are considered a “deferral” of tax liability from what is seen as the normal tax code. Many tax systems–like those for pensions in most countries, not just ours–defer tax liability on pension contributions until the money is paid. More broadly, this represents a move toward a style of tax known as the consumed income tax or inflow-outflow tax.[15]

Individual Tax Expenditures Set to Expire in 2019

Table 3 lists the seven individual tax expenditures that are scheduled to expire at the end of the 2018 tax year.

Table 3. Individual Tax Expenditures Scheduled to Expire at the End of 2018

| Expenditure |

2018 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|

Note: JCT does not provide specific estimates for provisions that are estimated to cost less than $50 million over five years. Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022.”

|

|

Credit for energy-efficient improvements to existing homes

|

$0.1 |

|

Deduction for premiums for qualified mortgage insurance

|

$0.8 |

|

Expensing of costs to remove architectural and transportation barriers to the handicapped and elderly

|

N/A |

|

Deduction for income attributable to domestic production activities

|

$1.2 |

|

Credit for Indian reservation employment

|

N/A |

|

District of Columbia tax incentives

|

N/A |

|

Parental personal exemption for students aged 19 to 23

|

$1.1 |

Importantly, current law assumes temporary provisions will expire as scheduled. But for more than a decade, lawmakers have continually reauthorized a set of provisions known as “tax extenders,” instead of allowing them to expire or making them permanent.[16] If lawmakers continue their ad hoc reauthorization of extenders, tax expenditures in 2019 will be larger in number and cost.

Nevertheless, according to current law, which does not account for likely extensions, there will be 166 individual tax expenditures in fiscal year 2019, compared to 172 in 2017.

Figure 3

Corporate Tax Expenditures

On the corporate level, the number of tax expenditures has increased as well, from 121 in 2017 to 125 in 2018. Five tax expenditures were eliminated or set to expire, while nine tax expenditures were added, resulting in a net increase.

Table 4 lists the new corporate expenditures and their projected 2018 cost.[17]

Table 4. New Corporate Tax Expenditures

| Expenditure |

2018 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2017-2021,” “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022.”

|

|

Base erosion and anti-abuse tax

|

-$2.9 |

|

Deduction for foreign-derived intangible income derived from trade or business within the United States

|

$9.6 |

|

Limitation on deduction for FDIC premiums

|

-$0.7 |

|

Limitation on net interest deduction to 30 percent of adjusted taxable income

|

-$8.8 |

|

Insurance companies’ two-year NOL carryback

|

$2.0 |

|

Treatment of employer-paid transportation benefits

|

-$1.5 |

|

Qualified opportunity zones

|

$1.1 |

|

Credit for family and medical leave

|

$0.5 |

|

Treatment of meals and lodging (other than military)

|

-$0.8 |

Table 5 lists the five corporate tax expenditures that were eliminated or expired.

Table 5. Eliminated Corporate Tax Expenditures

| Expenditure |

2017 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|

Note: JCT does not provide specific estimates for provisions that are estimated to cost less than $50 million over five years. A negative cost means that a provision is a negative tax expenditure, which raises revenue. The JCT defines negative tax expenditures as “tax provisions that provide treatment less favorable than normal income tax law and are not related directly to progressivity.” Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2017-2021.”

|

|

Therapeutic research credit

|

$0.1 |

|

Special rule to implement electric transmission restructuring

|

-$0.2 |

|

Reduced rates on first $10 million of corporate taxable income

|

$3.1 |

|

Net alternative minimum tax attributable to net operating loss limitation

|

-$0.4 |

|

50 percent tax credit for certain expenditures for maintaining railroad tracks

|

$0.2 |

As with individual tax expenditures, some of the above provisions, such as the railroad track maintenance credit, are extenders. Though scheduled to expire according to current law, they are likely to be retroactively extended for the 2018 tax year.[18]

