by r Hampton | Mar 19, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Increasing Individual Income Tax Rates Would Impact a Majority of U.S. Businesses

Most U.S. businesses are not subject to the corporate income tax. Instead, most U.S. businesses are pass-through businesses, such as partnerships, S corporations, LLCs, and sole proprietorships. These businesses “pass” their income “through” to their owners, which is reported on the owners’ individual income tax returns. Overall, pass-through businesses account for more net income than corporations, meaning an increase in individual income tax rates will impact a majority of U.S. businesses.

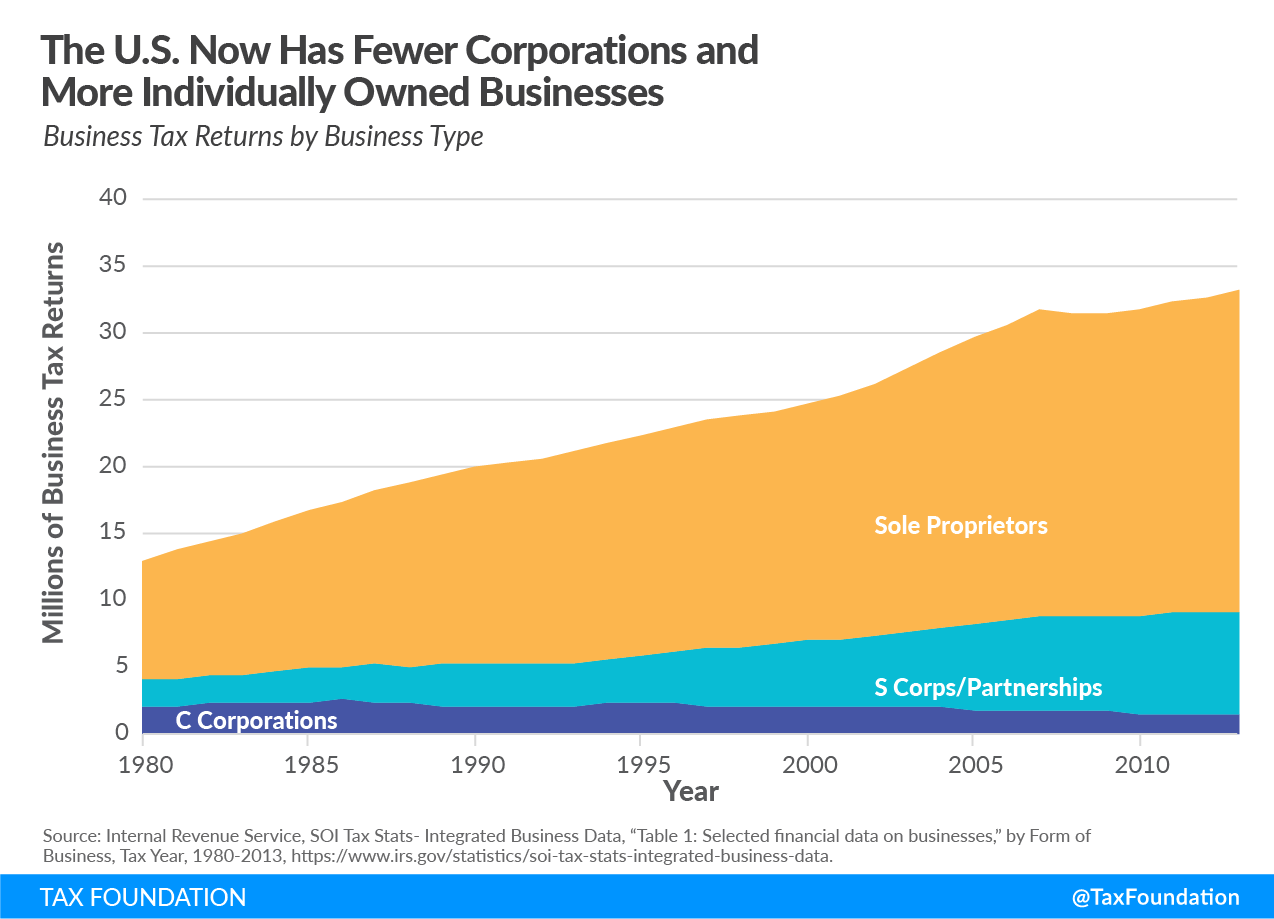

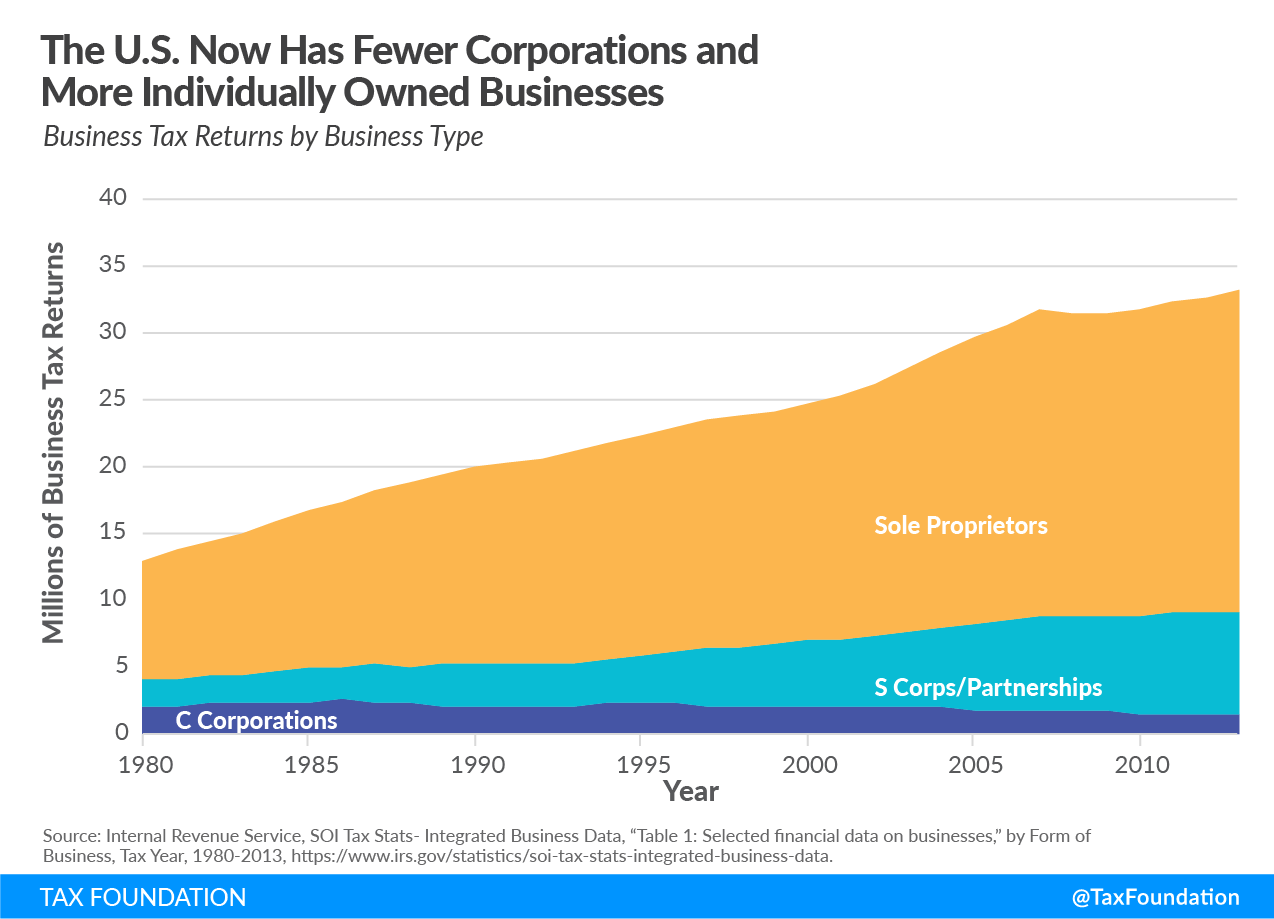

