by r Hampton | Mar 7, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Washington Capital Gains Proposal Not Helped by Analogy to Real Estate Excise Tax

Proponents of a capital gains tax in Washington have long sought to argue that the tax can be designed as an excise tax rather than an income tax, to avoid constitutional constraints imposed on income and property taxation in the state. We’ve written in the past about how this is inconsistent with plain definitions as well as the way capital gains are taxed in other states and at the federal level (always under the individual income tax) and misstates what constitutes an excise tax. Most recently, however, proponents seem to be centering their argument on a notion advanced in a 2011 memo developed for them, which argues that precedent for such a tax exists in the form of the state’s real estate excise tax. But does it really?

Washington’s real estate excise tax is a tax on the transfer of real property (called a real estate transfer tax in many states), levied at a state rate of 1.28 percent, plus local rates which vary by jurisdiction. The tax is imposed on the privilege of transferring the property and falls on the entirety of the sale price.

This fits the definition of an excise tax. Such taxes fall on specific goods or services and—most importantly—they’re based on sales, either denominated in price or volume. As we’ve noted previously, that’s not how capital gains taxes work. They’re not levied at a set rate on each financial transaction. Rather, they’re imposed on the net income from investments when that income is realized.

However, according to the authors of the memo, even if an income tax is off limits (proponents would like to revisit the state supreme court decisions surrounding the state’s uniformity clause), a capital gains tax shares the characteristics of the court-approved real estate excise tax:

In my opinion, a capital gains tax is distinct from a property tax (or, under Culliton, an income tax qua property tax) in that it is not an unavoidable annual tax on an asset, or even an annual tax on personal income, but instead is, as Justice Tolman put it, a tax on the gains from property or investment, gains that could not be enjoyed without the benefits of government. A capital gains tax, collected when the sale of property is made and a profit is realized, is conceptually the same as the real estate excise tax imposed under Chapter 82.45 RCW, a tax which was upheld as an excise tax by the Washington State Supreme Court soon after its enactment. Mahler v. Tremper 40 Wn.2d 405, 243 P.2d 627 (1952). In Mahler, the Court pointed out that the real estate excise tax was not a tax on the enjoyment or use of one’s property, as is the case of the annual property tax. Instead, that tax was imposed on the one-time “act or incidence of transfer.” 40 Wn.2d at 409-410. Similarly, a capital gains tax is not imposed on the property itself or on the enjoyment of it. Instead, it is imposed on the single sale of the asset, measured as a percentage of the gain.

That last clause, “measured as a percentage of the gain,” is doing a lot of work here.

A real estate transfer tax is levied on the entire sale price of the property. Capital gains taxes are on the net of gains and losses, across many transactions. As we’ve observed in the past, if there were an excise tax on the privilege of buying or selling stocks or other investment assets, it would fall on the entirety of the sale price of each asset, not on the net of gains and losses across all investments. The proponents’ example doesn’t solve this problem—it underscores it.

A real estate transfer tax does not, after all, just capture any return on an investment in a property which has appreciated (or, conversely, any loss from one which has declined in value). It captures the entire sale price. But there actually is a tax that falls on the net gain from the sale of real property, and it’s called: the capital gains tax!

Yes, capital gains on real estate are taxable under the federal income tax. There are significant exclusions which prevent the tax from falling on most sellers (the first $250,000 in gains are exempt for single filers, or $500,000 for joint filers), but beyond the exclusion amount, the net of gains from real estate are taxed—as capital gains. This is clearly and fundamentally distinct from real estate excise (or transfer) taxes, which are imposed on the full sale price.

Proponents seem to believe that the existence of the real estate excise tax is crucial to their legal argument. If so, that’s probably not good news for them, because the analogy falls flat. The key feature of capital gains taxation, what makes it income, is in the way it diverges from the real estate excise tax: it’s “measured as a percentage of the gain,” as the proponents’ memo puts it. There’s a word for that tax base. It’s income.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Washington Capital Gains Proposal Not Helped by Analogy to Real Estate Excise Tax

by r Hampton | Mar 7, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Utah Contemplates 86 Percent Tax on E-Cigarettes

Utah’s cigarette tax rate hews closely to the national average; its smoking rate does not. Fewer than 9 percent of Utah adults are smokers, the lowest smoking rate in the country by a comfortable margin. And about half of them are trying to quit. But one harm reduction and (for some smokers) tobacco cessation option might become far costlier in Utah, should pending legislation on the taxation of e-cigarettes and vapor products be enacted.

Under House Bill 252, electronic cigarettes and other vapor products would be taxed at a rate of 86 percent of the manufacturer’s sales price, which would represent one of the highest taxes in the nation, and which is significantly out of line with taxation of traditional cigarettes. It is instead aligned with the tax on other tobacco products like chewing tobacco, snuff, and “dissolvables.” The tax is projected to raise $23.6 million a year.

Eleven states and the District of Columbia tax vapor products, three of which only have a local tax in select jurisdictions. Six states impose specific excise taxes, meaning that the taxes are denominated as a particular amount on a given unit of product—in the case of e-cigarettes, cents per fluid milliliter. The remaining states or localities (and D.C.) impose ad valorem taxes, meaning that the tax falls on the wholesale price of the product.