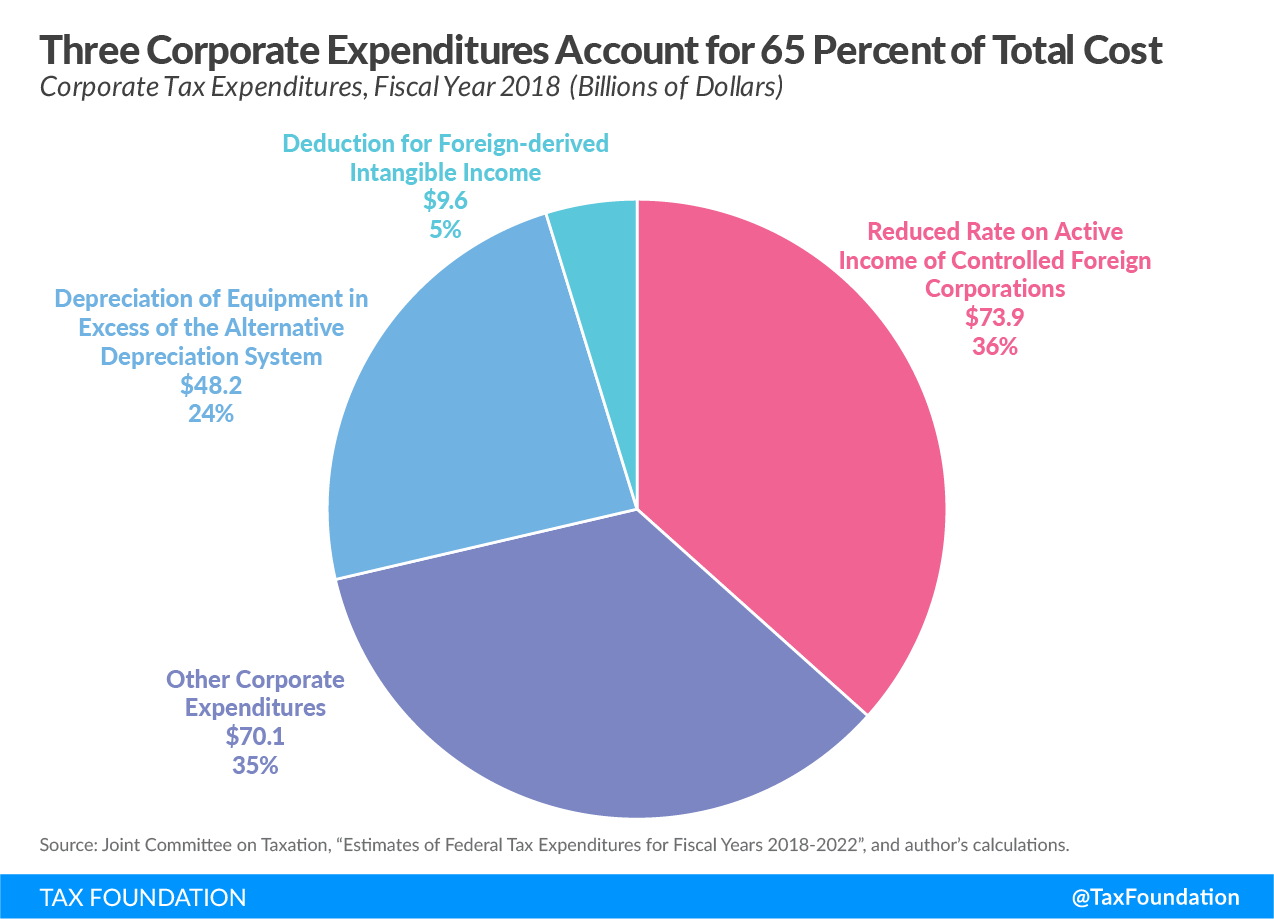

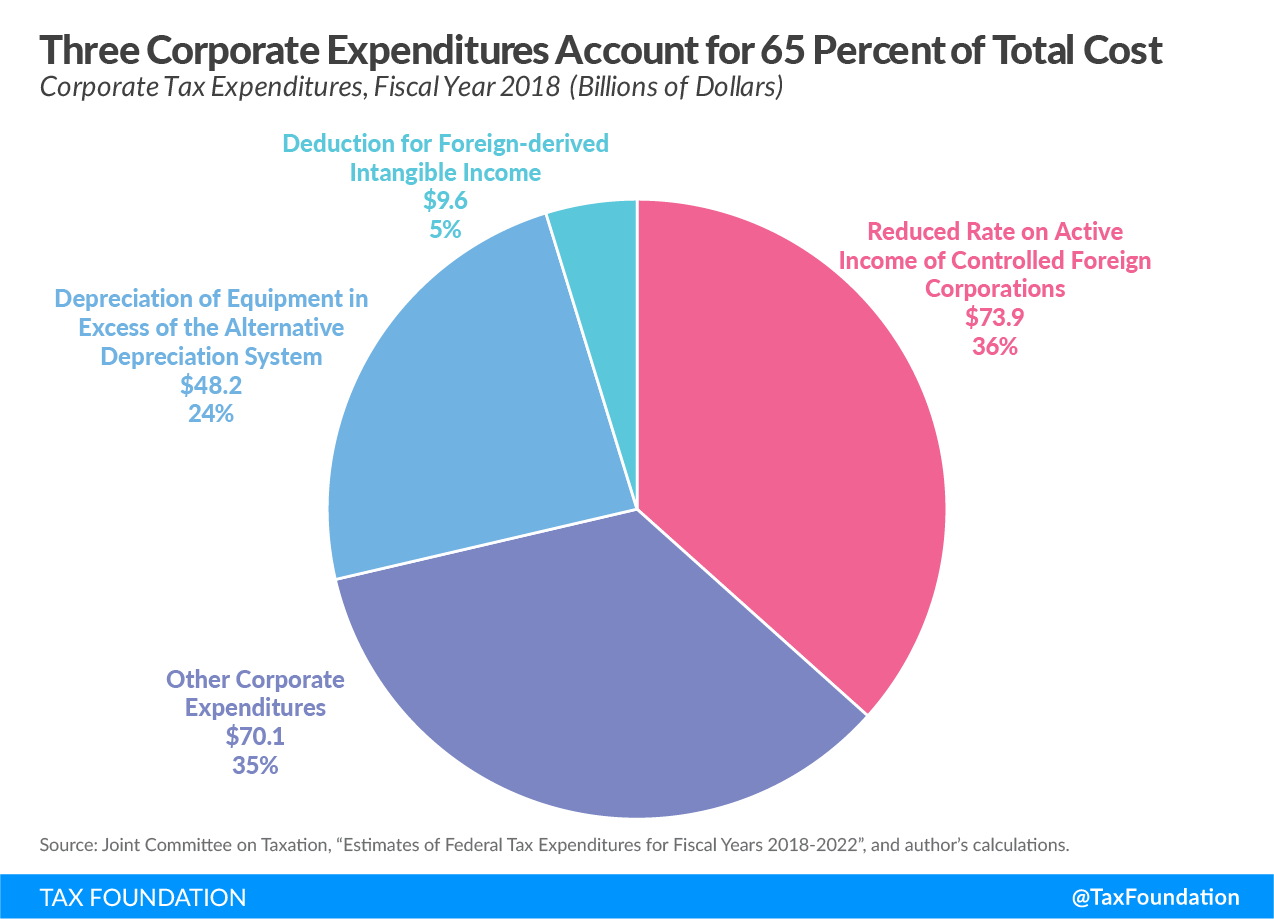

Figure 4 illustrates the largest corporate tax expenditures for fiscal year 2018. Together, the reduced tax rate on active income of controlled foreign corporations, depreciation of equipment in excess of the alternative depreciation system, and deduction for foreign-derived intangible income derived from trade or business within the U.S. make up approximately 65 percent of all corporate tax expenditures. In total, corporate tax expenditures are projected to cost $201.8 billion in 2018.

Figure 4

Reduced Tax Rate on Active Income of Controlled Foreign Corporations ($73.9 billion)

Before the TCJA was passed, active foreign income was usually taxed upon repatriation. Now, global intangible low-tax income (GILTI) is taxed currently, even if it is not distributed. This expenditure provides a 50 percent deduction to U.S. corporations on their GILTI. Some active income is now excluded from tax, and distributions from active income are now not taxed upon repatriation.[19] GILTI is a broad change to the tax code intended to reduce the incentive to shift corporate profits out of the U.S. by using intellectual property.

