by r Hampton | Mar 21, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Income Tax Credits Paired with Numerous Tax Increases in Wisconsin Gov. Evers’ Budget

With the release of his first biennial budget, introduced as Senate Bill 59, Wisconsin’s new Governor Tony Evers (D) has proposed dozens of miscellaneous tax changes. While the budget offers targeted income tax cuts for certain low- and middle-income taxpayers, these cuts are far outweighed by tax increases elsewhere, such as business taxes and excise taxes. Taken as a whole, these changes would make Wisconsin’s tax code more complex and less neutral, missing an opportunity to provide tax relief within the context of pro-growth structural reform.

Individual Income Tax Changes

The most notable of the proposed individual income tax changes is the creation of a credit to reduce tax liability for individuals making less than $100,000 and families making less than $150,000. This proposal comes as no surprise, as Gov. Evers campaigned on a 10 percent tax cut for taxpayers with income below those thresholds, but the budget provides new details about the credit’s structure.

Under the proposal, a “Family and Individual Reinvestment” or “FAIR” credit would be available only to taxpayers with Wisconsin adjusted gross income (WAGI) below $100,000 (single filers) or $150,000 (married filing jointly). This nonrefundable credit would be claimed after most other credits are applied, reducing tax liability by 10 percent or $100 ($50 for married taxpayers filing separately), whichever is greater. This credit would begin to phase out once income reaches $80,000 (single filers) or $125,000 (married filers), phasing out completely at $100,000 and $150,000, respectively. Expected to cost $833.5 million over two years, this credit would become Wisconsin’s second-largest individual income tax credit after the School Property Tax Credit.

The budget also proposes increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Currently, Wisconsin taxpayers who are eligible to claim the federal EITC may claim a percentage of the federal credit against their state tax liability. The refundable state credit is offered at 4 percent for families with one child, 11 percent for families with two children, and 34 percent for families with three or more children. The governor’s proposal would increase the credit to 11 percent for families with one child and 14 percent for families with two children, while keeping it at 34 percent for families with three or more children.

Further, the budget would create a new child and dependent care credit in lieu of Wisconsin’s existing “subtraction for child and dependent care expenses.” Taxpayers eligible for the federal child and dependent care tax credit would be eligible to claim 50 percent of the same amount on their Wisconsin tax return.

Beyond that, the governor’s budget would replace a scheduled across-the-board income tax rate reduction with a rate reduction to the lowest bracket only. Following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., Wisconsin began requiring online retailers to collect and remit Wisconsin’s sales tax. In December 2018, Act 368 was signed into law, allocating any increased revenue from “out-of-state retailers” collected between October 1, 2018 and September 30, 2019 to across-the-board individual income tax rate reductions. The Wisconsin Department of Revenue has projected an estimated $60 million increase in online sales tax collections during that period, which would allow for a 0.04 percentage point rate reduction to each of Wisconsin’s four marginal income tax rates in tax year 2019. However, the governor’s budget proposes changing that law so only the 4 percent income tax rate, which applies to only the first $11,760 in marginal taxable income, would be reduced.

Finally, the budget proposes changes to the tax treatment of capital gains. Wisconsin’s tax code allows a 30 percent deduction on net capital gains for assets held for more than one year (for farm assets, it’s 60 percent of net capital gains). This income is excluded from a taxpayer’s capital gains tax basis to help ensure investors are taxed on their real gains, not their nominal gains. This exclusion is currently available to all investors, but the governor’s proposal would limit the exclusion so it can only be claimed on capital gains income when a taxpayer’s combined noncapital gains income and capital gains income is below $100,000 (single filers) or $150,000 (married filers).

The aforementioned changes would provide income tax relief to low- and middle-income taxpayers, but would do so by narrowing the tax base, making the tax code less neutral, and adding unnecessary complexity to the income tax system. It’s important to keep in mind that Wisconsin already offers numerous income tax credits and deductions to provide targeted tax relief to low- and middle-income residents. Provisions like the refundable EITC and refundable homestead credit allow many lower-income Wisconsin residents to receive a net income tax refund. The sliding-scale standard deduction, available only to those with incomes less than $103,500 (single) or $121,009 (married), reduced tax collections by $857 million in FY 2018. With provisions like these already exclusively benefiting low- and middle-income residents, the introduction of a new credit into the mix would be duplicative and further complicate tax filing. A simpler, more neutral approach to individual income tax relief would be to reduce tax rates within the existing framework, or better yet, reduce tax rates while creating a more growth-friendly tax structure.

Business Tax Changes

The governor’s budget includes tax changes that would impact businesses in certain industries. Specifically, the proposal would make the nonrefundable Manufacturing and Agriculture Credit (MAC) less generous while making the refundable Research Credit more generous.

Wisconsin’s MAC is a nonrefundable credit available to pass-through businesses and traditional corporations and can be claimed in an amount equal to 7.5 percent of income derived from manufacturing or agricultural activities, not to exceed a business’s total tax liability. In the governor’s proposal, the credit for manufacturers could be claimed against only the first $300,000 in income derived from manufacturing activities in a year. However, the proposal would not impose a cap on the amount of the credit that can be claimed by agricultural producers. Capping the manufacturing portion of the MAC would increase taxes on manufacturers by an estimated $516.6 million over two years.

Meanwhile, the proposal would make Wisconsin’s refundable Research Credit more generous. Currently, this credit can be claimed on amounts equal to 11.5 percent of a taxpayer’s expenses related to research and development activities in Wisconsin. If the credit amount exceeds tax liability, a tax refund can be claimed in amounts up to 10 percent of the total credit value. Under the governor’s proposal, the refundable portion of the credit would be increased so claimants could receive a refund up to 20 percent, rather than 10 percent, of the credit value.

These tax changes would further accentuate the unequal tax treatment of different industries under Wisconsin’s income tax laws. Instead, policymakers ought to consider how Wisconsin’s high corporate and individual income tax rates detract from the state’s attractiveness as a location for business investment. Ultimately, broad-based, low-rate taxes create the most favorable environment for business investment and growth across all industries.

Sales Tax Changes

Also included in the budget is a proposal to subject two new business inputs to the sales tax. An ideal sales tax system excludes business inputs, not to give businesses a special tax break, but to prevent tax pyramiding. When business inputs are subject to the sales tax, the costs of production rise, and much of the intrinsic sales tax burden gets passed along to consumers in the form of higher retail prices. Wisconsin already properly excludes most business inputs from the sales tax, so handpicking certain inputs for taxation would be a step in the wrong direction.

Further, this proposal would require online marketplace facilitators to collect and remit sales taxes on behalf of third-party sellers who use these platforms to connect with customers. Current Wisconsin law requires remote sellers who make $100,000 worth of sales or 200 transactions in-state to collect sales taxes from buyers and remit those taxes to the state. The purposes of this de minimis threshold is to allow a safe harbor for remote sellers making only occasional sales in a state.. In instances in which sales tax is not collected at the point of sale, the consumer is responsible for calculating the sales tax owed and remitting that amount to the state. Unsurprisingly, compliance is notoriously low, as many consumers assume a sales tax is only owed when collected at the point of sale. Several states have enacted laws requiring marketplace facilitators to collect sales taxes as a way to boost compliance with state sales and use tax laws. The governor’s budget estimates this would increase collection of taxes already owed by $93.9 million over two years.

Marijuana, Tobacco, and Vapor Tax Changes

Governor Evers’ proposal also includes changes to various excise taxes, including taxes on tobacco, vapor, and medical marijuana products.

Currently, Wisconsin’s cigarette tax is 12.6 cents per cigarette, or $2.52 for a pack of 20., the 12th highest cigarette tax in the country. Other tobacco products, like chewing tobacco, are generally taxed at 71 percent of the manufacturer’s list price. The governor’s budget proposes imposing taxes on e-cigarettes and vapor products at 71 percent of the manufacturer’s list price, regardless of whether said vapor products contain nicotine. Under this proposal, Wisconsin would follow Minnesota and the District of Columbia in having one of the highest vapor taxes in the country.

The governor’s proposal would also raise additional revenue by taxing “little cigars” like cigarettes, and by creating a medical marijuana program, with sales taxes and a 10 percent excise tax levied on medical marijuana.