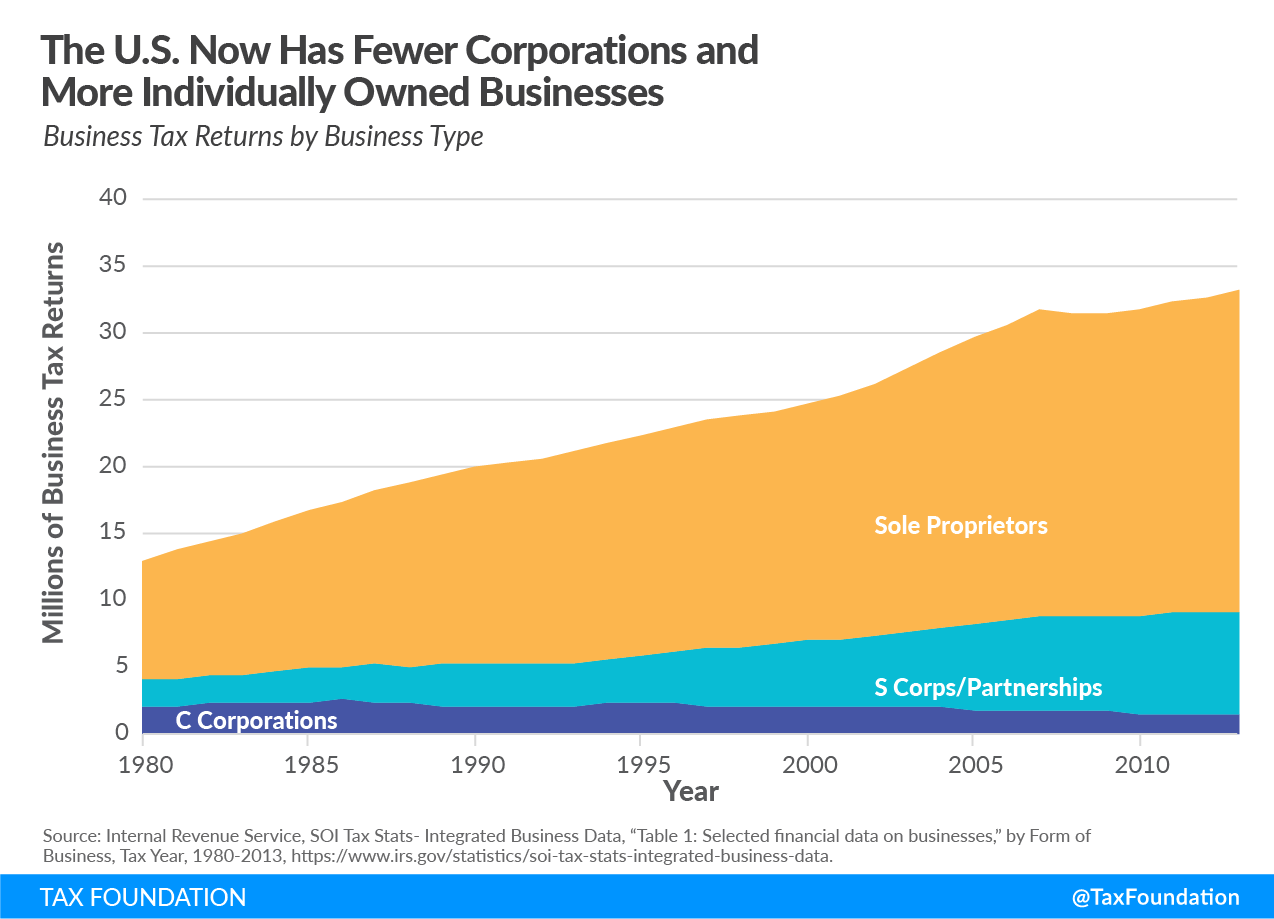

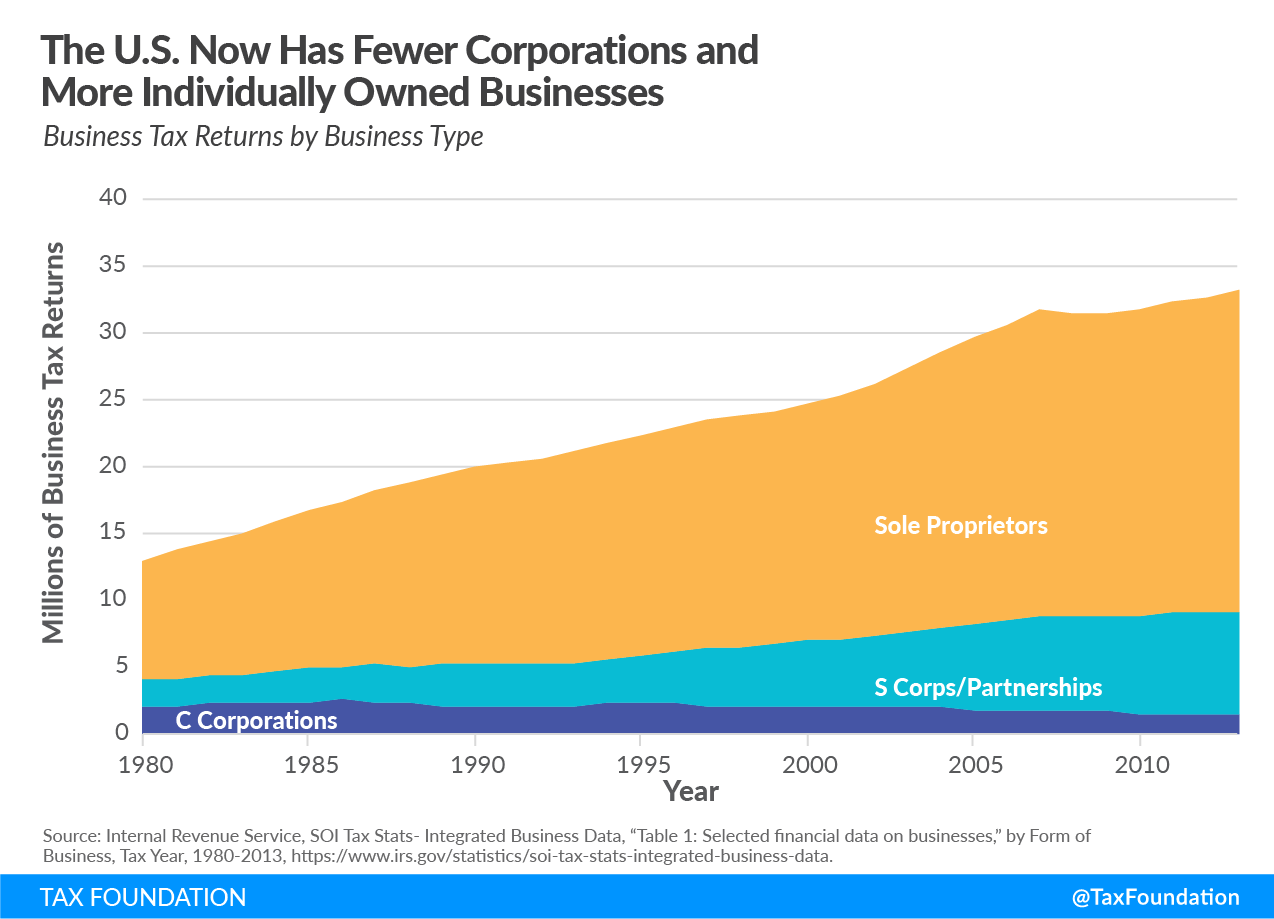

Pass-through businesses represent the ideal tax treatment of a business form. Unlike C corporations, pass-throughs are only subject to one layer of tax, the proper tax structure. Over time, the size of the pass-through sector has increased. Since the 1980s, the number of corporations has decreased from a high of almost 2.6 million in 1986 to about 1.6 million in 2013. On the other hand, the number of sole proprietorships has increased from about 9 million in 1980 to more than 24 million in 2013. The number of S corporations and partnerships increased from 2 million to almost 8 million over the same period.