The table below shows the existing statewide excise taxes on vapor products. Additionally, local taxes are imposed in certain jurisdictions in Alaska, Illinois, and Maryland.

| State |

Tax Rate |

| California |

62.78% of wholesale |

| Kansas |

$0.05/ml |

| Louisiana |

$0.05/ml |

| Minnesota |

95% of wholesale |

| New Jersey |

$0.10/ml |

| North Carolina |

$0.05/ml |

| Pennsylvania |

40% of wholesale |

| West Virginia |

$0.075/ml |

| District of Columbia |

96% of wholesale |

Excise taxes differ from the general sales tax inasmuch as they target specific products or transactions. This is typically justified as a user-pays model (as with the gas tax, which corresponds—if imperfectly—with a driver’s contribution to congestion and road wear-and-tear) or as a way to capture negative externalities, such as increased state health costs. In the case of those excise taxes often thought of as “sin taxes,” the tax, by increasing the cost of the product, is also intended as a disincentive, designed to reduce consumption.

E-cigarettes are relatively new, and states have struggled to determine if and how to tax them. When smokers shift to vapor products, this reduces cigarette tax revenue, but given that a stated purpose of most tobacco taxes is to improve health outcomes and reduce health-related expenditures, the harm reduction associated with these alternative products must be taken into account.

The scientific literature demonstrates that vapor products are a less harmful alternative to traditional cigarettes, and that they can thus serve as an important harm reduction option for existing smokers, or even as a pathway to giving up smoking altogether. If a major purpose of the tax is to improve health outcomes, one would expect e-cigarettes to be taxed less than traditional tobacco products, if at all (beyond the general sales tax). Under the legislation pending in Utah, however, the opposite would be true.

As an ad valorem tax, moreover, the tax contemplated under H.B. 252 would fall not only on the e-cigarette fluid itself, but also on the delivery mechanism when the two are sold together. This has the effect of taxing single-use disposable e-cigarettes at a higher rate than rechargeable and refillable devices, which may hit lower-income individuals the hardest, since lower-income consumers may be less likely to purchase rechargeable devices.

Finally, to the extent that Utah is counting on the revenue from an e-cigarette tax, sales of all tobacco products are declining, and there is little reason to believe that this trend won’t ultimately extend to vapor products as well—even if, for now, their market share is growing as consumers shift from traditional tobacco products. That transition to less harmful products, however, may be less pronounced (to the detriment of existing smokers) if the state chooses to impose a disproportionately high tax on the alternative.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Utah Contemplates 86 Percent Tax on E-Cigarettes

by r Hampton | Mar 7, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Who Benefits from Itemized Deductions?

The tax code contains more than 170 preferences that benefit individuals, varying from credits to deductions to exclusions, which were projected to cost $1.3 trillion over the last fiscal year. The tax code remains progressive after accounting for these provisions. However, certain provisions, such as itemized deductions, primarily benefit higher-income households.