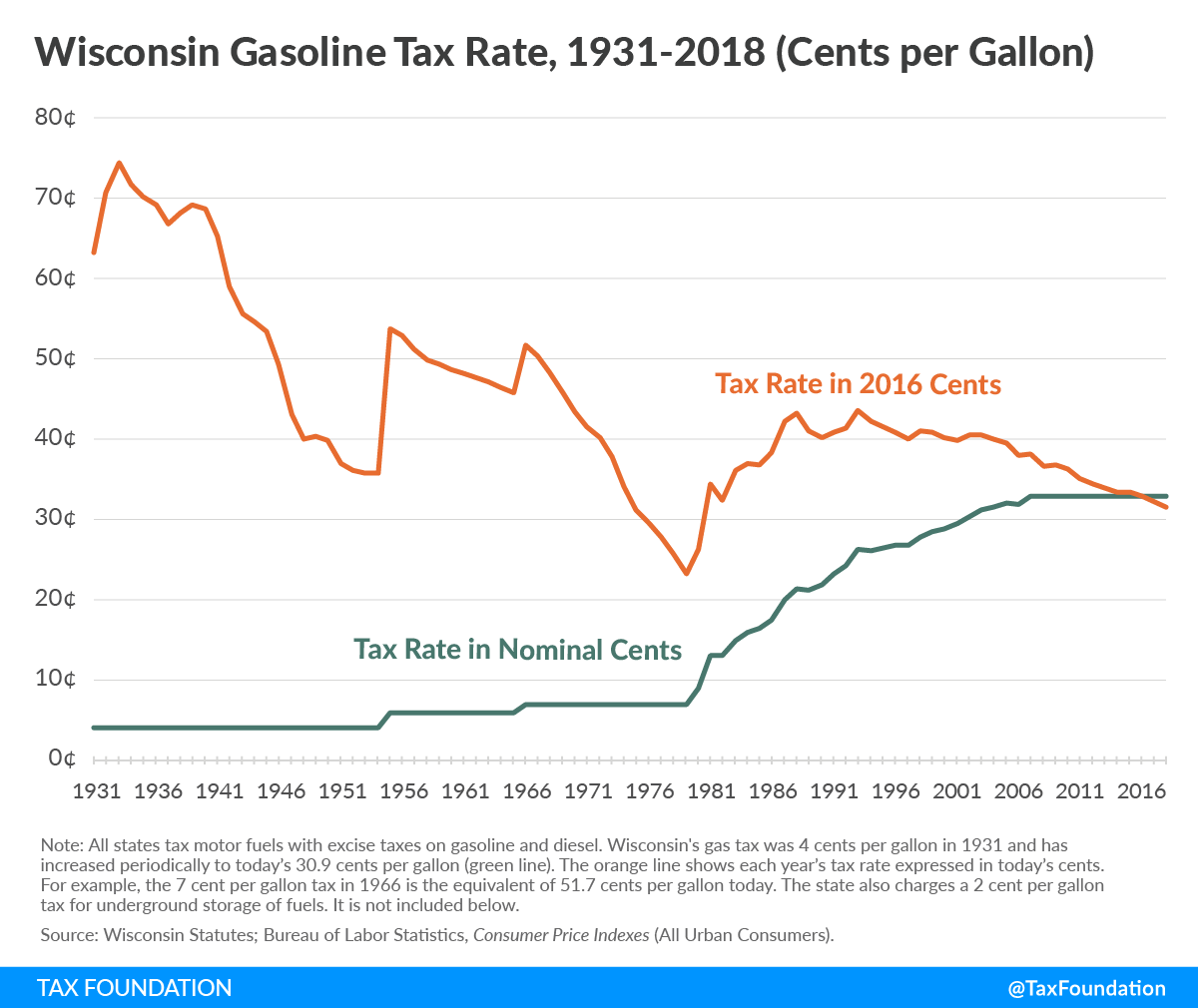

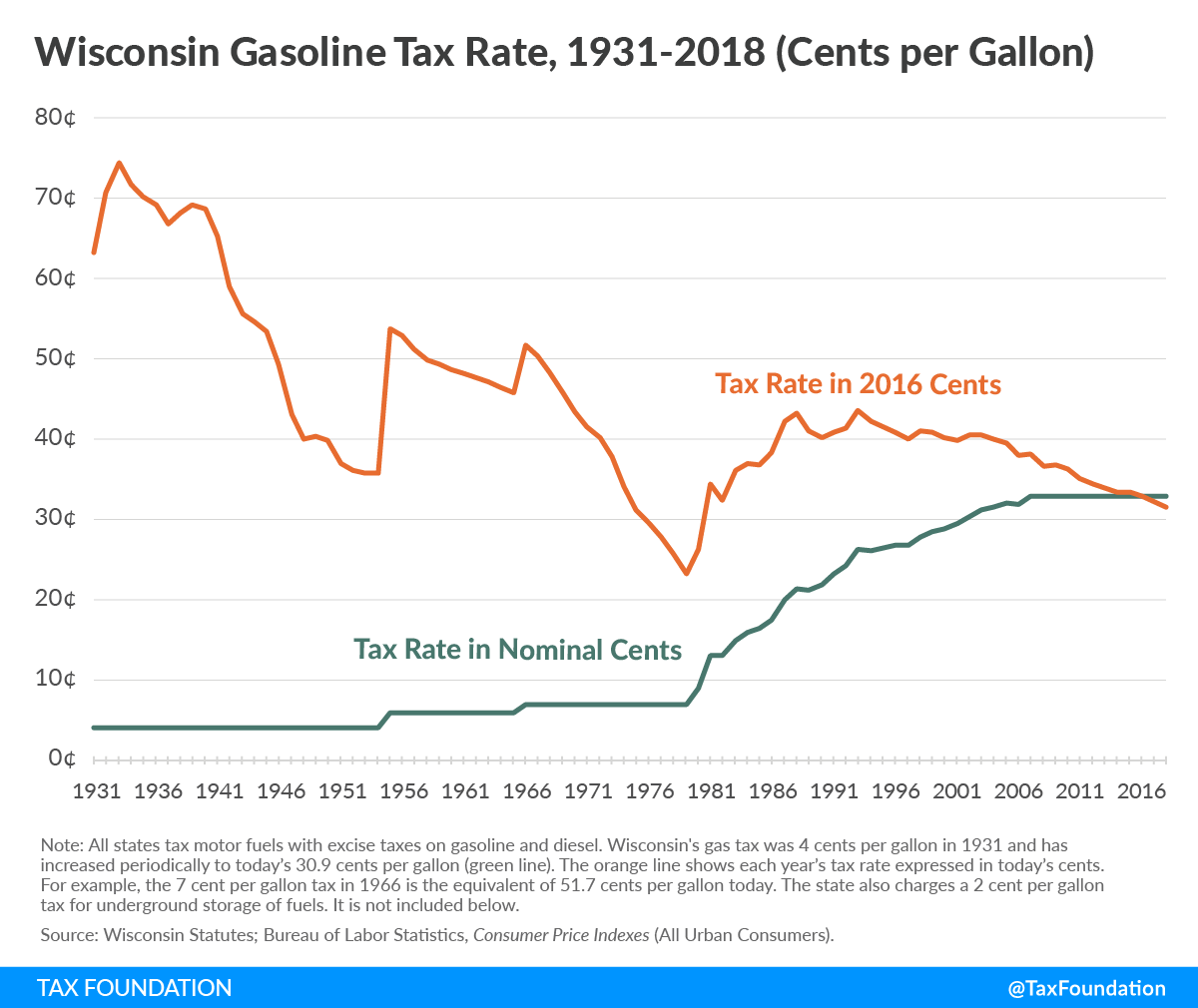

Transportation Tax Changes

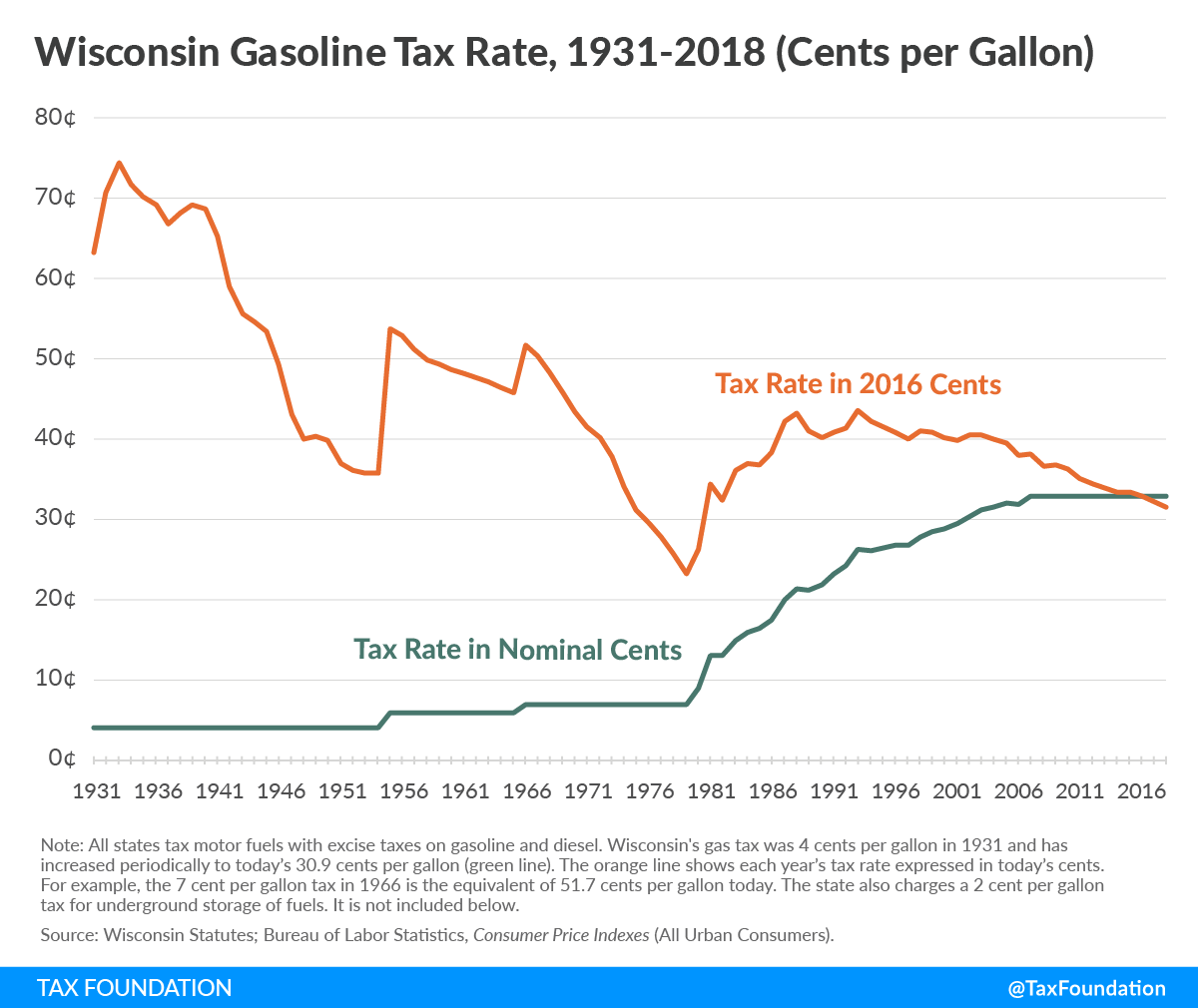

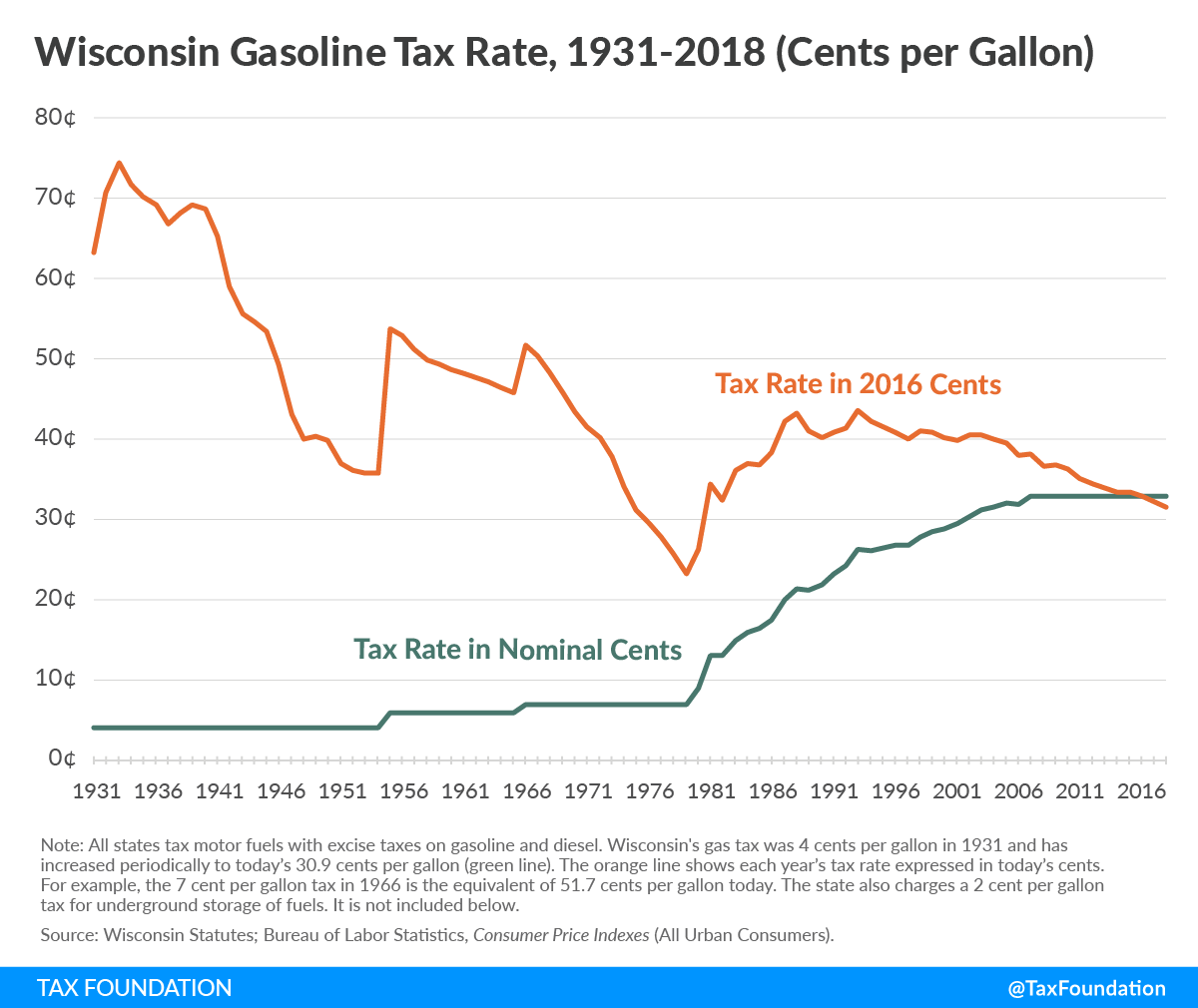

The governor’s transportation tax proposals would put a greater emphasis on user taxes and fees while reducing reliance on general tax revenue to fund transportation. Most notably, the plan would increase the gas tax by 8 cents per gallon and begin indexing it for inflation. Currently, the state-levied gas tax totals 32.9 cents per gallon (cpg), including a 30.9 cpg excise tax and a 2 cpg tax on underground storage of fuels. Wisconsin’s 32.9 cpg gas tax has remained constant since 2006, but the value of the tax has declined in real terms every year since 2003. Additionally, as vehicles become more fuel-efficient, fewer gallons of gas are needed to travel the same distance, further eroding the value of the gas tax.

To offset some of the gas tax increase, the governor’s proposal would eliminate the minimum markup on motor fuels. Currently, Wisconsin’s minimum markup law requires gasoline retailers to raise the price of gasoline 9.18 percent above the wholesale price. This Depression-era law was originally designed to prevent retailers from using predatory pricing to defeat their competitors and gain a monopoly, but there is little evidence price gouging would occur absent a minimum markup law.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Income Tax Credits Paired with Numerous Tax Increases in Wisconsin Gov. Evers’ Budget

by r Hampton | Mar 21, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Tax Treatment of Worker Training

Key Findings

- Education and training are investments in human capital and, over time, increase productivity and economic growth as human capital accumulates.

- Research shows that human capital investment and accumulation leads to widespread economic gains for individuals, firms, and economies.

- Tax treatment affects decisions to invest in human capital and can lead to distortions in the decision-making process for both firms and individuals. Currently, firms and individuals can deduct certain types and amounts of human capital investments, while individuals have access to some tax credits.