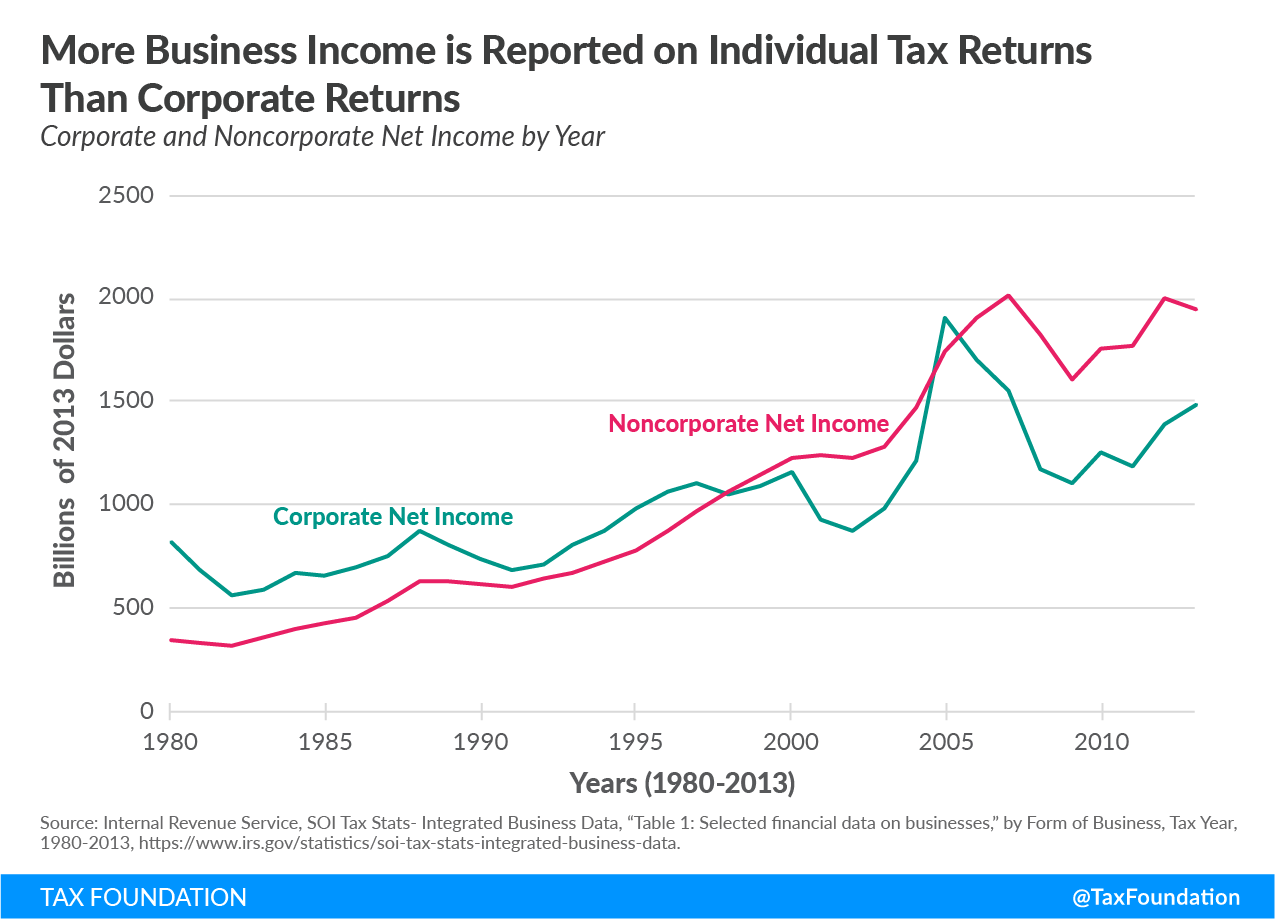

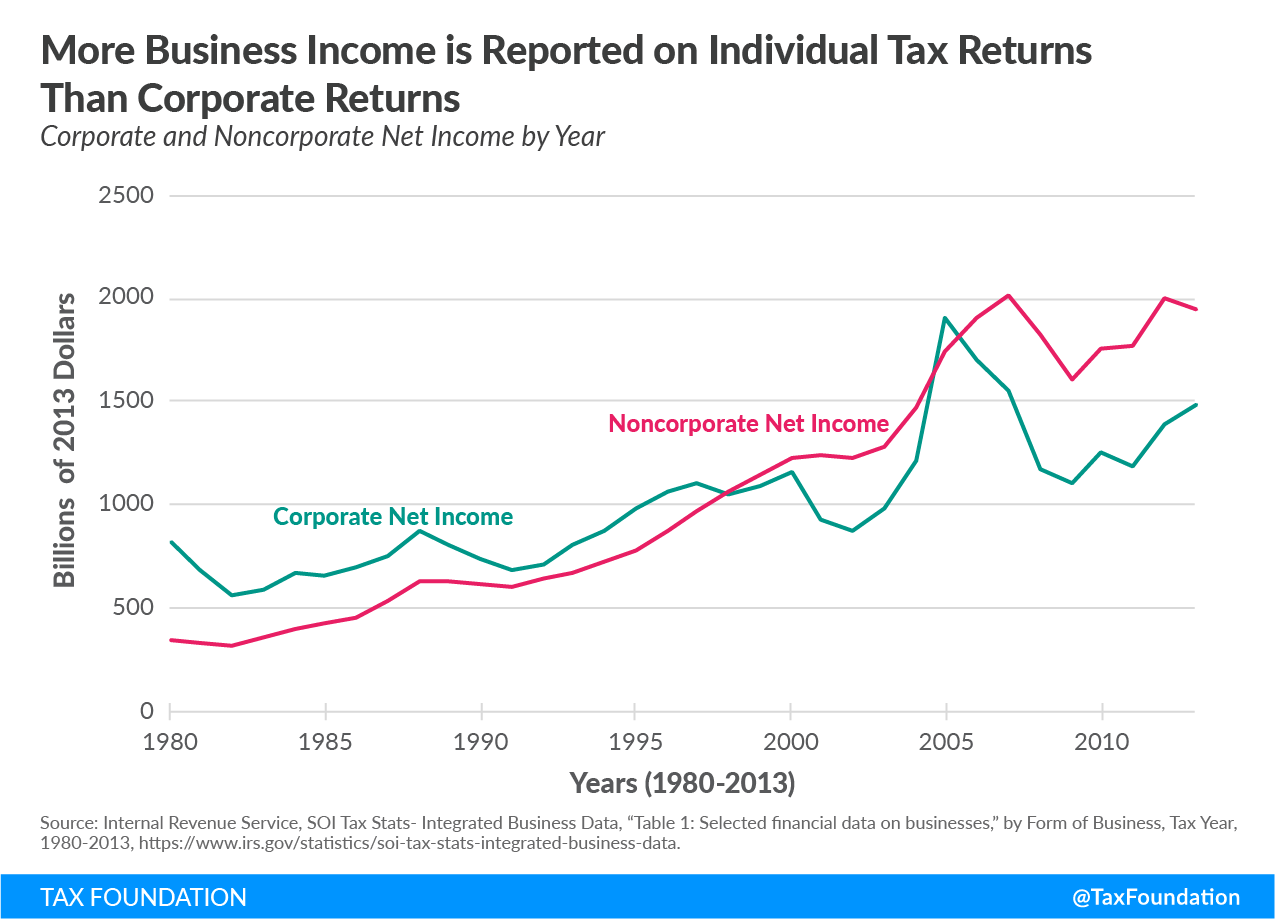

This growth in pass-through businesses relative to C corporations means more net business income is reported on individual income tax returns than on traditional C corporation returns. Aside from a brief period in the mid-2000s when corporate income spiked at the top of a business cycle, noncorporate business income has consistently exceeded corporate income since 1997.

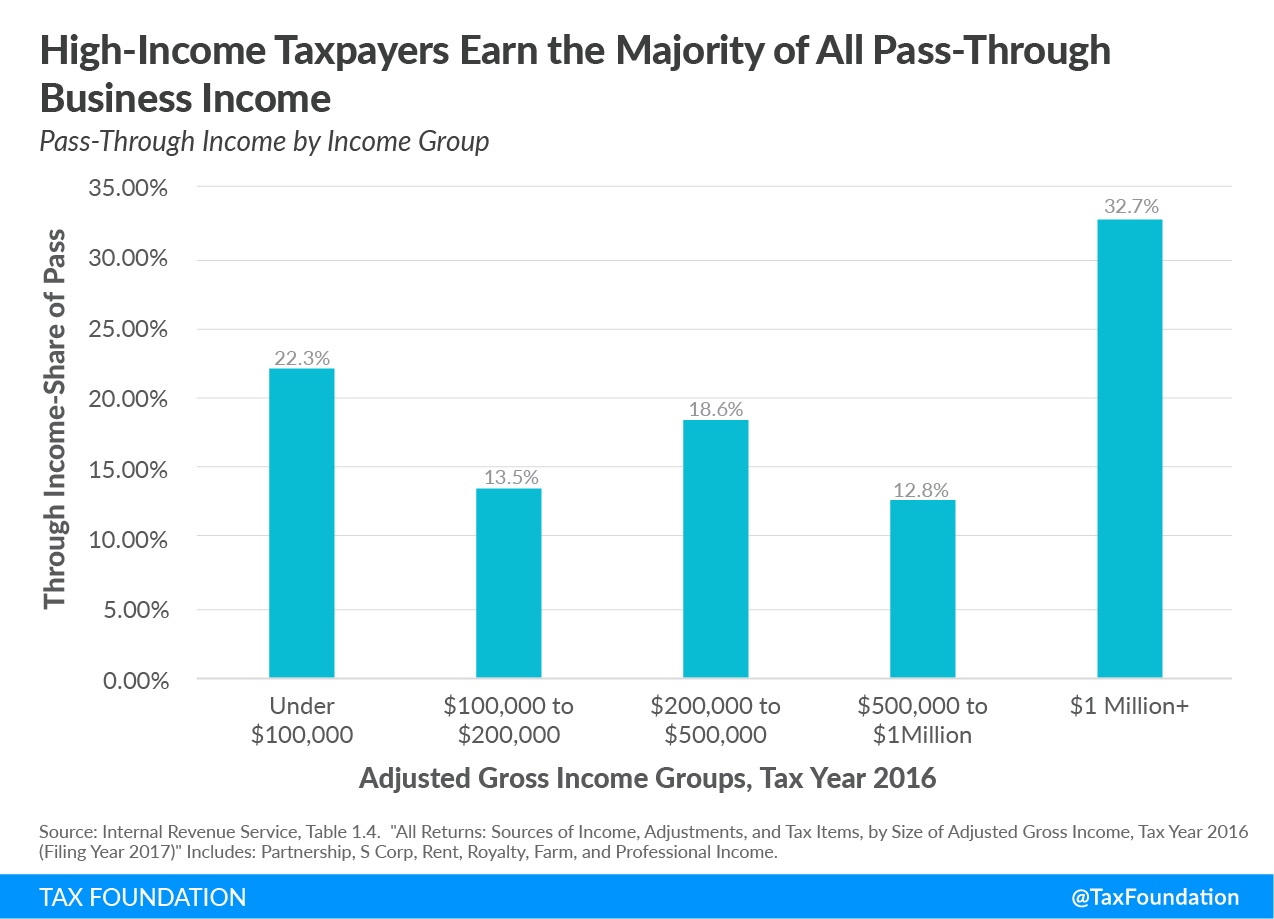

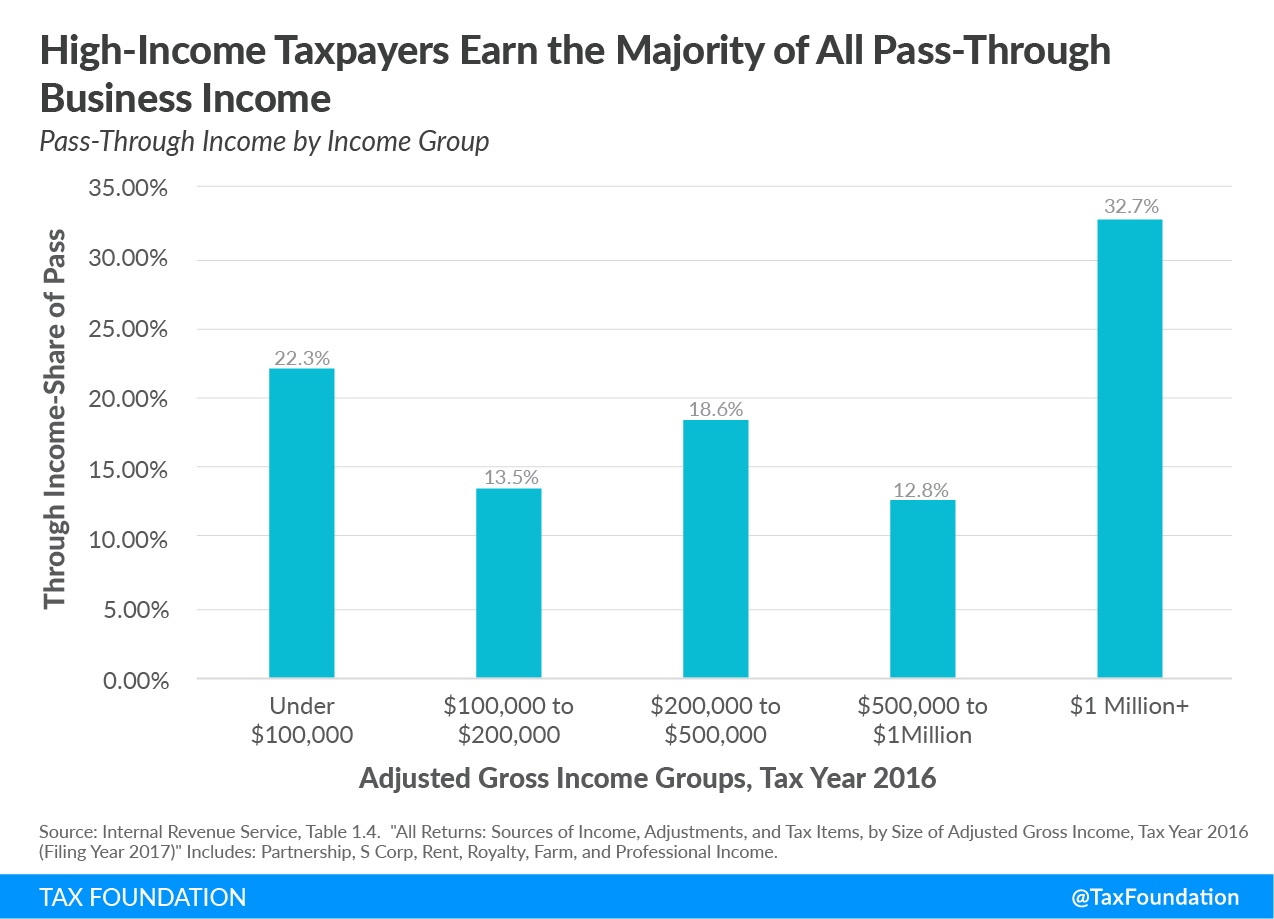

Pass-through business income is concentrated among high-income taxpayers. In 2016, more than 45 percent of pass-through business income was earned by taxpayers making more than $500,000 annually. Specifically, taxpayers making more than $1 million accounted for nearly a third of pass-through income.