Depreciation of Equipment in Excess of the Alternative Depreciation System ($48.2 billion)

The costs of equipment and machinery are typically depreciated over time to match the reduction in economic value as equipment wears down and becomes obsolete. Depreciation of equipment ensures that net income from the property is measured appropriately each year. This expenditure provides accelerated deductions relative to economic depreciation.[20]

There is a better way to go forward. While depreciation is a useful accounting concept to calculate book values of corporations, the economic costs of an asset should be reflected by expensing; that is, the cost of the asset should be deductible in the year that the money is actually spent, properly reflecting the time value of money.[21] This is the sort of deduction that business transfer taxes or value-added taxes use, and it is in many respects much more normal than anything that the U.S. has used in the past few decades.[22]

Deduction for Foreign-derived Intangible Income Derived from Trade or Business Within the U.S. ($9.6 billion)

Income earned by U.S. corporations from foreign markets would typically be taxed at the full U.S. rate. This expenditure provides a deduction worth 37.5 percent of foreign-derived intangible income (FDII). In 2026, the deduction will fall to 21.875 percent.[23]

In combination, GILTI and FDII can be thought of as a worldwide tax on deemed intangible income. They are meant to reduce incentives for companies to move the location of intellectual property to shift corporate profits out of the U.S.

Under the taxation of GILTI and FDII, U.S.-based multinational companies face roughly the same tax rate on intangibles used in serving foreign markets regardless of where those intangibles are located. If intellectual property is located in a foreign market and is used to sell products to foreign customers, it faces a minimum tax rate of between 10.5 percent and 13.125 percent through GILTI. If that same intellectual property is located in the United States and is used to sell products to those same foreign customers, it faces a tax rate of 13.125 percent through FDII.

The idea behind a regime including FDII and GILTI is that they are a carrot and a stick that encourages companies to place profits and intellectual property in the United States.

Corporate Tax Expenditures Set to Expire in 2019

Table 6 lists the five corporate tax expenditures that are scheduled to expire at the end of 2018.

Table 6. Corporate Tax Expenditures Scheduled to Expire at the End of 2018

| Expenditure |

2018 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022.”

|

|

Inventory property sales source rule exception

|

$0.5 |

|

Expensing of costs to remove architectural and transportation barriers to the handicapped and elderly

|

N/A |

|

Deduction for income attributable to domestic production activities

|

$3.3 |

|

Credit for Indian reservation employment

|

N/A |

|

District of Columbia tax incentives

|

N/A |

|

Note: JCT does not provide specific estimates for provisions that are estimated to cost less than $50 million over five years.

|

Thus, according to current law, there will be 120 corporate tax expenditures in fiscal year 2019, compared to 121 in 2017. As with individual tax expenditures, however, these estimates likely underestimate both the number and the cost of expenditures for 2019 because they do not account for the probable reauthorization of extenders.

Figure 5

The Number of Tax Expenditures Following Tax Reform

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was the first large-scale reform to the federal tax code in a generation. The law lowered tax rates for individuals and corporations and included some simplifications to the associated tax bases. For instance, the standard deduction for individuals was nearly doubled to $12,000 for individuals and $24,000 for married couples filing jointly in 2018. This increased the number of individuals itemizing from approximately 70 percent of filers to approximately 90 percent of filers, reducing compliance costs by $3 billion to $5 billion.[24]

However, as shown in Figure 6 below, the reforms did not reduce the number of total tax expenditures. In fact, the number of tax expenditures in 2018 is higher than it was in 2017 for both the individual and corporate tax codes. Ideally, in future tax reform efforts, Congress will work to eliminate tax expenditures.

Figure 6

Conclusion

As of 2018, the tax code has 173 individual tax expenditures and 125 corporate tax expenditures, with a projected cost of $1.5 trillion in 2018. Many expenditures are cases of preferential treatment for particular economic activities and therefore do not belong in the tax code. However, other expenditures play a broader and more valuable role by moving the U.S. towards another tax system. Simply eliminating expenditures across the board would therefore be misguided.