- Several proposals exist to expand the deductibility of, or even to subsidize, human capital investments. Many of these proposals point to factors such as positive externalities and the skills gap as reasons to improve tax treatment.

- Lawmakers ought to consider streamlining or consolidating existing provisions, and strive to make new proposals simple, efficient, easy to administer, and neutral.

Introduction

Education and training are investments in human capital that can increase productivity over time, similar to the way investments in physical capital, such as machinery and equipment, can increase productivity. However, while physical capital accumulation can occur quickly, human capital accumulation occurs over a longer period.[1]

The tax treatment of different types of investments, such as those in research and development (R&D), physical capital, and human capital, varies. R&D expenses are immediately deductible and eligible for tax credits. Many physical capital investments are immediately deductible. Only certain categories of human capital investments are deductible for firms and individuals, and some credits are available for individuals.

Currently, employers can deduct certain qualified education and training expenses for tax purposes, and certain qualified educational benefits are excludable from the taxable portion of employees’ wages. Generally, at the firm level, only education expenses which improve worker skills for their current positions are deductible. If the education would qualify workers for a new type of work, the expenses are not deductible. At the individual level, the tax treatment of educational expenses varies by income level and type of education.

These differences are important because tax treatment is relevant to human capital investment decisions,[2] and human capital accumulation is a key driver of economic growth.[3] Differing tax treatment can distort costs of investments and decision-making by firms and individuals.