This data shows that a large amount of business income is hit by the high marginal individual income tax rates. As a pass-through business earns more income, higher marginal rates gradually take more out of each dollar. Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, individual income tax rates take 37 cents of every dollar of income earned in the top tax bracket, though this rate is reduced for some qualifying pass-through businesses by the TCJA’s Section 199A provisions which allow qualifying taxpayers to deduct 20 percent of their pass-through business income from federal income tax.

Progressive marginal rates can discourage pass-through business owners from conducting business activities that would increase their income—such as investing in new capital, hiring workers, and producing goods for consumers.

When we think about who is subject to the individual income tax, this data shows us that a significant burden is borne by businesses. Changes to the individual income tax, especially to top marginal rates, can affect a business’s incentives to invest, hire, and produce.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Increasing Individual Income Tax Rates Would Impact a Majority of U.S. Businesses

by r Hampton | Mar 18, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Maine’s Water Extraction Tax Proposal Is Poor Tax Policy

Lawmakers in Maine’s 129th legislature have proposed a bill (HP 797) to impose an excise tax of 12 cents per gallon on water extraction performed by each bottled water operator that extracted more than 1 million gallons of groundwater or surface water in the previous calendar year. This plan purports to stimulate the economy of rural Maine, and credits new revenue to the Water Trust Fund.

Specifically, 65 percent of the revenue would be earmarked to develop high-speed broadband infrastructure. The remaining 35 percent would be directed to provide tuition grants for postsecondary education for up to two years.

The proposal for a water extraction tax, which is not a new idea in Maine, is poor tax policy because it is nonneutral and unstable, and it would open the way to taxing renewable resources.

Three previous bills in Maine’s legislature attempted to impose similar excise taxes at various rates and for various purposes; all were rejected. In 2009, HP 191 was proposed to tax water at one cent per gallon; in 2015, HP 127 would also have imposed a water extraction tax of one cent per gallon; and in 2017, HP 356 aimed to tax water at a rate of one cent per 25 gallons extracted. Revenue allocation varied for each bill. The proposals included programs to finance watershed and water quality protection, lake water quality monitoring, water testing, tax relief for local residents and municipalities, and programs for K-12 education.

A tax on water extraction would mark the first time the Maine legislature taxed a renewable resource, opening a new frontier of tax policy without a clear justification. That is not the only reason why taxing water extraction is questionable public policy. Although it easy to administer such a tax on a very small base of producers, it is a highly discriminatory tax that targets a small number of companies in a single industry without the normal justifications for an excise tax. This violates the principle of tax neutrality because the tax is so narrowly targeted upon certain companies. Furthermore, taxing such a small base of companies violates the principle of tax stability by attaching government programs to a volatile and uncertain revenue source depending on the operations of a small handful of businesses.

Poland Spring is the only company in Maine that would be subjected to such taxation. As a landowner, however, the company currently owns the rights to access water according to Maine law. The public expenditures planned for the water tax are not directly related to Poland Springs or even to water usage generally, putting this tax in contradiction with the benefit principle of tax policy.

The company currently has three bottling plants operating in Maine, where they have hundreds of jobs. Ironically, the stated purpose of the bill is to secure the economic future of rural Maine. However, the bill attempts to do so in a way that could negatively impact rural jobs and reduce the economic competitiveness of Maine’s rural communities.

The arguments in favor of traditional severance and extraction taxes are not justified in the case of water extraction because water is a renewable resource.

Severance and extraction taxes are often imposed on the extraction of nonrenewable natural resources, such as crude oil and natural gas, on the grounds that it encourages resource conservation. Sometimes the tax is imposed to “price-in” the externalities caused by extracting and using such resources, and the tax revenue gained can be used to mitigate the effects of those externalities. Furthermore, revenue generated from a severance tax might be used to address intergenerational inequity given that resources, once depleted, are not accessible for future generations. However, these issues are not relevant with regards to drinking water extraction because water is a renewable resource that is not being depleted.

In addition, taxing one form of water usage creates a nonneutral tax code with respect to water-related economic activity. There is no tax imposed on other types of water usage such as agricultural irrigation, power production, mining, and golf course irrigation. In fact, such water usage is sometimes subsidized by governmental utility authorities as a matter of public policy so that the water price can be kept artificially low. On the other hand, bottled water companies bear the full cost of their bottling infrastructure and transportation.

If rural broadband infrastructure and post-secondary education are state priorities, they should be funded by a stable and neutral revenue source. The logic behind traditional extraction taxes does not apply to the bottled water industry. Furthermore, the funding for efficient infrastructure and education should aim to meet the benefit principle of taxation. That is, people should pay taxes based on the benefits they receive. Taxing the extraction of water does not make sense as an excise tax and does not make sense as a mechanism to finance rural broadband and public education.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Maine’s Water Extraction Tax Proposal Is Poor Tax Policy

by r Hampton | Mar 14, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Senators Introduce Legislation to Fix the Retail Glitch