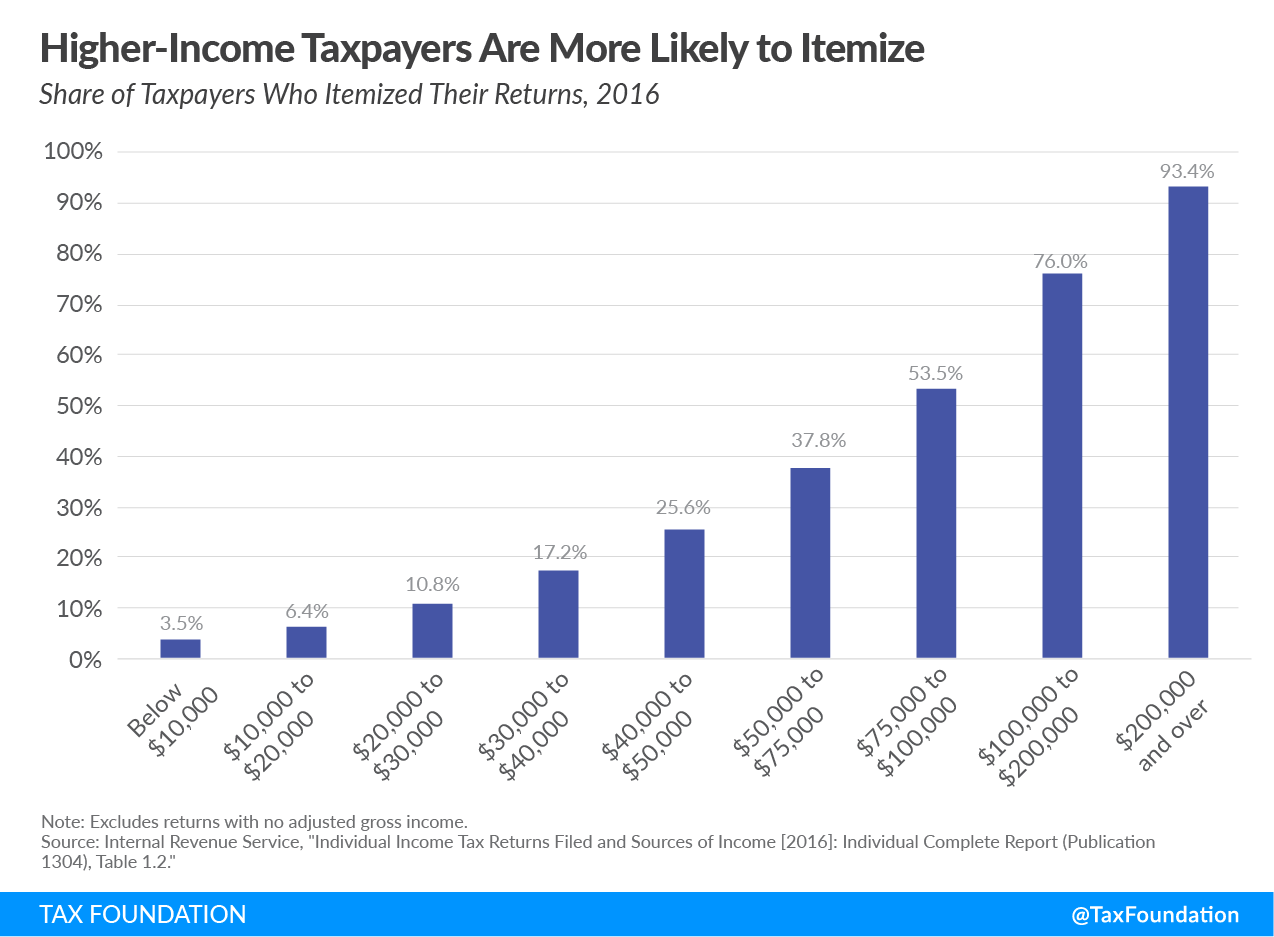

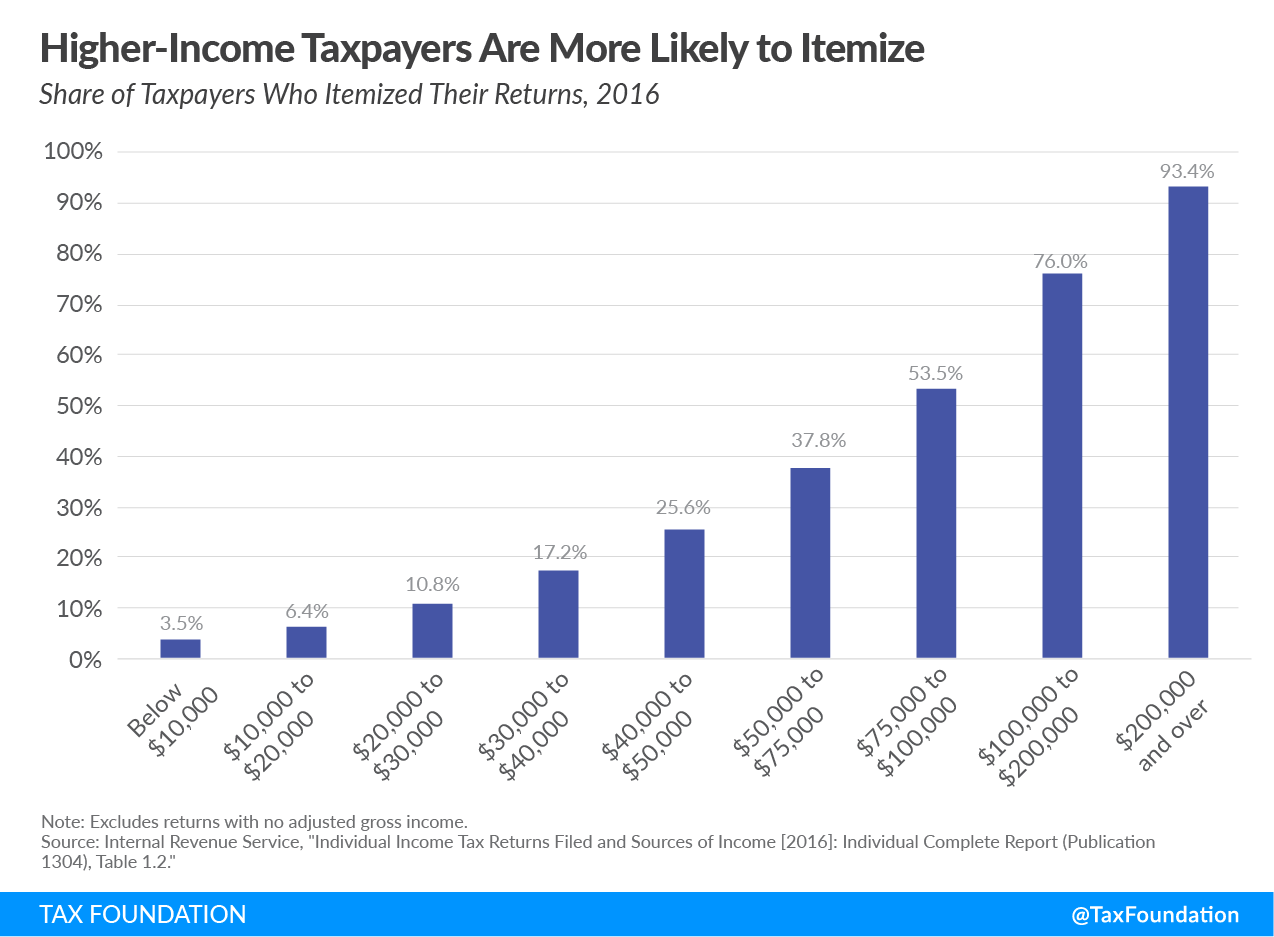

The chart below uses data from the Internal Revenue Service to examine who claimed itemized deductions in 2016. Note that this was before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) made changes which limited certain itemized deductions and expanded the standard deduction.