Several proposals exist to expand the deductibility of education and training expenses and to subsidize these expenditures by creating a tax credit. These proposals should be evaluated in the context of neutrality, externalities, and other policies which affect education and training.[4]

This paper reviews background information about human capital investment, how taxation affects human capital decisions, tax treatment across various jurisdictions, and proposals which would change the tax treatment of human capital investment in the United States.

Background on human capital investment

Human capital investment and accumulation leads to widespread gains for individuals, firms, and economies; however, as noted earlier, human capital accumulation does not occur quickly. The amount that a company spends on education and training can be thought of as a form of investment.

Under a neutral tax system, all investment expenses would be immediately deductible, including business investment in worker education and training and individuals’ investments in their own education.[5] Thus the correct tax treatment for human capital investment is deducting the training expenses and taxing the higher income levels that accrue due to training.

Workers with higher levels of educational attainment tend to earn higher wages and experience lower rates of unemployment. For example, in 2017, the unemployment rate and median usual weekly earnings across all workers was 3.6 percent and $907, respectively; for workers with a bachelor’s degree, these were 2.5 percent and $1,173, respectively.[6] Employer-supported training has benefits for employees and firms: it can raise employees’ wages or improve their job stability, and increase firm productivity or decrease turnover.[7]

Similarly, employer-provided training, whether formal or informal, has been shown to have positive effects on worker productivity and wages. In one study, hours of training were shown to be positively related to productivity and wage growth; the effects of formal training were much larger than those for informal training.[8] Likewise, formal training has a positive effect on labor productivity.[9]

While this evidence shows the benefits of educational attainment and worker training at the individual level, there are also benefits to firms. For example, formal employee training programs can bring below-average firms up to the performance level of comparable businesses.[10]

However, some research indicates there may be underinvestment in human capital which contributes to the so-called skills gap. One reason why firms may underinvest is due to the public good component of training. For example, if Company A trained a worker in a skill, that could increase the return to all companies if the skill was transferable. To the extent that the skills obtained by training would be transferable to competitors, firms may underprovide training.

Workers in many industries need to regularly update their skills as the constant development of new technologies and processes results in new methods of production.[11] For example, by 2020, more than one-third of the core skill sets of most occupations will be skills that are not considered crucial to today’s workforce.[12] These rapid changes indicate a need for continual training.[13]

Recent survey data confirms that firms acknowledge employees lack needed skills; however, it also shows that these same firms are not investing in training programs in a significant way.[14] It seems likely that employers are underinvesting in worker training for several reasons. Firms may have a lower incentive to provide worker training as employees accrue most of the gains from training, which results in increased bargaining power, and because employees can leave for or be poached by competitors.[15]

Some evidence suggests human capital may have positive externalities; that is, an individual’s human capital accumulation may provide benefits to others, or society at large. Externalities may occur through several channels, such as enhancing the productivity of others, reducing criminal behavior, or improving social cohesion—however, some studies suggest that empirical evidence for positive externalities is weak.[16] This may be because the benefits of education are internalized by individuals or firms in the form of higher returns.

One policy change that may aide employers in recouping the costs of training would be to change its tax treatment.[17] And, given the evidence that employers may be underinvesting in worker training and that there may be positive externalities to training, there may be justification to subsidize worker training beyond allowing deductibility for expenses. However, when weighing these considerations, policymakers should consider the broader context of all worker training and education-related policies, not just tax policy: [18]

Solutions that directly tackle market failures or distortive institutional labor market settings that result in human capital underinvestment are generally more efficient than fiscal solutions, such as tax incentives or public subsidies. However, direct solutions may not always be feasible, for example due to political considerations or due to the nature of human capital (e.g., it cannot be used as collateral). Under these circumstances, fiscal incentives may provide a second-best solution.

How taxation affects human capital investment decisions

The decision about whether to invest in education or training depends on the cost and the expected return of a given investment choice. Numerous factors can affect both the cost and the expected return, including taxation.

An OECD report entitled “Taxes and Investment in Skills” outlines seven channels through which taxes impact the incentive to invest in skills formation:[19]

(1) the tax treatment of the direct costs (e.g., tuition fees), (2) the tax treatment of savings (or equity), debt, income and fringe benefits (e.g., employer-paid training) used to finance the investment, (3) the (notional) tax treatment of foregone earnings or profits, (4) the (notional) tax treatment of foregone capital income, (5) the tax treatment of gross financial benefits (higher earnings for individuals and higher profits for employers), (6) tax features that provide insurance against the uncertainty of investment returns, and (7) earmarked taxes on employers or tax-like mechanisms that ensure a minimum level of investment in training.

Various tax policies can have opposing effects on human capital investment decisions, and other government or fiscal policies can also affect these decisions.[20]

Tax treatment in the United States

Generally, in the United States, businesses can deduct most training expenses; certain employer-provided education assistance is excluded from employee wages; and individuals may access a variety of education-related tax provisions.

According to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “Ordinary and necessary expenses paid for the cost of the education and training of your employees are deductible.” However, if the expenses are for training that helps the individual to meet minimum requirements of their present trade or business or qualify an individual for a new trade or business, they are not deductible.[21]

If a business pays for or reimburses an employee’s education expenses as part of a qualified educational assistance program, the payments are deductible. Additionally, businesses can exclude up to $5,250 of educational assistance from an employee’s wages if the expenses occur under a qualified educational assistance program. If the business does not have an educational assistance plan,[22] or if the assistance exceeds $5,250, it must be included in wages unless the benefits are working condition benefits.

The IRS explains how training can qualify as working condition benefits in Publication 15-B:[23]

To qualify, the education must meet the same requirements that would apply for determining whether the employee could deduct the expenses had the employee paid the expenses. Degree programs as a whole don’t necessarily qualify as a working condition benefit. Each course in the program must be evaluated individually for qualification as a working condition benefit. The education must meet at least one of the following tests.

- The education is required by the employer or by law for the employee to keep his or her present salary, status, or job. The required education must serve a bona fide business purpose of the employer.

- The education maintains or improves skills needed in the job.

However, even if the education meets one or both of the above tests, it isn’t qualifying education if it:

- Is needed to meet the minimum educational requirements of the employee’s present trade or business, or

- Is part of a program of study that will qualify the employee for a new trade or business.

Individual taxpayers may access a variety of credits, deductions, exclusions, and savings plans for higher education. Most of these provisions apply to only undergraduate and graduate programs, though one tax credit, the Lifetime Learning Credit, may be used for qualifying expenses including jobs skills courses.[24]

The progressivity of the individual income tax can also impact individual decisions to pursue human capital investments, as these depend in part on the expected return to that investment. Higher marginal tax rates can discourage long-run decisions to invest in education or improve skills.[25]

Tax treatment across the OECD

As of 2011, 16 countries, including the United States, provide personal income tax relief for work-related professional training. Like the U.S., many countries restrict tax relief to expenses on training directly related to the taxpayer’s current employment or job, while only two, Austria and Germany, provide tax relief for training which prepares the taxpayer for a new occupation.[26] However, types of training and education which qualify vary across the 16 countries.

Corporate income tax treatment across OECD countries is less varied; in 32 countries, training expenditures are generally deductible in the year they occur. Some countries provide additional tax credits or enhanced deductions for the costs of employee training. Twenty-two of the OECD countries, including the U.S., impose restrictions that require expenses to be related to the business activity of the firm to be deductible.

Proposals to change the tax treatment

Lawmakers and others have suggested several ways to improve the tax treatment of worker training in order to encourage additional investment.

One idea is to create a Worker Training Tax Credit, which would be similar in design to the Research and Development Tax Credit.[27] A proposal from the Aspen Institute suggests structuring the credit as 20 percent of the difference between an established base level of training expenditures and current year expenditures, allowing small and new businesses to use the credit to offset payroll tax liability.[28] A handful of states utilize similar tax incentives for worker training, ranging from 5 percent to 50 percent of training expenses.[29]

Another policy change would be to allow businesses to deduct all forms of worker training, including those which would qualify individuals for a new position, rather than limiting it to certain types of training or certain degree programs.[30] For example, Caleb Watney discusses deductibility in the context of worker shortages in the artificial intelligence field:[31]

Employers may currently deduct a portion of the costs of worker training as long as it is to improve productivity in a role they already occupy, but…employers may not deduct the costs if it would qualify them for a new trade or business. Expanding this deduction—both in size and scope—so that the full cost of worker training for new trades could be deducted would incentivize more investment in building the AI workforce that is needed to fuel our economy. Given the pre-existing level of interest by employers in this strategy, it seems likely this could become a fruitful part of our domestic AI pipeline, if given more support.

Proposals to change the tax treatment for individuals exist as well. Most recently, Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Ben Sasse (R-NE) introduced Senate Bill 275, which would provide lifelong learning accounts to pay for education expenses including skills training, apprenticeships, and professional development.[32]

Evaluating proposals

Any proposed change should be evaluated according to the following principles: simplicity, administrability, neutrality, and efficiency.