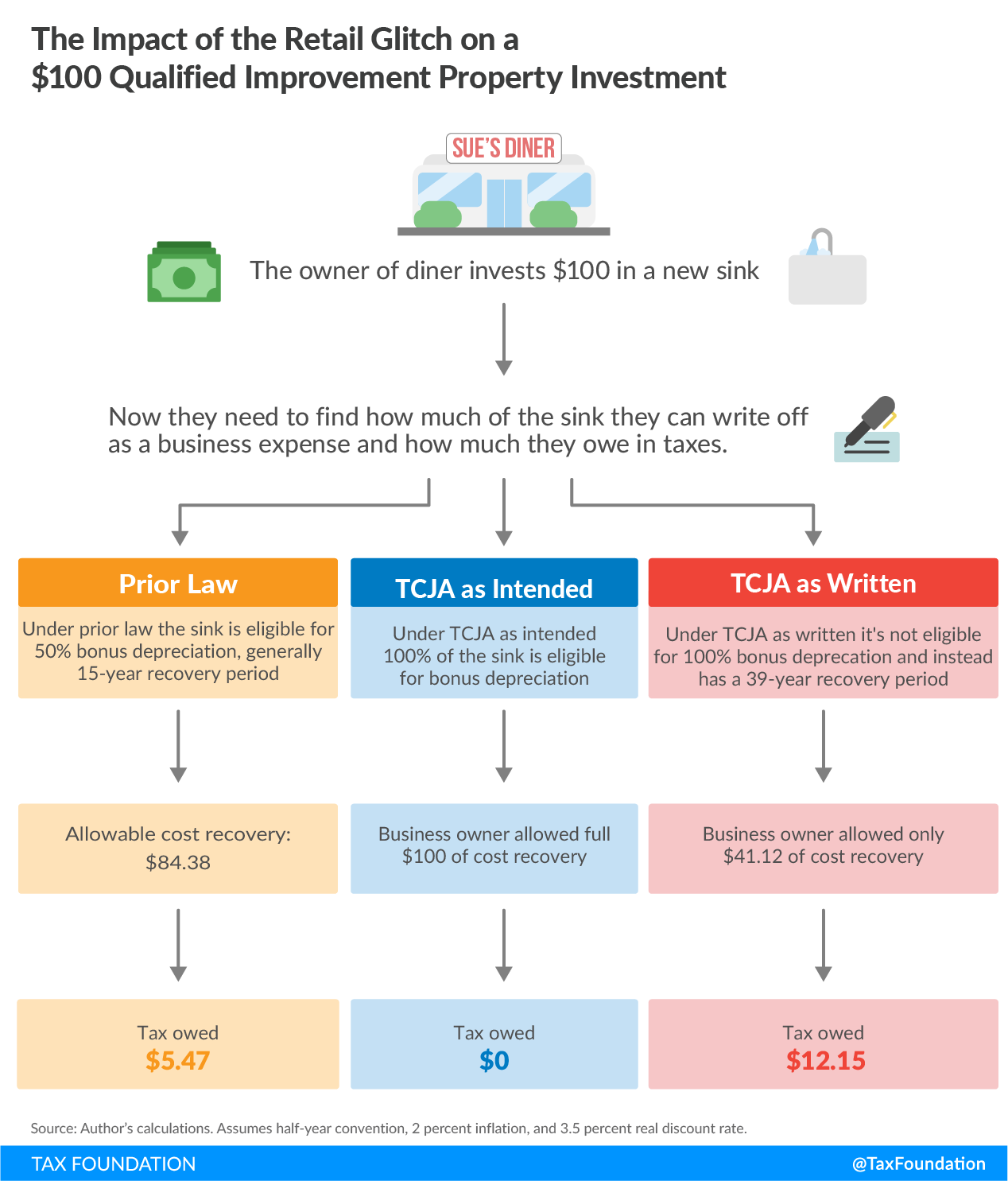

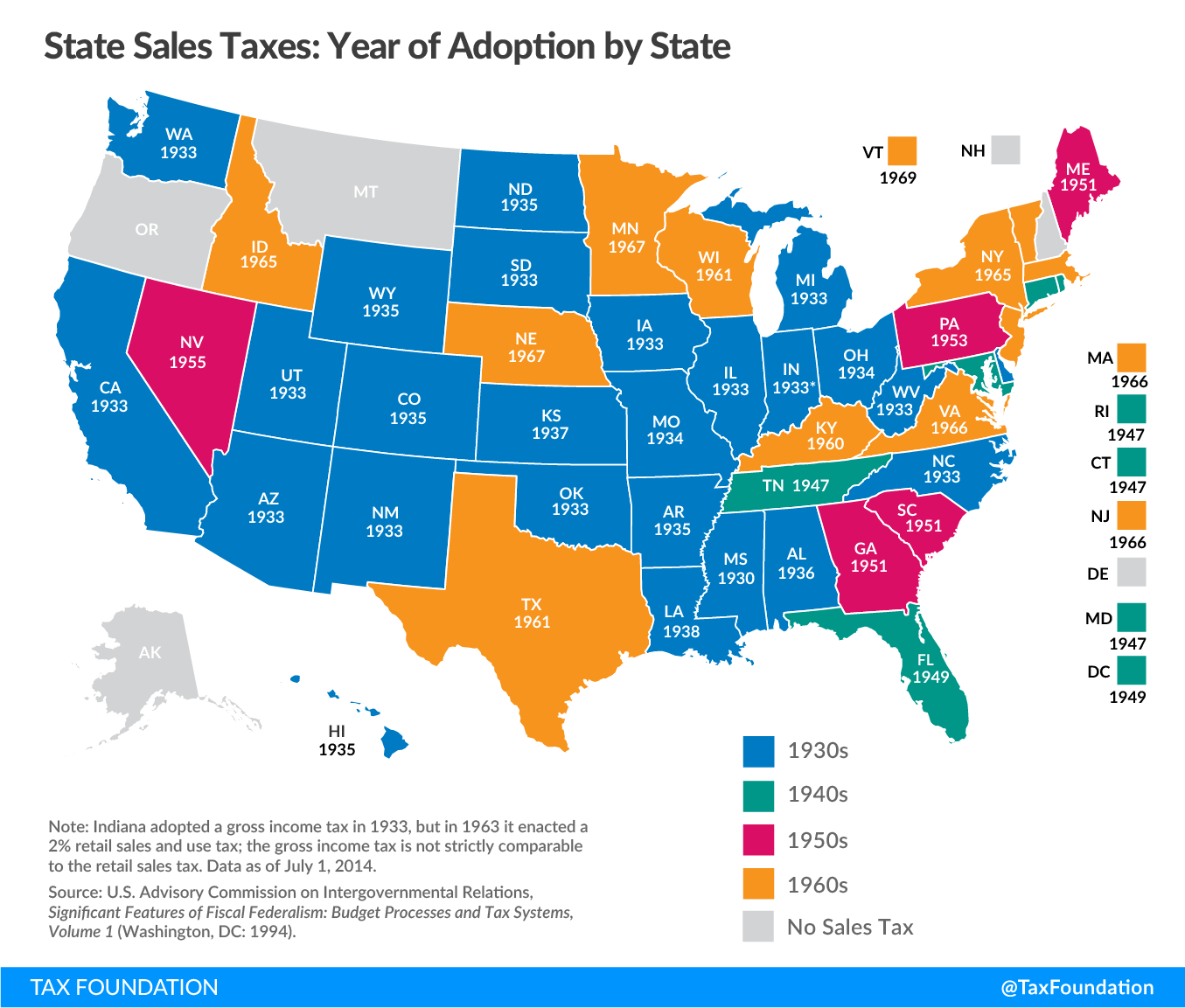

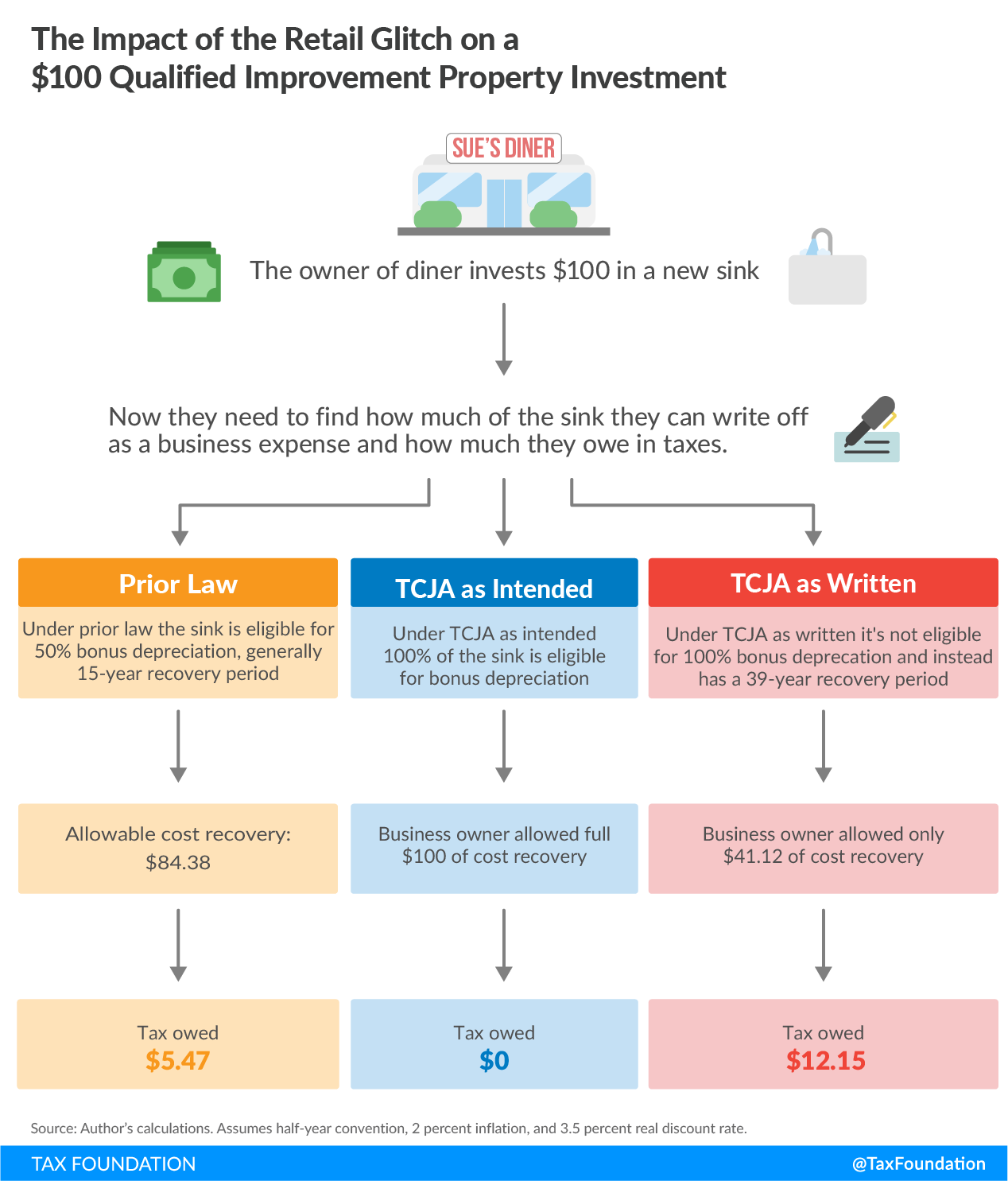

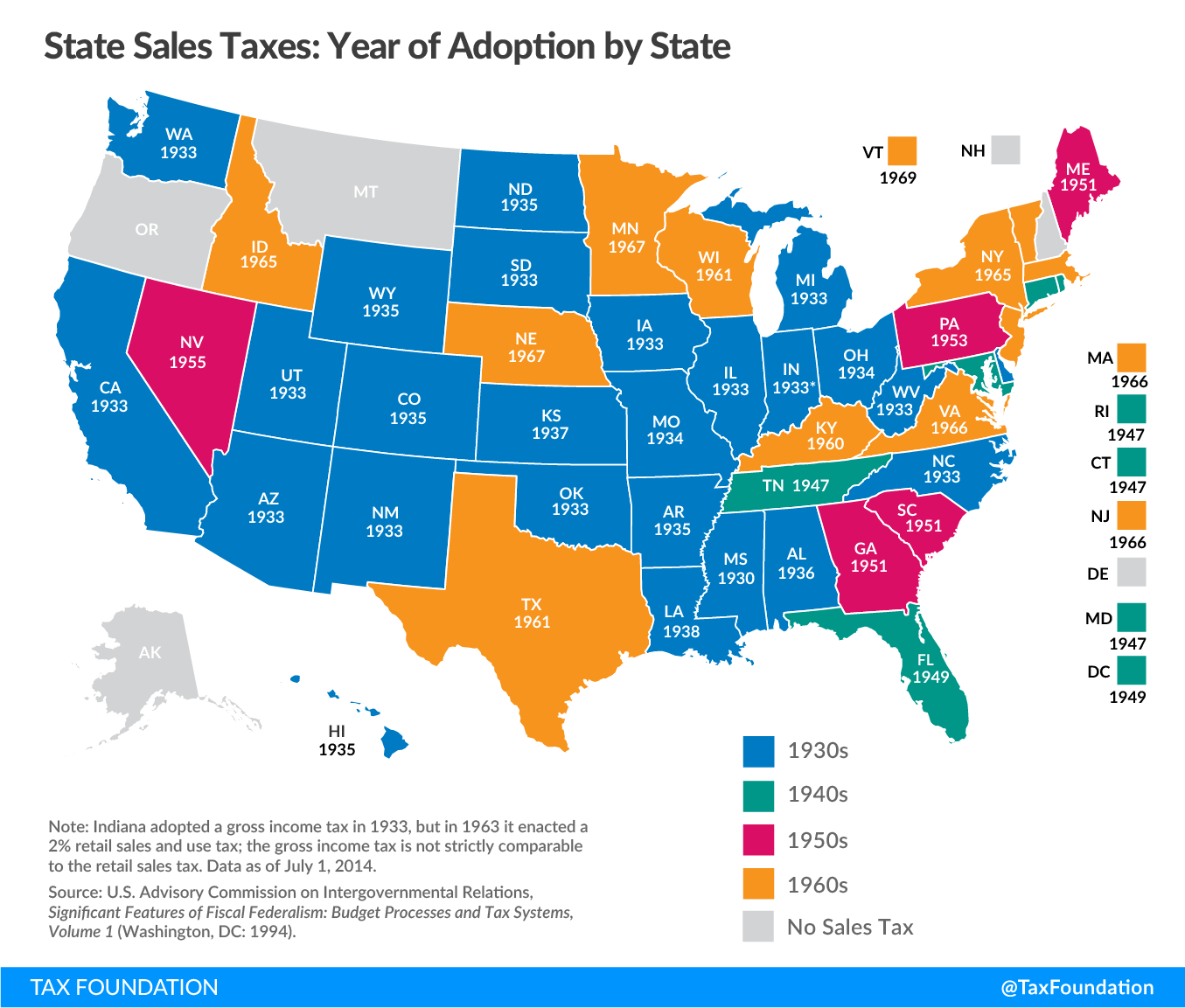

Today, Senators Pat Toomey (R-PA) and Doug Jones (D-AL) introduced a bill that would fix the “retail glitch.” The legislation addresses a clerical error in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) that prevents investments in qualified improvement property (QIP) from qualifying for bonus depreciation. This error significantly increased the after-tax cost of making QIP investments, and reportedly caused businesses to delay, and even turn down, investment opportunities that they otherwise would have pursued.