The percentage of taxpayers who itemize increases as we move up the income scale. In 2016, barely a quarter of households with adjusted gross income (AGI) between $40,000 and $50,000 claimed itemized deductions when filing their taxes. In contrast, more than 90 percent of households making $200,000 and above itemized their deductions.

This is important because the value of deductions depends on the top tax rate a taxpayer pays. For example, a $1,000 deduction is worth $220 for someone in the 22 percent tax bracket. The same $1,000 deduction would be worth $370 to someone in the 37 percent bracket.

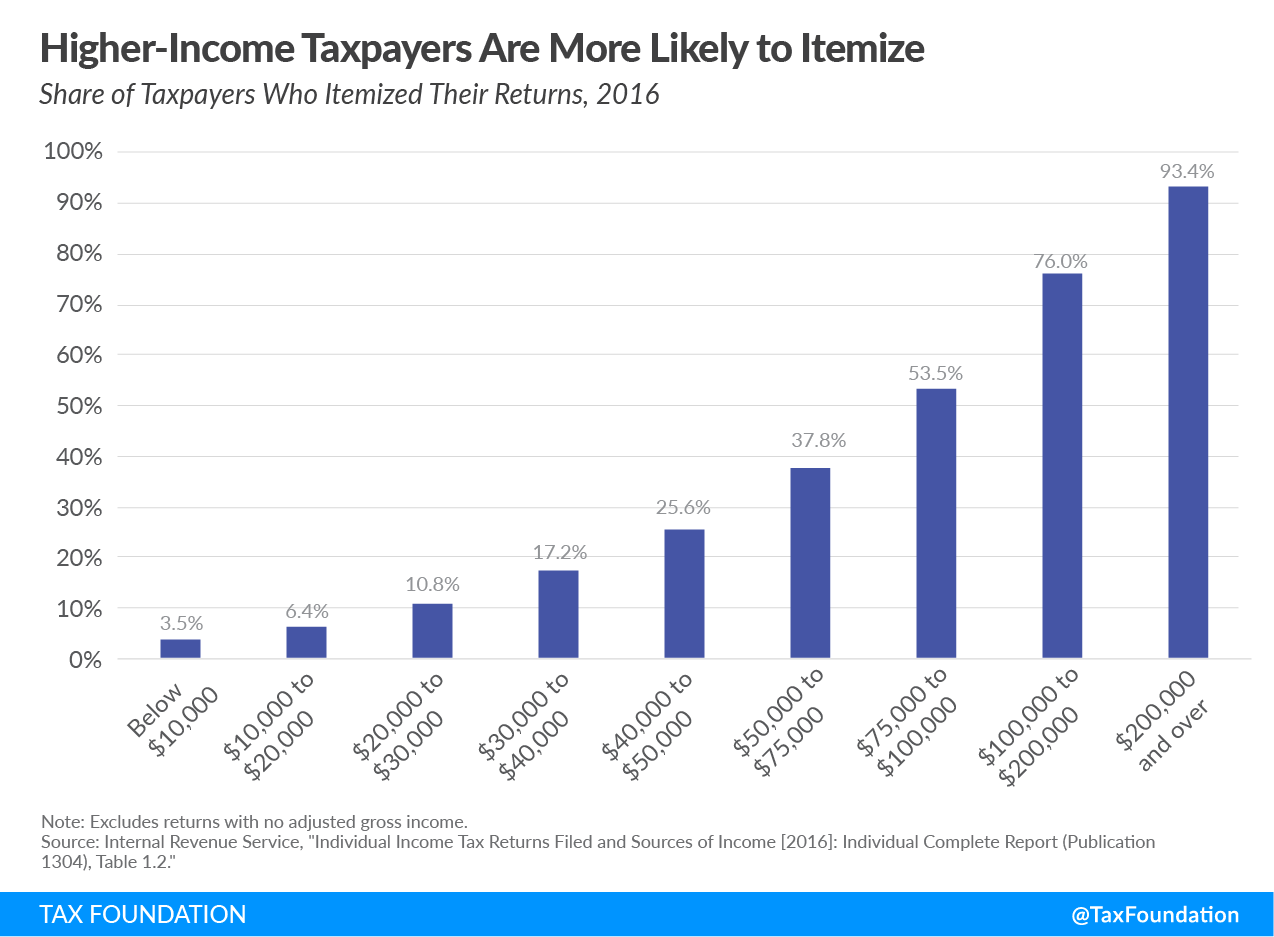

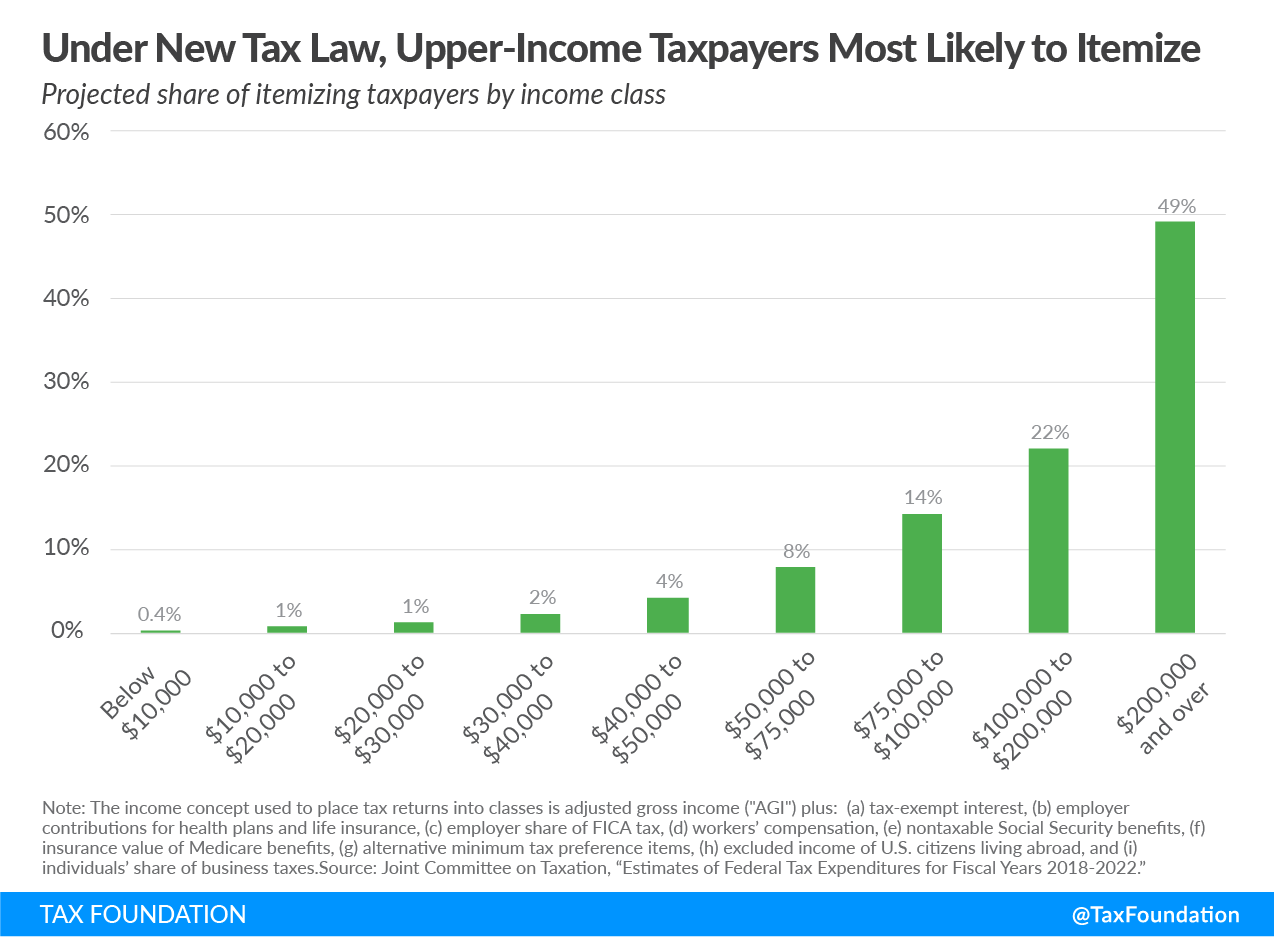

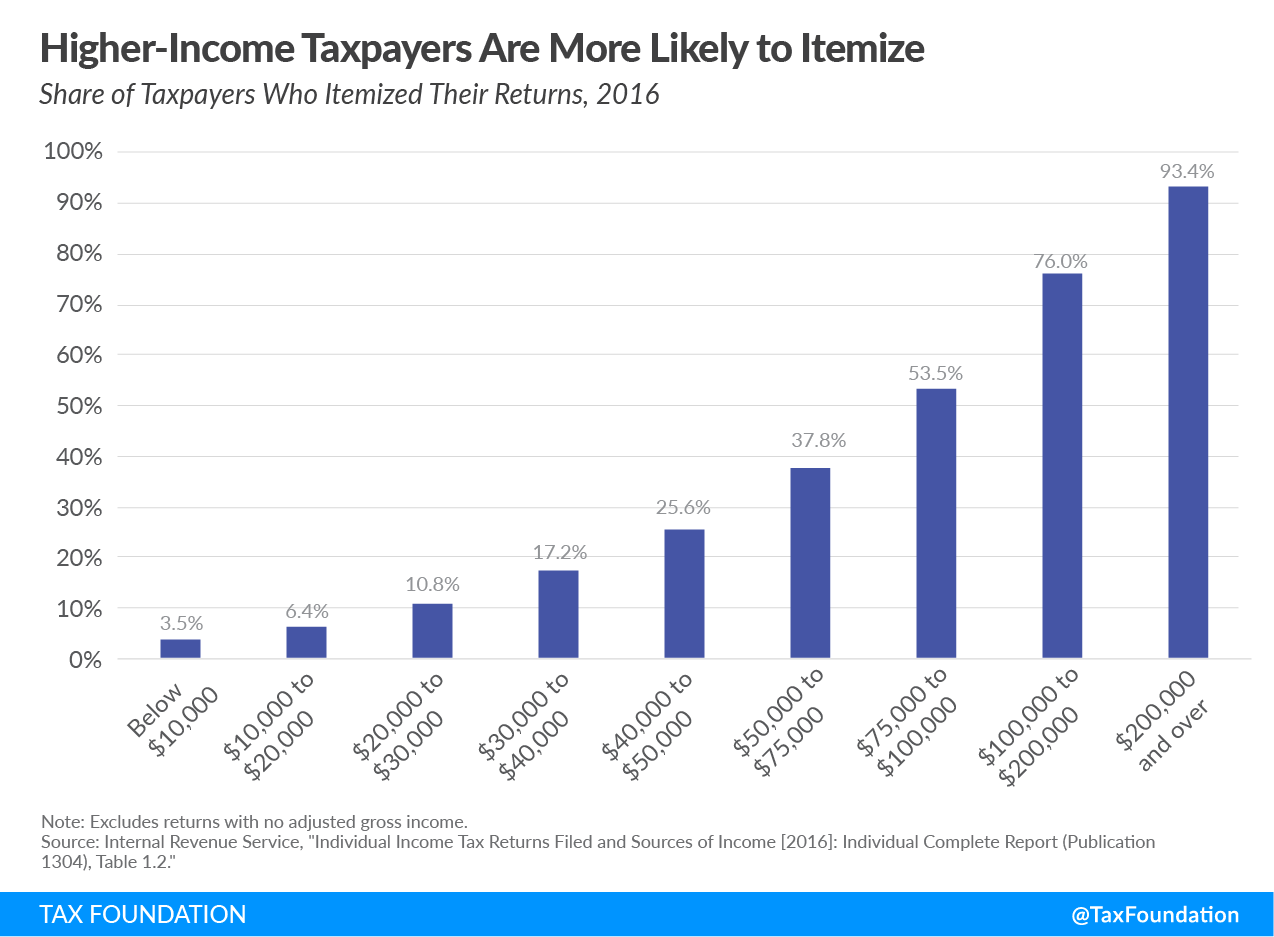

In the coming years, fewer taxpayers will itemize their deductions, instead opting to take the TCJA’s newly expanded standard deduction. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that the number of filers who itemize would fall from 46.5 million in 2017 to just over 18 million in 2018, the year the changes took effect.

The JCT has also projected that the benefit of itemized deductions will increasingly flow to higher-income taxpayers. Projections for 2018 show that just 8 percent of filers making between $50,000 and $75,000 will itemize, compared to nearly half of taxpayers making $200,000 and over. Comparing the 2016 data with these 2018 data shows that, as mentioned above, changes in the TCJA will lead to fewer taxpayers claiming itemized deductions, and that those who continue to itemize will be higher-income households.