Simplicity and Administrability

Currently, the tax code is complex and riddled with various provisions designed to promote certain activities or investments. For example, the tax code already contains at least a dozen tax-neutral savings accounts, each with their own rules and restrictions. The creation of an additional tax-neutral savings account for individuals, for example, would add to the tax code’s complexity. Rather than adding to that complexity, solutions that would streamline savings options for taxpayers, such as universal savings accounts, should be considered.

Similar arguments apply to the addition of new tax credits. Currently, individual taxpayers can choose from a complex swath of education-related provisions, which leads to suboptimal utilization. On the business side, the existing R&D credit is complex and difficult to parse, which provides an advantage to larger companies that have the resources to devote to legal barriers and leads to wasteful administrative expenditures.[33] Lawmakers ought to evaluate whether additional credits, either for individuals or businesses, would add to the complexity under current law.

Another factor to consider when adding new policies is program administrability. The Internal Revenue Service is not designed to be a benefits administrator, but rather to collect taxes. Enforcement and verification of taxpayer information, such as whether they obtained qualifying education, can be difficult.

Neutrality

Lawmakers should provide neutral tax treatment to all types of investment. This means that expensing provisions should not favor one type of training or education over another, nor one type of capital over another.

Efficiency

While many of the current provisions were designed to increase educational attainment or improve the affordability of higher education, evidence suggests that they are not effectively accomplishing those goals.[34] For this reason, new proposals that mirror the structure of current policies should be approached with skepticism. While the intent of a new tax credit or other provision may be positive, the provision may not work as intended.

Lawmakers should avoid using the tax code to encourage or discourage certain behaviors, as it is rarely an efficient tool for doing so. Instead, lawmakers should focus on making the tax code neutral, as mentioned above, so tax-induced distortions do not lead to an inefficient allocation of resources.

Conclusion

Human capital accumulation, the result of investments in worker training and education, is a key driver of economic growth in the long run. Tax treatment is one factor that influences decisions to invest in worker training and education. Currently, the tax code allows certain categories of human capital investment to be deducted, while credits are available for others. However, deductibility is rather limited, and provisions available to individuals are underutilized, complex, and inefficient.

When considering policies which would change the tax treatment of human capital investment, it’s important for lawmakers to properly account for externalities, neutrality, and interactions with the broader swath of education and training policies already in place. Rather than approaching the tax treatment of worker training in a piecemeal fashion, lawmakers should consider the entire scope of federal policies which relate to human capital investment, including tax rates, credits, deductions, savings plans, and non-fiscal-related policies. Consolidation of overlapping provisions would improve simplicity and administrability. The existing tax treatment of human capital is nonneutral, and reform efforts should work to resolve this. Ideally, all forms of investments should be immediately deductible, while arguments for subsidies should be further examined.

Notes

[1] Robert J. Barro, “Human Capital and Economic Growth,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 1992, 204, https://www.kansascityfed.org/publicat/sympos/1992/s92barro.pdf.

[2] Carolina Torres, “Taxes and Investment in Skills,” OECD Publishing, Sept. 17, 2012, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5k92sn0qv5mp-en.pdf?expires=1541711985&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=9A12B5C137E1092337D6CEDB684135C5.

[3] Rui Costa, Nikhil Datta, Stephen Machin, and Sandra McNally, “Investing in People: The Case for Human Capital Tax Credits,” Centre for Economic Performance, February 2018, http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/is01.pdf.

[4] Note that the federal government administers 47 job training programs (as of 2011). This paper does not specifically address these programs; however, at least some research indicates they may not be an effective way to boost wages or create jobs. Deductibility at the firm level for human capital investment is likely a better alternative. See Matthew D. Mitchell and Tamara Winter, “Helping Displaced Workers without Corporate Welfare,” Mercatus Center, May 2, 2018, https://www.mercatus.org/bridge/commentary/helping-displaced-workers-without-corporate-welfare.

[5] If portions of education-related expenditures represent consumption, rather than investment, then deductibility would not be the appropriate tax treatment. See Erica York, “Evaluating Education Tax Provisions,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 20, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/education-tax-provisions/ and Gerald Prante, “Education Tax “Subsidies” – Justified or Not?” Tax Foundation, May 13, 2008, https://taxfoundation.org/education-tax-subsidies-justified-or-not/.

[6] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Projections, March 27, 2018, https://www.bls.gov/emp/chart-unemployment-earnings-education.htm.

[7] Linda Levine, “Employer-Provided Training,” Congressional Research Service, May 3, 2000, http://congressionalresearch.com/RL30546/document.php?study=EMPLOYER-PROVIDED+TRAINING.

[8] Harry J. Holzer, “The Determinants of Employee Productivity and Earnings: Some New Evidence,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 2782, December 1988.

[9] Ann P. Bartel, “Formal Employee Training Program and Their Impact on Labor Productivity: Evidence From a Human Resources Survey,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 3026, July 1989.

[10] Ann P. Bartel, “Productivity Gains from the Implementation of Employee Training Programs,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 3893, November 1991, 18.

[11] Michael D. Farren, “Bridging the Skills Gap,” Testimony before the House Small Business Committee, Subcommittee on Economic Growth, Tax, and Capital Access: Examining the Small Business Labor Market, Sept. 7, 2017, 4, https://www.mercatus.org/publications/bridging-skills-gap.

[12] World Economic Forum, “The Future of Jobs,” January 2016, 3, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_FOJ_Executive_Summary_Jobs.pdf.

[13] Some may contest the skills gap argument; for example, see Andrew Weaver, “The Myth of the Skills Gap,” MIT Technology Review, Aug. 25, 2017, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/608707/the-myth-of-the-skills-gap/. However, regardless of disagreement over the skills gap, worker training remains important, as does communication between businesses and workers about what training is needed.

[14] Udemy, “Companies See Widespread Skills Gaps, But Most Spend Minimally On Training,” March 26, 2015, https://about.udemy.com/press-releases/companies-see-widespread-skills-gaps-but-most-spend-minimally-on-training/.

[15] Carolina Torres, “Taxes and Investment in Skills,” 11.

[16] Fabian Lange and Robert Topel, “The Social Value of Education and Human Capital,” Revised Sept. 2004, 2-3, https://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Workshops-Seminars/Labor-Public/lange-041105.pdf.

[17] Caleb Watney, “Reducing Entry Barriers in the Development and Application of AI,” R Street, Oct. 9, 2018.

[18] Carolina Torres, “Taxes and Investment in Skills,” 8.

[19] Ibid., 6.

[20] Ibid., 10.

[21] Internal Revenue Service, Publication 535, “Business Expenses,” 2017, https://www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-publication-535.

[22] For requirements for a qualifying program see Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, “26 CFR § 1.127-2 – Qualified educational assistance program,” https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/26/1.127-2.

[23] Internal Revenue Service, Publication 15-B, “Employer’s Tax Guide to Fringe Benefits,” 2017, https://www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-publication-15-b.

[24] See Erica York, “Evaluating Education Tax Provisions,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 20, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/education-tax-provisions/.

[25] Garrett Watson, “Ocasio-Cortez’s Proposed 70 Percent Top Marginal Income Tax Rate Would Deter Innovation,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 14, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/ocasio-cortezs-70-percent-tax-rate-deter-innovation/.

[26] Carolina Torres, “Taxes and Investment in Skills,” 43.

[27] Alastair Fitzpayne and Ethan Pollack, “Worker Training Tax Credit: Promoting Employer Investments in the Workforce,” The Aspen Institute, Aug. 16, 2018, https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/worker-training-tax-credit-update-august-2018/.

[28] The base level “would be determined by averaging the amounts spent in each of the three years prior to the current tax year.” See, Alastair Fitzpayne and Ethan Pollack, “Worker Training Tax Credit: Promoting Employer Investments in the Workforce.”

[29] Ibid.

[30] One justification for these limitations may be to prevent deductions for education pursued as a hobby or recreation, or education that may not be related to business activities. Lawmakers would need to consider this aspect as it relates to deductibility.

[31] Caleb Watney, “Reducing Entry Barriers In The Development And Application Of AI.”

[32] Senate Bill 275 116th Congress, “Skills Investment Act of 2019,” https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/275?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22S.275%22%5D%7D&s=3&r=1.

[33] Jose Trejos, “If Retained, R&D Tax Credit Should Be Reformed,” Tax Foundation, July 20, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/rd-tax-credit-reform/.

[34] Erica York, “Evaluating Education Tax Provisions.”

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Tax Treatment of Worker Training

by r Hampton | Mar 20, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – State Individual Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2019

Key Findings

-

Individual income taxes are a major source of state government revenue, accounting for 37 percent of state tax collections.

-

Forty-three states levy individual income taxes. Forty-one tax wage and salary income, while two states–New Hampshire and Tennessee–exclusively tax dividend and interest income. Seven states levy no income tax at all.

-

Of those states taxing wages, nine have single-rate tax structures, with one rate applying to all taxable income. Conversely, 32 states levy graduated-rate income taxes, with the number of brackets varying widely by state. Hawaii has 12 brackets, the most in the country.