QIP investments include improvements to the inside of commercial buildings: projects such as new flooring, lighting fixtures, sprinkler systems, or other types of remodeling and interior improvements. The TCJA intended to consolidate the various categories of QIP that existed under old law into a new category with a 15-year cost recovery period. This would also have allowed QIP investments to be eligible for the 100 percent bonus depreciation provision created under the new law.

However, as written, the TCJA mistakenly excluded QIP from 100 percent bonus depreciation by leaving the cost recovery period unassigned, which results in a greater tax burden than under previous law. The infographic below shows how costly this mistake is.

Senators Toomey and Jones’ new bill would assign QIP a 15-year cost recovery period (and a 20-year alternative depreciation schedule cost recovery period), making these investments eligible for bonus depreciation. Importantly, the changes in this bill would take effect as if they were included in the original TCJA. And because the TCJA was scored as though QIP were eligible for the new provision, this fix does not increase the original cost of the new tax law.

Fixing the retail glitch would mean businesses no longer face more restrictive cost recovery treatment for investments in qualified improvement property than before tax reform.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Senators Introduce Legislation to Fix the Retail Glitch

by r Hampton | Mar 14, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Is Increasing the Capital Gains Tax Rate the Right Way to Generate Revenue?

In February, billionaires Warren Buffett and Bill Gates suggested increasing taxes on the wealthy to pay for policies that would help people without market skills keep pace in an increasingly specialized economy. Both have proposed increasing tax rates for capital gains as one potential way to generate revenue for this purpose.

Long-term capital gains, or appreciation on assets held for more than one year, are taxed at a lower rate than ordinary income when realized. For instance, the top individual income tax rate for individuals making more than $510,300 in 2019 is 37 percent, while the highest rate at which capital gains are taxed is 23.8 percent. This 23.8 percent top rate comes from the 20 percent rate for individuals with long-term capital gains over $434,550, as well as the 3.8 percent net investment income tax for individuals with modified adjusted gross income over $200,000.

One thing to recognize is that this reduced rate partially compensates taxpayers for double taxation. By the time taxpayers invest their income, that income has already been taxed by both the payroll and personal income taxes. The capital gains tax then places an additional layer of taxation on any returns in the investment purchased with after-tax income when taxpayers realize, or sell, their asset with a capital gain.

You shouldn’t look at this double taxation in isolation, because taxpayers who invest in capital gains get the benefit of deferral, making capital gains relatively more attractive from a tax standpoint compared to other investments. As my colleague Kyle Pomerleau points out:

The effective capital gains tax rate is already relatively low compared to the effective tax rate on other sources of capital income such as dividends and interest. This is mainly because individuals can delay realizing their capital gains, which reduces the present value of the tax burden.

This means the double taxation placed on capital gains isn’t mitigated just by the reduced rate, but also by the taxpayer’s ability to choose when they want to pay taxes on the capital gain. Taxpayers would still have this ability to time their capital gains realizations even if the reduced rate were increased.

Eliminating the reduced rate on capital gains would raise revenue, but it would also increase the cost of capital and the marginal tax rate on savings and investment—meaning that this might not be the best trade-off for policymakers.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Is Increasing the Capital Gains Tax Rate the Right Way to Generate Revenue?

by r Hampton | Mar 14, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – What’s up with Being GILTI?

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act made significant changes to the way U.S. multinationals’ foreign profits are taxed. GILTI, or “Global Intangible Low Tax Income,” was introduced as an outbound anti-base erosion provision. This new definition of income is meant to discourage companies from using intellectual property to shift profits out of the United States. However, GILTI in practice does not work the way in which many expected. Due to interactions with existing law, companies can face U.S. tax on GILTI even if their foreign effective tax rate is in excess of the advertised 13.125 percent. Ideally, this is something lawmakers should revisit. However, some argue that the Treasury Department should try to address this.

Structure and Purpose of GILTI

GILTI is a newly-defined category of foreign income added to corporate taxable income each year. In effect, it is a tax on earnings that exceed a 10 percent return on a company’s invested foreign assets. GILTI is subject to a worldwide minimum tax of between 10.5 and 13.125 percent on an annual basis. GILTI is supposed to reduce the incentive to shift corporate profits out of the United States by using intellectual property (IP).

The primary purpose of GILTI is to reduce the incentive for U.S.-based multinational corporations to shift profits out of the United States into low- or zero-tax jurisdictions. This is done by placing a floor on the average foreign tax rate paid by U.S. multinationals of between 10.5 percent and 13.125 percent. The incentive to shift profits from one jurisdiction to another is the function of the difference between the countries’ statutory tax rates. That difference is the tax savings a company receives per dollar shifted. Companies subject to GILTI would compare a 21 percent domestic rate with a 10.5 to 13.125 percent rate rather than a zero rate.

The 10 percent qualified business asset investment (QBAI) exemption in GILTI attempts to target the provision at assets that return above-normal returns, which is a proxy for the returns to intellectual property. This approach targets income that is more mobile. In addition, it exempts the returns to real investment, which should avoid distorting foreign investment decisions of U.S. multinational corporations. Under GILTI, the rate on foreign profits is now at or below most tax rates in the developed world. This limits the incentive for U.S. multinationals to move their headquarters out of the U.S.

Does GILTI Really Work as Intended?

In principle, GILTI is attempting to balance both base erosion and competitiveness concerns. However, it doesn’t seem like the law operates precisely as Congress intended.

One area which has garnered significant attention recently is GILTI’s treatment of companies with high-taxed foreign profits. For example, The Wall Street Journal highlighted a railroad transportation company that operates in the United States and Mexico. Although Mexico is a relatively high-tax country—it has a corporate income tax rate of 30 percent—this company was still subject to tax liability on its GILTI. Given that GILTI is meant to only apply to companies with tax liabilities under 13.125, this is a surprise.

The reason this company ends up facing tax liability is that GILTI was constructed using previous law’s foreign tax credit infrastructure. Under current law, foreign tax credits face a limitation. The limitation is that the credit is based on a formula, which cannot exceed your U.S. tax liability multiplied by the share of foreign profits divided by your worldwide profits. The purpose of this limitation is to prevent companies from using the foreign tax credit to offset domestic taxes.

Rules that are part of the foreign tax credit limitation also require companies to allocate certain domestic expenses to foreign income. This requirement to allocate domestic interest expense against foreign income has the effect of altering the fraction that limits the foreign tax credit. For example, a company, before the interest expense allocation, may earn half of its profits outside of the United States. This means the foreign tax credit would be limited to half of the U.S. tax liability. However, expense allocation may shift expenses out of the U.S. and into a foreign jurisdiction. As a result, foreign profits may fall to, say, 25 percent of overall profits. The foreign tax credit would then be limited to one quarter of U.S. tax liability—a far smaller foreign tax credit.

Under GILTI, the reduced foreign tax credit means that companies are not getting full credit for the taxes they pay already to foreign jurisdictions. Companies with foreign effective tax rates in excess of 20 percent could end up with additional U.S. tax liability on foreign profits, even though it exceeds the minimum GILTI rate of 13.125 percent.

What’s Next?

It does look as though lawmakers made a mistake in constructing GILTI. Expense allocation in the foreign tax credit was consistent with the previous worldwide tax system. However, it makes less sense in the context of a territorial tax system, which lawmakers clearly intended to move toward.

Ideally, lawmakers would work on legislation to revisit GILTI to make sure that it operates as originally intended: as a 10.5 to 13.125 percent minimum tax on foreign profits. However, there is little interest by lawmakers to do the heavy lifting in the short run. Alternatively, some companies argue that the Treasury Department could address this issue through further regulatory action. Treasury already released proposed rules that mitigated some of the effect of expense allocation in the foreign tax credit regarding GILTI. Other changes, such as looking at Subpart F’s high tax exemption, may also be discussed.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – What’s up with Being GILTI?

by r Hampton | Mar 13, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Utah Proposal to Modernize State Sales Should Avoid Layering Taxes on Business Inputs

Lawmakers in Utah considered and temporarily tabled a plan to expand the state’s sales tax to bring the Utah tax code in line with a 21st-century economy. The Tax Equalization and Reduction Act (HB 441 S1), proposed by Representative Tim Quinn (R), would expand the sales tax base to include nearly all goods and services. The new revenue would pay for reduced tax rates for both sales and income taxes.

However, the sales tax expansion also captures a large swath of business inputs. This creates a harmful effect known as “tax pyramiding” whereby economically distortive taxes stack up through the stages of business production, causing retail consumers to pay taxes upon taxes when they make a retail purchase.

The legislature does not intend to act on this proposal before wrapping up its session on March 14, leaving the opportunity to adjust the Tax Equalization and Reduction Act for a future session.

The Tax Equalization and Reduction Act

Major provisions from Representative Quinn’s proposal include that it:

- Broadens the state sales tax base to include all services except tuition, rent, and most medical services

- Repeals certain sales tax exemptions

- Imposes a 1% tax on medical insurance premiums written in the state

- Creates a real-estate transfer tax

- Reduces the state’s sales tax rate from 4.7% to 3.1%

- Reduces local options sales tax rates

- Reduces the state’s income tax rate from 4.95% to 4.75%

- Creates a refundable earned-income tax credit

It’s important to note that the sales tax would be levied on the services of a wide number of industries for which a significant portion of their sales are business-to-business transactions. These industries are referenced in lines 4331-4383 of the bill, including engineering, electrical and HVAC work, manufacturing, trucking, transportation, and banking.