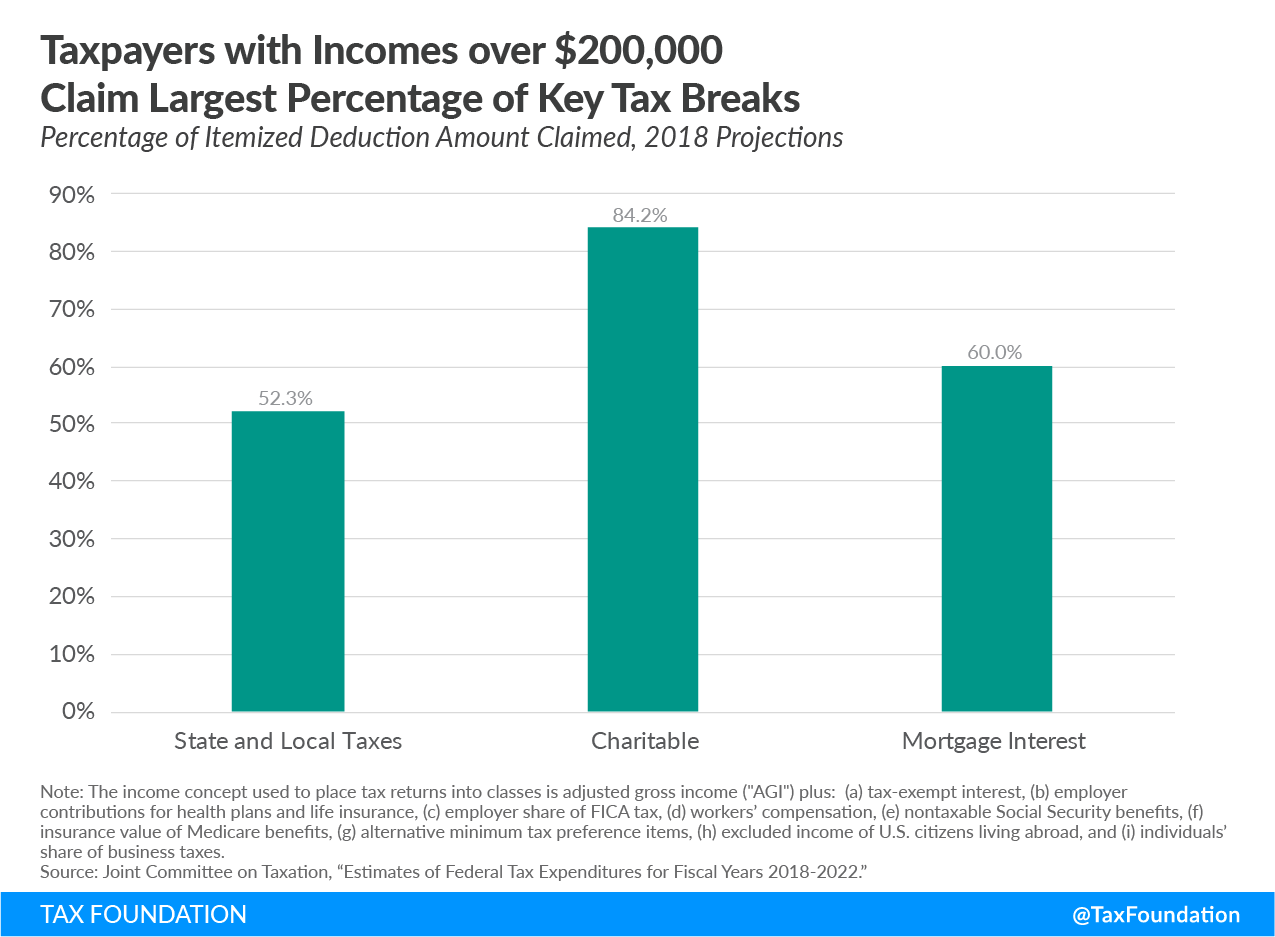

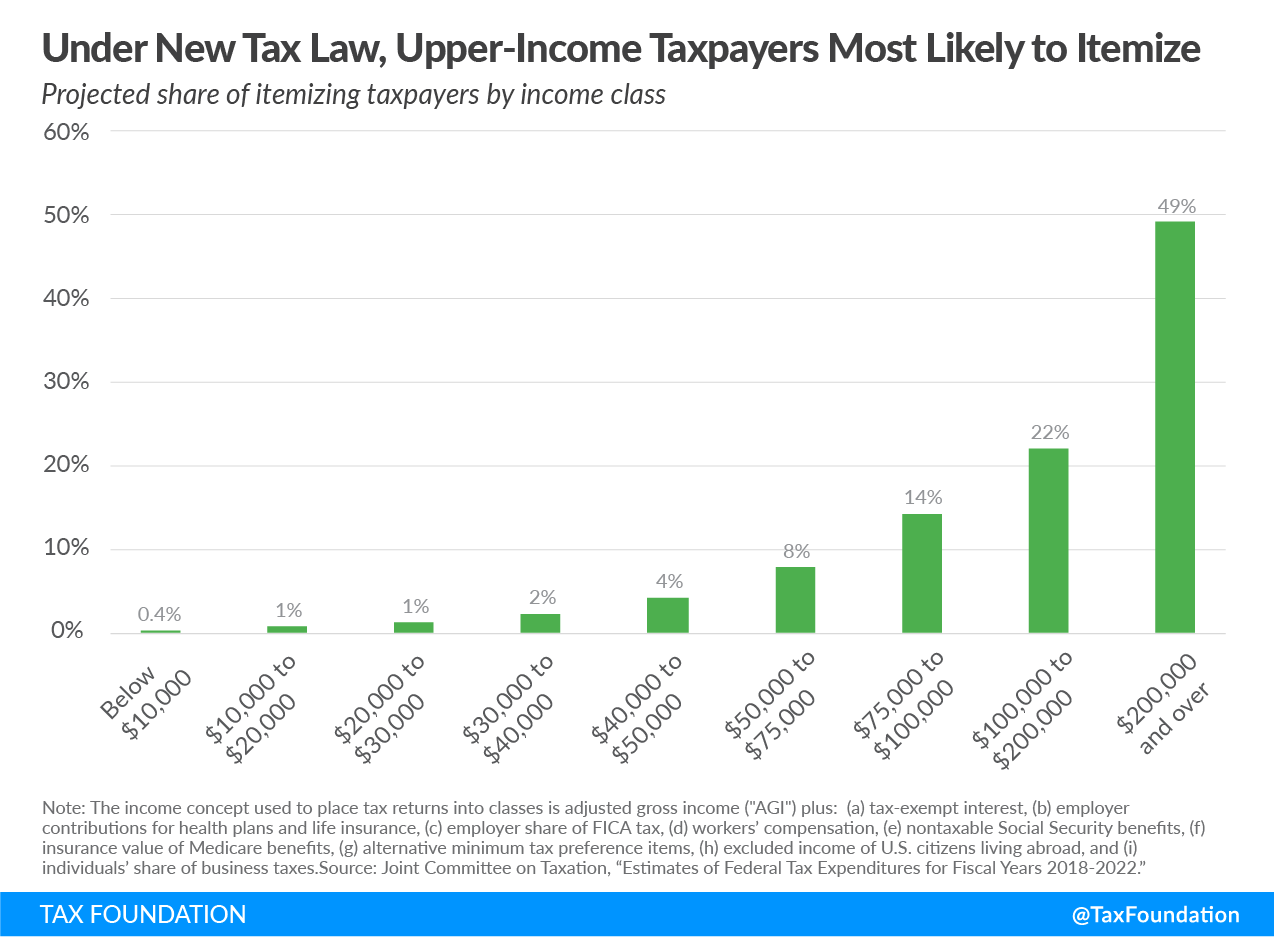

In 2018, the mortgage interest deduction was estimated to cost $33.7 billion, the deduction for state and local taxes paid $43.1 billion, and the charitable contributions deduction $40.6 billion. Though lawmakers have enacted limitations to reduce the value of tax deductions, taxpayers earning more than $200,000 still claim a disproportionately large share of certain key tax breaks.

According to the JCT, high-income taxpayers will claim 52 percent of the state and local tax deduction, 84 percent of the charitable donation deduction, and 60 percent of the mortgage interest deduction.