-

States’ approaches to income taxes vary in other details as well. Some states double their single-bracket widths for married filers to avoid the “marriage penalty.” Some states index tax brackets, exemptions, and deductions for inflation; many others do not. Some states tie their standard deductions and personal exemptions to the federal tax code, while others set their own or offer none at all.

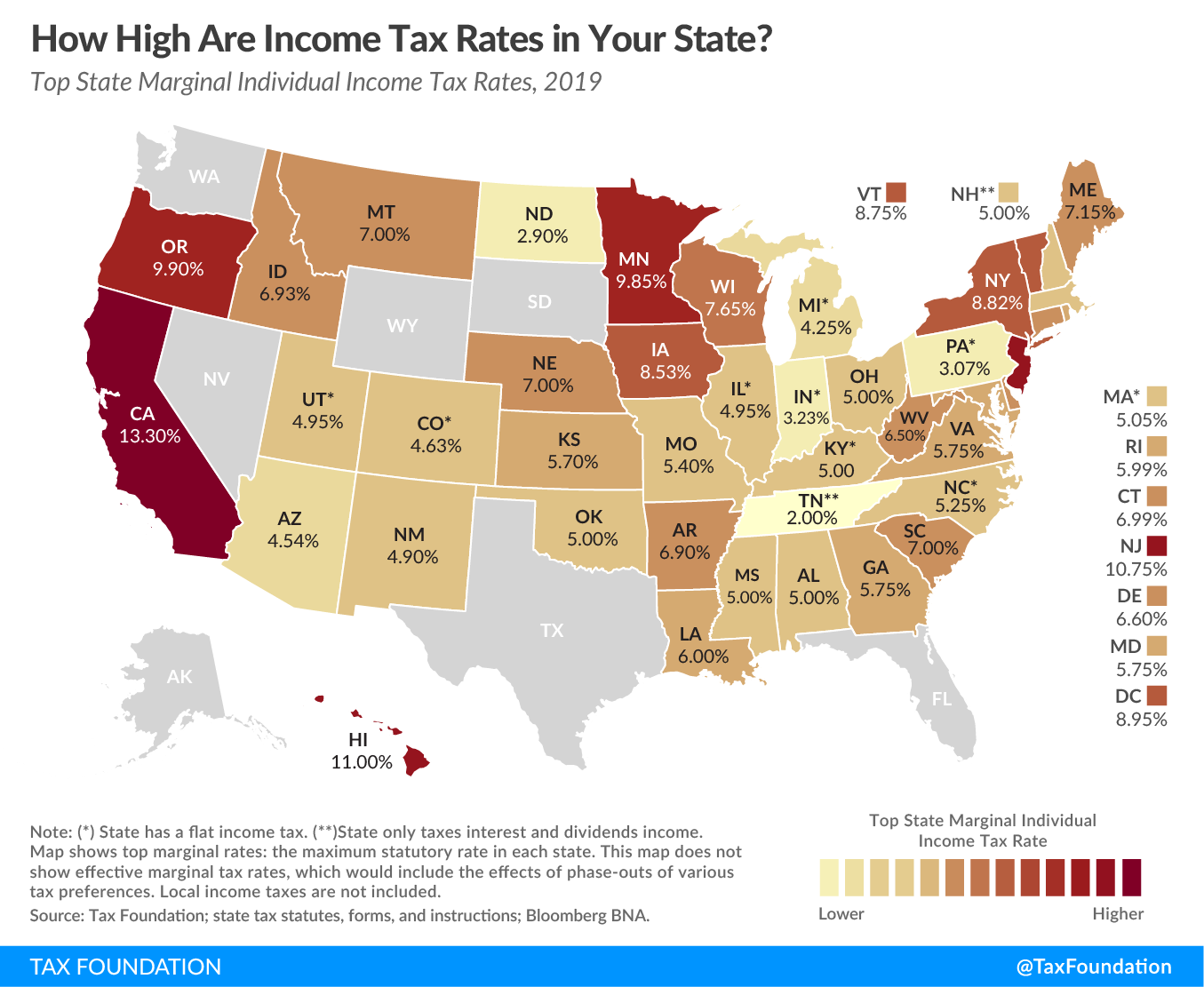

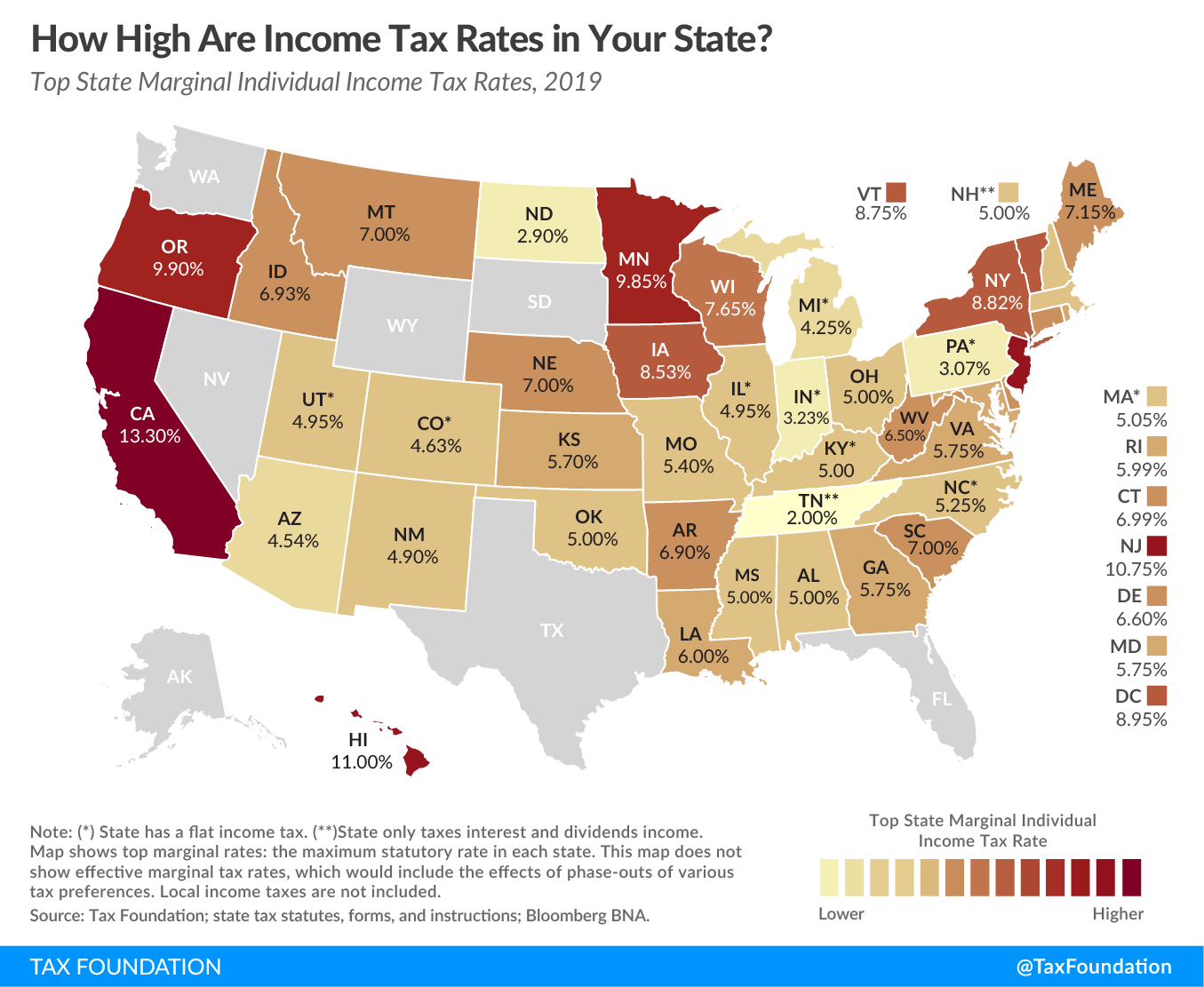

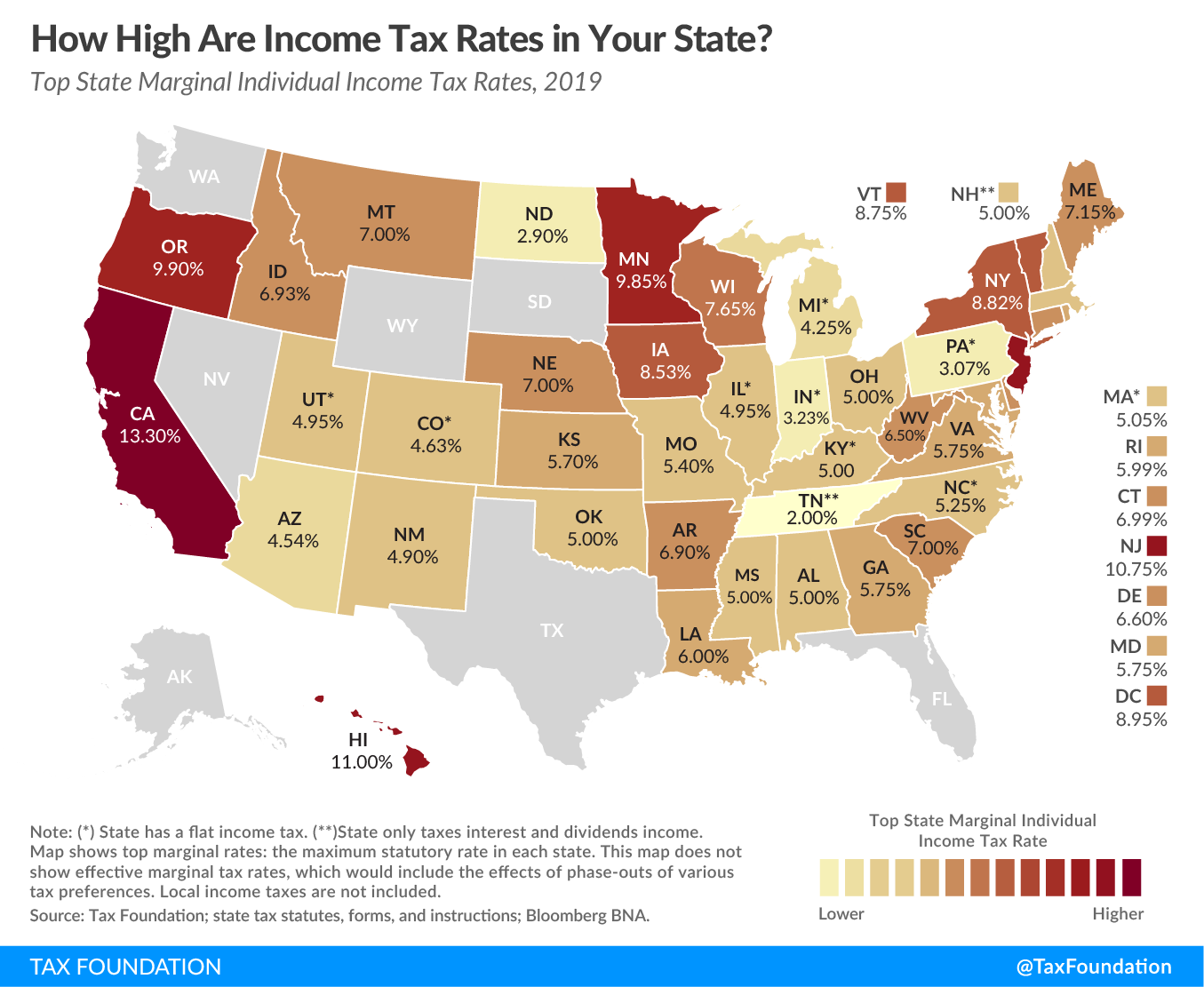

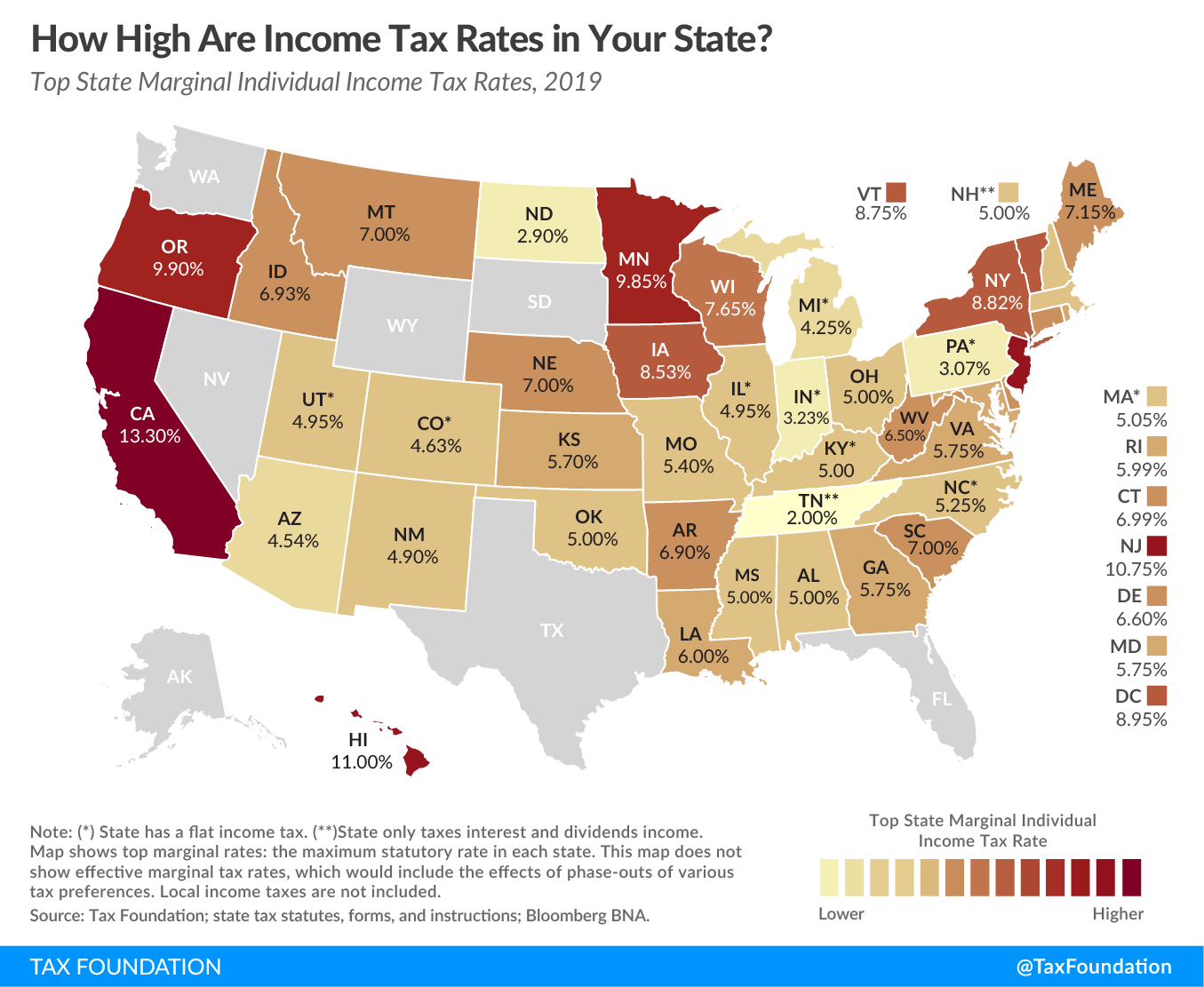

Individual income taxes are a major source of state government revenue, accounting for 37 percent of state tax collections.[1] Their prominence in public policy considerations is further enhanced by the fact that individuals are actively responsible for filing their income taxes, in contrast to the indirect payment of sales and excise taxes.

Forty-three states levy individual income taxes. Forty-one tax wage and salary income, while two states–New Hampshire and Tennessee–exclusively tax dividend and interest income. Seven states levy no income tax at all. Tennessee is currently phasing out its Hall Tax (income tax applied only to dividends and interest income) and is scheduled to repeal its income tax entirely for tax years beginning January 1, 2021.[2]

Of those states taxing wages, nine have single-rate tax structures, with one rate applying to all taxable income. Conversely, 32 states levy graduated-rate income taxes, with the number of brackets varying widely by state. Kansas, for example, imposes a three-bracket income tax system. At the other end of the spectrum, Hawaii has 12 brackets, and California has 10. Top marginal rates range from North Dakota’s 2.9 percent to California’s 13.3 percent.

In some states, a large number of brackets are clustered within a narrow income band; Georgia’s taxpayers reach the state’s sixth and highest bracket at $7,000 in annual income. In the District of Columbia, the top rate kicks in at $1 million, as it does in California (when the state’s “millionaire’s tax” surcharge is included). New York and New Jersey’s top rates kick in at even higher levels of marginal income: $1,077,550 and $5 million, respectively.

States’ approaches to income taxes vary in other details as well. Some states double their single-bracket widths for married filers to avoid the “marriage penalty.” Some states index tax brackets, exemptions, and deductions for inflation; many others do not. Some states tie their standard deductions and personal exemptions to the federal tax code, while others set their own or offer none at all. In the following table, we provide the most up-to-date data available on state individual income tax rates, brackets, standard deductions, and personal exemptions for both single and joint filers.

The 2017 federal tax reform law increased the standard deduction (set at $12,200 for single filers and $24,400 for joint filers in 2019), while suspending the personal exemption by reducing it to $0 through 2025. Because many states use the federal tax code as the starting point for their own standard deduction and personal exemption calculations, some states that are coupled to the federal tax code updated their conformity statutes in 2018 to either adopt federal changes or retain their previous deduction and exemption amounts.