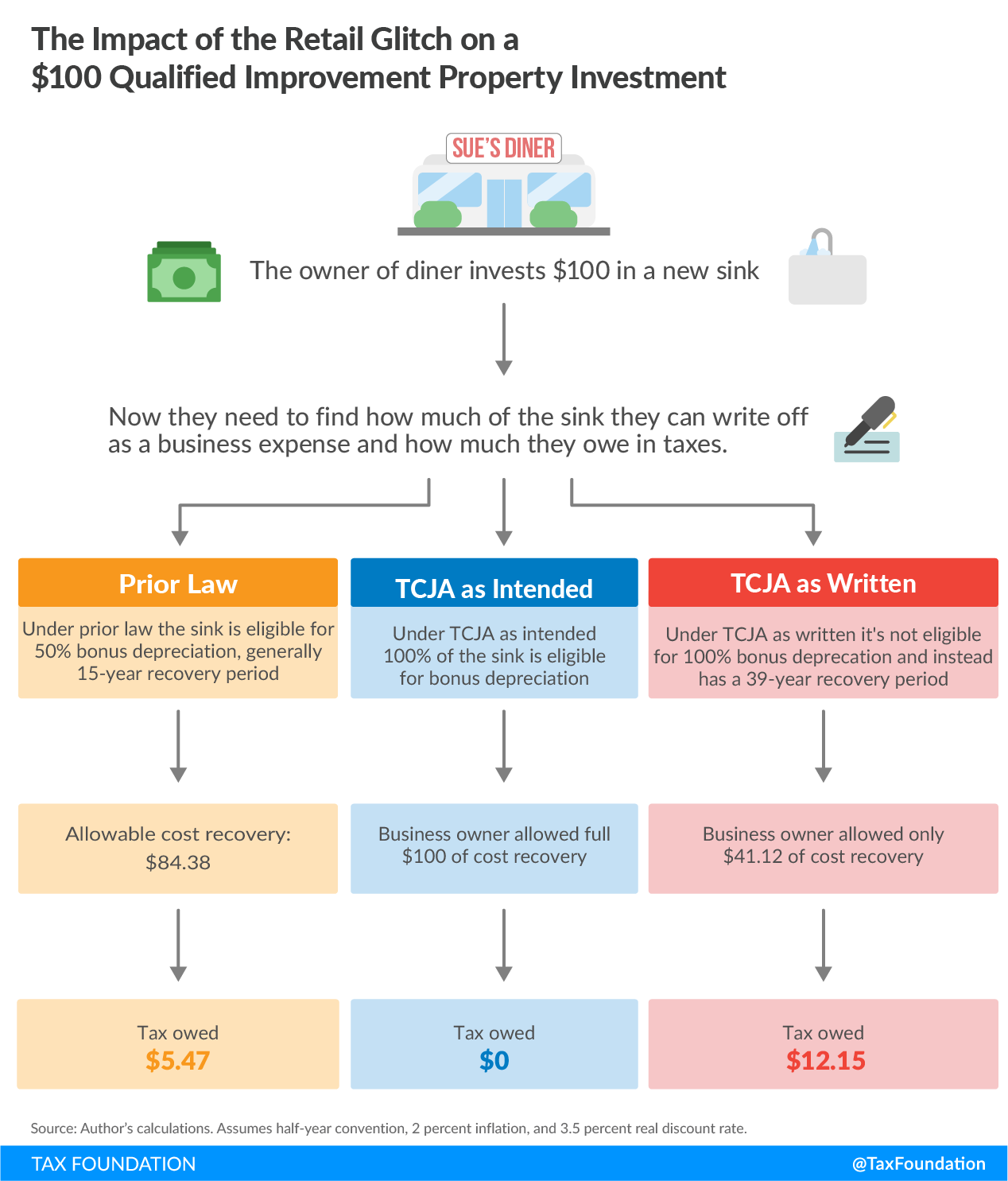

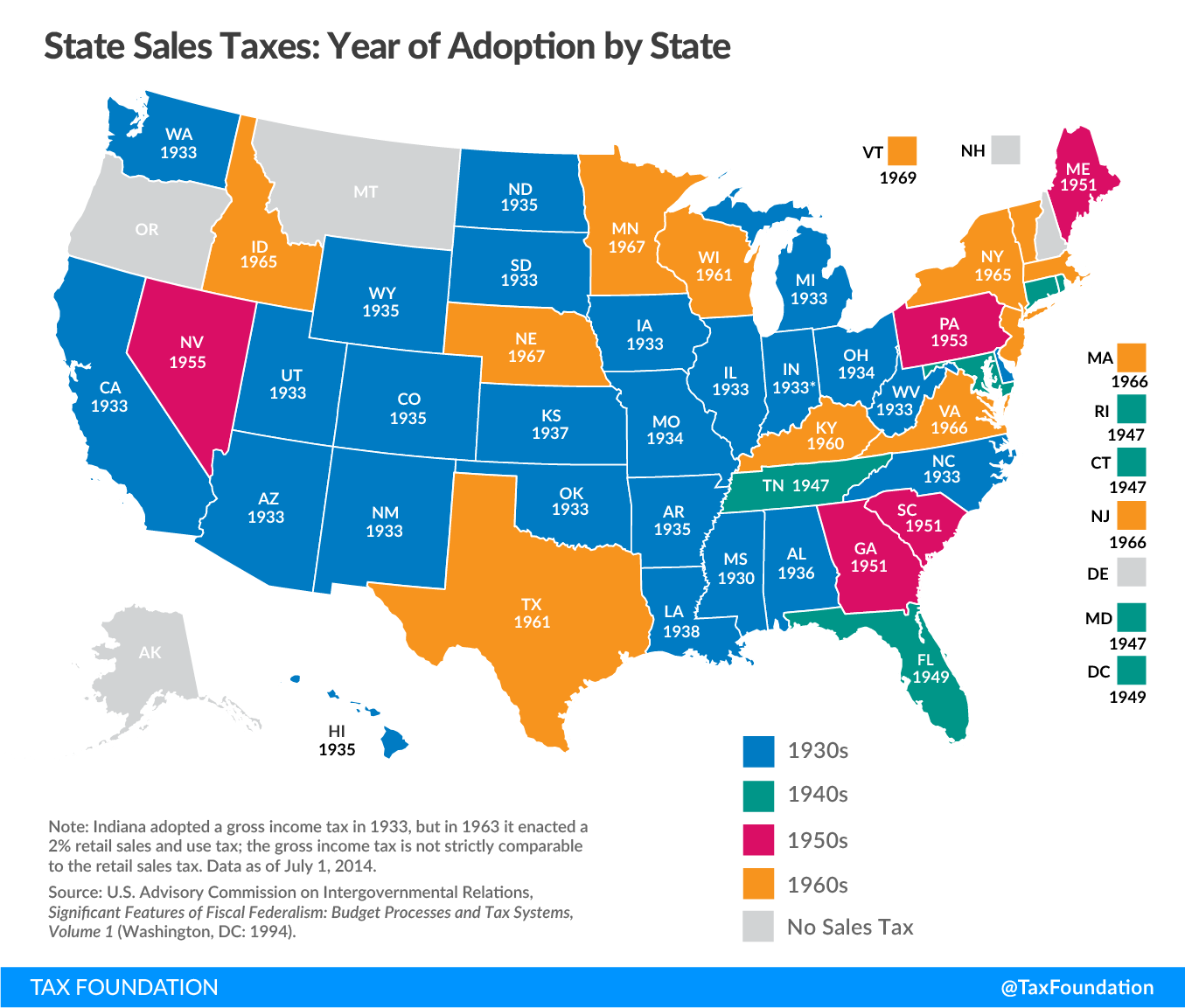

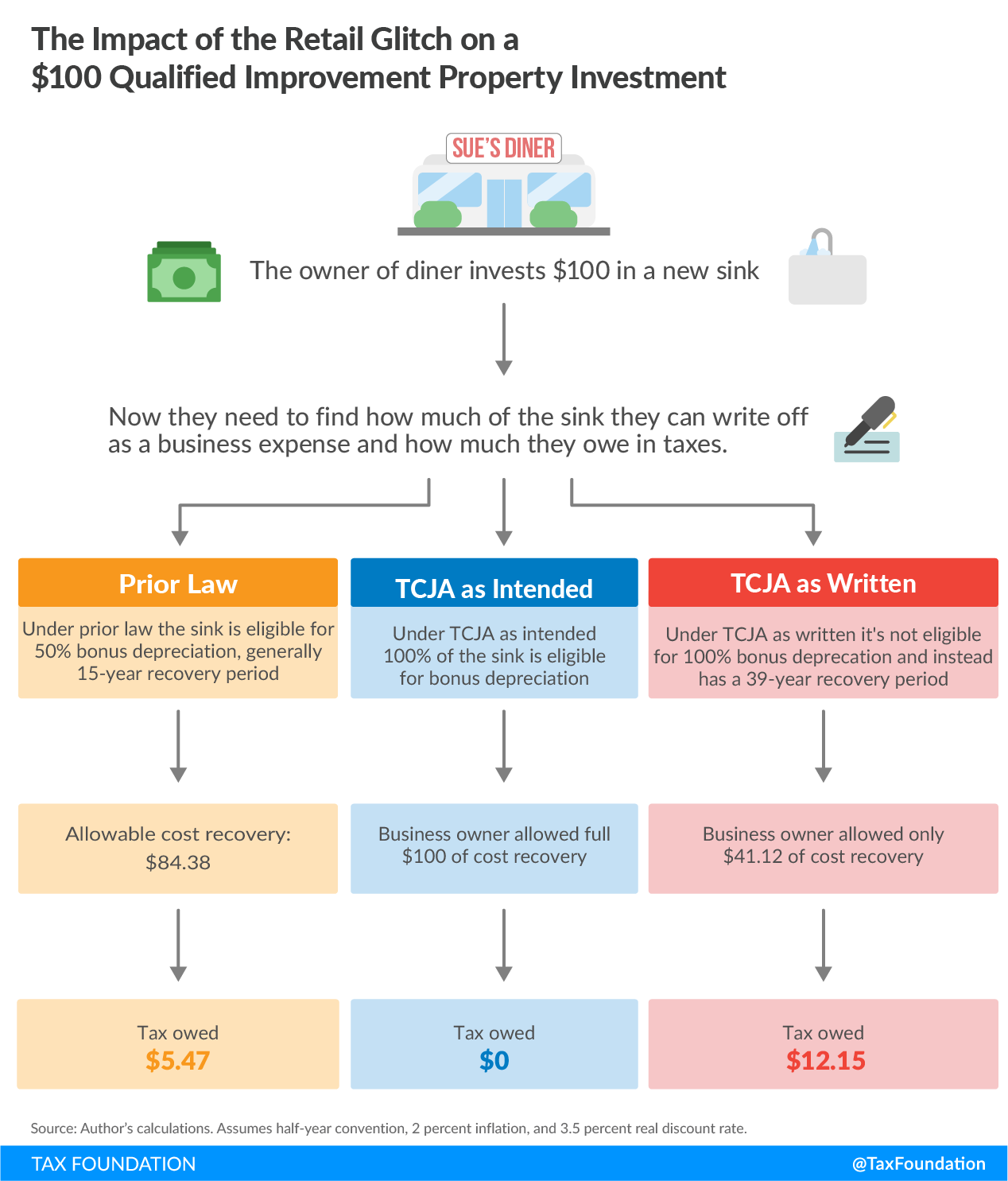

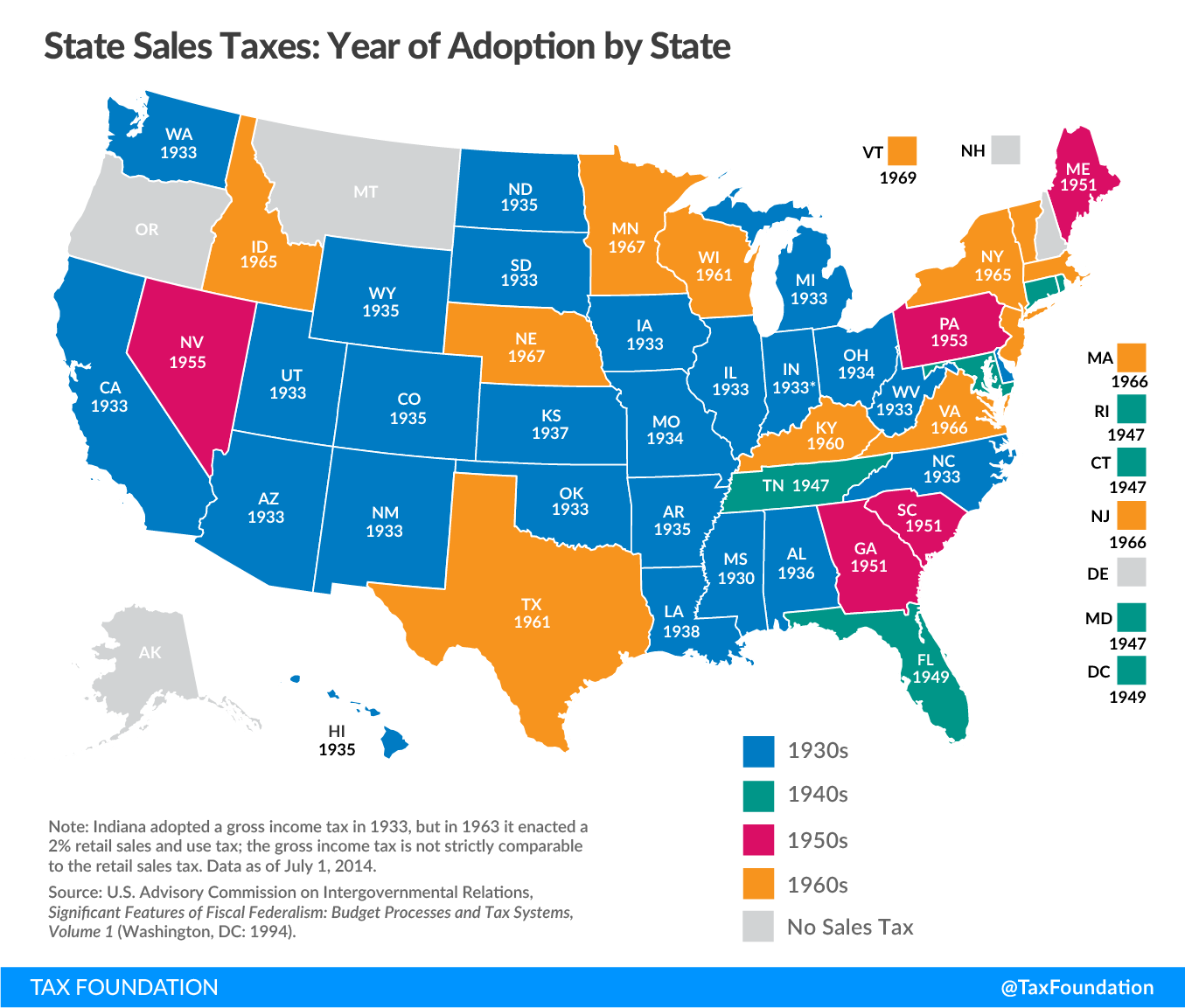

Correcting a historical accident means creating a broader tax base with lower rates

Utah originally adopted its sales tax in 1933, when the sale of tangible goods dominated United States consumer purchases and when the taxation of services would have been difficult to administer for undeveloped tax systems. The U.S. economy has since evolved, and the purchase of services now makes up more than two-thirds of all U.S. consumption. Yet many services are excluded from the sales tax base by this historical accident. The consumption tax base is eroded by omitting services, forcing policymakers to rely on less efficient forms of taxation.

The concept behind Utah’s proposed sales tax expansion is in line with sound tax policy. An economically neutral sales tax base should include the final retail sale of all goods and services purchased by end users. When retail service purchases are exempted from sales taxation, the result is a narrower tax base with higher tax rates falling largely on the goods-based economy.

Broadening the sales tax base and lowering sales and income tax rates would also create a more stable revenue source for funding government. Further, it would improve transparency in the tax code by taxing consumption more generally and can reduce the tax administration cost of distinguishing between taxable and nontaxable transactions. Utah lawmakers are on solid ground in their aim to expand the state sales tax to include more final retail sales. However, lawmakers should be careful to exempt business inputs from sales taxation lest the benefit of a broad tax base be undone by the harm of tax pyramiding on the multiple stages of business production.

Addressing business inputs and revenue triggers

All final consumption of goods and services should be taxed within a sales tax base. However, consumption by businesses should be exempted to avoid taxing products multiple times as a producer brings it to market. House Bill 441 S1 would impose a sales tax on a wide range of services for which a significant portion of purchases are business-to-business transactions rather than final retail sales. These services include sectors such as construction engineering, electrical and wiring contractors, plumbing and HVAC services, manufacturing, wholesale trade, air and bus transportation, freight trucking, credit intermediation, investment banking, and real estate brokerage.

Business-to-business transactions should be exempted from sales taxation to protect the transparency and neutrality of Utah’s tax code. If business inputs are taxed, then layers of taxes would stack up in each stage of production and add to final consumer cost, and might hamper the economic viability of some production processes. Additionally, final end-consumers would pay taxes upon taxes when they purchase a final product or service. This violates the principle of taxpayer transparency, because the end user would not see the several layers of taxation imputed into the final price of the product or service.