Notable Individual Income Tax Changes in 2019

Several states changed key features of their individual income tax codes between 2018 and 2019. These changes include the following:

- As part of a broader tax reform package, Kentucky replaced its six-bracket graduated-rate income tax, which had a top rate of 6 percent, with a 5 percent single-rate tax.[3]

- New Jersey created a new top rate of 10.75 percent for marginal income $5 million and above.[4]

- In adopting legislation to conform to changes in the federal tax code, Vermont eliminated its top individual income tax bracket and reduced the remaining marginal rates by 0.2 percentage points across the board.[5]

- Iowa adopted comprehensive tax reform legislation with tax changes that phase in over time. For tax year 2019, income tax rates are reduced across the board, and in 2023, subject to revenue triggers, nine brackets will be consolidated into four, with the top rate reduced to 6.5 percent.[6]

- Idaho adopted conformity and tax reform legislation that included a 0.475 percentage point across-the-board income tax rate reduction.[7]

- Missouri eliminated one of its income tax brackets and reduced the top rate from 5.9 to 5.4 percent as part of a broader conformity and tax reform effort.[8]

- Utah reduced its single-rate individual income tax from 5 to 4.95 percent.[9]

- Arkansas is unique among states in that it has three entirely different rate schedules depending on a taxpayer’s total taxable income. In 2018, Arkansas adopted low-income tax relief legislation that reduced marginal rates in the lowest-income schedule, as well as the lowest rate in the next income schedule.[10]

- Georgia reduced its top marginal individual income tax rate from 6 to 5.75 percent as part of a conformity measure, but this provision is set to expire at the end of 2025 when income tax changes are scheduled to sunset at the federal level.[11]

- North Carolina’s flat income tax was reduced from 5.499 to 5.25 percent.[12]

Notes

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, “State & Local Government Finance,” Fiscal Year 2016, https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2016/econ/local/public-use-datasets.html.

[2] Tennessee Department of Revenue, “Hall Income Tax Notice,” May 2017. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/revenue/documents/notices/income/income17-09.pdf.

[3] Morgan Scarboro, “Kentucky Legislature Overrides Governor’s Veto to Pass Tax Reform Package,” Tax Foundation, April 16, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/kentucky-tax-reform-package/.

[4] Ben Strachman and Scott Drenkard, “Business and Individual Taxpayers See No Reprieve in New Jersey Tax Package,” Tax Foundation, July 3, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/individual-income-tax-corporate-tax-hike-new-jersey/.

[5] Jared Walczak, “Toward a State of Conformity: State Tax Codes a Year After Federal Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 28, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/state-conformity-one-year-after-tcja/.

[6] Jared Walczak, “What’s in the Iowa Tax Reform Package,” Tax Foundation, May 9, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/whats-iowa-tax-reform-package/.

[7] Katherine Loughead, “Five States Accomplish Meaningful Tax Reform in the Wake of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Foundation, July 23, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/five-states-accomplish-meaningful-tax-reform-wake-tax-cuts-jobs-act/.

[8] Jared Walczak, “Toward a State of Conformity: State Tax Codes a Year After Federal Tax Reform.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Nicole Kaeding, “Tax Cuts Signed in Arkansas,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 2, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-cuts-signed-arkansas/.

[11] Jared Walczak, “Tax Changes Taking Effect January 1, 2019,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 27, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-tax-changes-january-2019/.

[12] Ibid.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – State Individual Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2019

by r Hampton | Mar 19, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Tax Competition of a Different Flavor at the OECD

Last week the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) hosted a public consultation on several proposals to rearrange international tax rules. The policies up for discussion include three separate approaches to reallocate taxing rights among countries and two proposals to institute a minimum level of taxation for multinational corporations. In the context of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project Action 1, the OECD has categorized the separate proposals as Pillar 1 (rearranging of taxing rights) and Pillar 2 (minimum tax approach) policies.

The Pillar 1 proposals include a rearranging of taxing rights based on:

- Profits derived from user contributions in a market country

- Profits attributable to marketing intangibles investments

- Allocation of taxing rights using a formula including sales, assets, employees, and potentially users

The Pillar 2 proposals include stronger base erosion protections including:

- A global minimum tax approach like the U.S. Global Intangible Low Tax Income (GILTI)

- A tax on base eroding payments like the U.S. Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT)

The public consultation provided a forum for stakeholders to provide their views on these proposals. Respondents included tax professionals, business leaders, and civil society organizations. The Tax Foundation participated in the consultation and had previously submitted a written response to the OECD consultation.

Several key themes arose during the discussion including concerns over the potential complexity of implementing the proposals, a desire for evaluation of recent changes to international tax rules prior to adoption of new approaches, a warning to avoid creating double taxation scenarios, and a willingness to work toward a pragmatic solution.

Complexity Concerns

The potential complexity could arise from several standpoints. The reallocation of taxing rights would create new tax liabilities for businesses in jurisdictions where they currently do not pay tax for one reason or another. When those liabilities arise, businesses may face challenges in filing tax returns or understanding why a withholding tax applies in a particular jurisdiction.

Respondents noted that complexity could also come from new rules being layered on top of current international tax rules without reconciling differences between the two. Conflicts over the application of current transfer pricing rules (which guide the taxation of cross-border transactions within companies) could be exacerbated if the uncertainties of transfer pricing valuations are relied upon in calculating which country taxes what share of a business’s profits.

Current international tax rules and their intersection with double tax treaties are by no means simple. Any proposal to change international tax rights should take this complexity into account.

One respondent specifically identified ways that current rules create challenges for customs authorities and that shifting to a new set of rules could create challenges not only in tax administration, but also for customs and trade authorities.

There was also discussion of how the OECD might create safe harbors either for countries or for businesses to allow them alternatives for simpler compliance or administration of the new rules. Those simplifications could, potentially, provide businesses with more tax certainty than they currently have.

Several respondents also pointed out that the U.S. GILTI and BEAT policies have created significant compliance and tax burdens and may not be the best models for the OECD to follow. Concerns were raised that these policies may not fit well with current tax rules and could create very complex tax outcomes for some industries.

Evaluation Before Implementation

Several respondents noted that countries have only recently been implementing proposals resulting from the BEPS project. These include tougher transfer pricing regulations, patent box nexus rules, controlled foreign corporation rules, and country-by-country reporting. Respondents at the consultation noted that the effectiveness of these recently adopted policies should be evaluated prior to the OECD work on new policies to minimize base erosion.

This is an important issue for the OECD to consider. The current push for rearranging international tax rules has loosely defined objectives, and it is possible that the current policies on the books meet those objectives. However, it is still too early to measure the effectiveness of these policies on profit shifting.

Respondents including the Tax Foundation noted the importance of not only understanding the state of policy as it stands right now, but also the importance for the OECD to be measuring how various Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 policies could impact revenues and business activity.

Don’t Tax Us Twice

Another key theme from the consultation was the potential for double taxation of the same income under various scenarios. Multiple respondents focused on how Pillar 2 options could create likely scenarios for several layers of tax on the same income.

One respondent walked the audience through a scenario where a company with offices in four countries could face five different layers of tax due to the interaction of various BEPS and Pillar 2 policies. Multiple layers of tax on the same income create both administrative and economic burdens as the tax paid may not align with profits generated in one jurisdiction over another.

The OECD was encouraged to study the potential for double taxation and to allow for dispute prevention between taxing jurisdictions so that companies could avoid having income taxed by more than one tax authority at a time.

Pragmatic Approaches

Some respondents provided comments admitting that they were willing to be pragmatic in working toward a solution. However, as one respondent noted, a pragmatic solution without principle might result in an unstable agreement. The OECD should therefore focus on adopting new proposals that align with shared principles and an agreed-upon rationale.

The pragmatism was also evidenced in the suggestion of a formulaic approach to rearranging taxing rights. A formula approach based on some measurable metric like sales in a jurisdiction could simplify both tax compliance and tax administration. Unfortunately, at this stage there is not enough detail in either the OECD approaches or the suggested formulas to determine the effects of any of the approaches.

Conclusion

The public consultation resulted in general agreement that something needs to change in the international tax rules, but also that there could be significant challenges to implementing that change. As Tax Foundation reminded the audience during the consultation, it is important to recognize that businesses are central to tax collection systems and the importance of having a discussion that is informed by the facts.

The OECD will continue to review the comments that have been received and is expected to publish a work plan in early summer. The OECD has a goal of reaching an agreement on a new policy in 2020. Tax Foundation will continue to monitor the OECD’s work on these proposals and will follow up with further analysis.

Daniel Bunn discusses the need to look at how each policy impacts the cost of capital and incentives to invest as well as overall tax complexity. Click the image above to watch.

Scott Hodge emphasizes that corporate income taxes impact workers and consumers as well as businesses. Click the image above to watch.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Tax Competition of a Different Flavor at the OECD

TAXTIMEKC

TAXTIMEKC