Furthermore, such tax layering creates a biased tax code. Products or services with longer production cycles would bear a disproportionate amount of the tax burden, creating the incentive for firms to vertically integrate in order to avoid the layers of taxation from making external purchases. Lawmakers have inherited a nonneutral tax code that favors service consumption over goods consumption. They should not correct this historical accident by favoring industries with shorter production cycles over those with longer production cycles, which is what taxing business inputs would do.

Lawmakers can consider replacing some of the revenues lost on business inputs by expanding the retail sales tax to apply to the consumption of fuel (which is subject only to an excise tax for funding public construction) and to groceries (which are subject to a reduced tax rate). The excise tax on fuel functions as a type of user-fee for funding public construction, which does not imply that retail fuels sales should be exempt from the general consumption tax. Furthermore, there are more targeted programs such as the earned income tax credit and grocery tax credit that can provide tax relief to low-income grocery shoppers while avoiding the revenue loss of a broad sales tax reduction.

One way to exempt businesses from being taxed on their inputs is to provide them with a sales tax exemption certificate. Utah already has such a structure set up for nonprofits and religious organizations which could be expanded to exempt business-to-business inputs.

Utah lawmakers can also protect against revenue volatility by enacting tax revenue triggers so that tax rates drop as revenue targets are met. A broad base expansion is a very positive reform, yet brings with it some uncertainty over when revenues will flow into state coffers as projected. This risk can be mitigated by making rate changes contingent upon meeting baseline revenue projections.

The next steps of tax reform

Utah can build upon a strong legacy of tax reform and step forward in modernizing its sales tax by expanding its sales tax to the consumption of both final goods and services while exempting business inputs from sales taxation.

Utah ranks #8 on the Tax Foundation’s 2019 State Business Tax Climate Index, and could potentially improve its ranking with a well-structured sales tax reform. Utah’s sales tax ranking is its weakest component in the Index, which penalizes states for having too narrow a sales tax base and for layering taxation upon business inputs.

Utah in the 2019 State Business Tax Climate Index (SBTCI) rankings by Area

| Overall Rank |

Corporate Tax Rank |

Individual Income Tax Rank |

Sales Tax Rank |

Property Tax Rank |

Unemployment Insurance Tax Rank |

| 8 |

5 |

10 |

16 |

3 |

16 |

Utah could improve its economic competitiveness, and thus its Index ranking, by enacting an ideal sales tax reform. Utah’s ranking would move from 16th to 6th on sales taxation and 8th to 5th overall by extending the sales tax to all final consumption while exempting business inputs and marginally reducing rates.

Utah’s Projected Rankings in the SBTCI after Enacting Ideal Sales Tax Reform

| Overall Rank |

Corporate Tax Rank |

Individual Income Tax Rank |

Sales Tax Rank |

Property Tax Rank |

Unemployment Insurance Tax Rank |

| 5 |

5 |

10 |

6 |

3 |

16 |

While Utah’s legislative session ends March 14th, tax reform is an ongoing process to be continued in a future legislative session. Utah’s next steps in tax reform will show how well a state can manage the trade-offs of enacting an ideal sales tax.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Utah Proposal to Modernize State Sales Should Avoid Layering Taxes on Business Inputs

TAXTIMEKC

TAXTIMEKC