While the tax code contains preferences that benefit lower- and middle-income households, such as the earned income credit and the child tax credit, others, like itemized deductions, primarily benefit high-income households. Even so, the overall burden of the individual income tax remains progressive.

Note: This is part of a blog series called “Putting a Face on America’s Tax Returns”

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Who Benefits from Itemized Deductions?

by r Hampton | Mar 7, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – New Mexico Tax Increase Package Advances

Under New Mexico’s last two governors, the state cut both individual and corporate income tax rates. Legislation backed by Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham (D) would not only reverse course but make New Mexico a regional outlier, with higher and more progressive income taxes than any of its neighboring states. It’s part of a broader package that also includes:

- an expansion of the sales tax to capture remote sellers;

- a cigarette tax increase, from $1.62 to $2 per pack;

- an increase in the tobacco products tax, from 25 to 45 percent, with the definition of taxable tobacco products expanded to include e-cigarettes and other vapor products;

- an increase in the motor vehicle excise tax to 4 percent; and

- a new tax on nonprofit hospitals.

Notably, it comes as the state is running a large surplus.

House Bill 6 passed that chamber on a 40-25 vote and is now pending in the Senate. If enacted, it would raise taxes by $580 million a year. The state is currently projecting a $1.1 billion surplus, but proponents see the bill as an opportunity to increase the share of tax collections from sources other than the state’s energy industry, which can be volatile and unpredictable. New Mexico is eighth in the nation in energy production, and generated $2.2 billion in government revenue from fossil fuel production in fiscal year 2018. The state’s current energy boom is welcome news to budget writers but adding it all to the baseline can be risky, as there is no guarantee that oil and gas prices (or in-state production) will be as strong in future years.

That’s a strong case for enhancing the state’s rainy day and other funds, setting more money aside in good years to provide a cushion in leaner ones. To proponents of H.B. 6, the volatility of energy markets is also a reason for New Mexico to chart a different course than its neighbors—many of which are also major energy-producing states. (Texas, Oklahoma, and Colorado rank 1st, 4th, and 7th, respectively on that measure.)

In 2003, New Mexico’s top individual income tax rate was 8.2 percent, and newly-elected Gov. Bill Richardson (D) set out to change that in an attempt to put the state on a more competitive footing with its peers. A five-year individual income tax cut package, with implementation beginning the next year, ultimately transformed a seven-bracket tax with a top rate of 8.2 percent into a four-bracket tax with a top rate of 4.9 percent. A decade later, Richardson’s successor, Gov. Susana Martinez (R), embarked on a similar phased reduction in the corporate income tax, reducing the top rate from 7.6 percent in 2013 to 5.9 percent by 2018.

| Individual Income Tax |

|

Corporate Income Tax |

| Year |

Brackets |

Top Rate |

|

Year |

Brackets |

Top Rate |

| 2003 |

7 |

8.2% |

|

2013 |

2 |

7.6% |

| 2004 |

6 |

7.7% |

2014 |

2 |

7.3% |

| 2005 |

5 |

6.8% |

2015 |

2 |

6.9% |

| 2006 |

4 |

5.7% |

2016 |

2 |

6.6% |

| 2007 |

4 |

5.3% |

2017 |

2 |

6.2% |

| 2008 |

4 |

4.9% |

2018 |

2 |

5.9% |

Neighboring states cut taxes too. Arizona adopted seven income tax rate reductions between 1990 and 2007, lowering its top rate from 7 to 4.54 percent. Colorado abandoned its graduated-rate income tax structure, with a top rate of 8 percent, in 1987, replacing it with a flat rate tax that was cut to 4.75 percent in 1999 and to its current rate of 4.63 percent in 2000. Oklahoma phased its top rate down from 6.65 to 5.25 percent between 2004 and 2007 and adopted another reduction—to 5 percent—in 2014. And in Utah, a 2007 tax overhaul scrapped a six-bracket system with a top rate of 7 percent for a flat 5 percent rate, trimmed to 4.95 percent in 2018. Texas and Nevada both forgo individual income taxes altogether. For the past five years, neither New Mexico nor any of its neighbors have imposed an income tax rate of more than 5 percent.

That would change under H.B. 6, which returns to a seven-bracket individual income tax structure with a top rate of 6.5 percent. Moreover, while that top rate would not kick in until $200,000 in taxable income for single filers ($300,000 for joint filers), it would increase income tax burdens for many New Mexicans. Overall tax liability is almost identical for the lowest-income taxpayers; between about $10,000 and $23,500 in taxable income, it represents annual tax savings of about two dollars per taxpayer. (Some filers would, however, benefit from other provisions.) Above $30,000 in taxable income, it represents a tax increase. That increase grows rapidly. Take, for instance, a single individual earning the state’s average household income of $46,744, with taxable income of $34,544 after taking the standard deduction. Under H.B. 6, her income taxes go up by more than a third, from $1,070 to $1,429. Someone with $50,000 in taxable income would experience a 61 percent increase in tax liability, from $1,387 to $2,233.

The following tables show how rates and brackets change for single filers under the proposal.

| Current Law |

|

H.B. 6 Proposal |

| 1.7% |

> |

$0 |

|

1.7% |

> |

$0 |

| 3.2% |

> |

$5,500 |

3.2% |

> |

$6,650 |

| 4.7% |

> |

$11,000 |

4.7% |

> |

$10,000 |

| 4.9% |

> |

$16,000 |

5.2% |

> |

$23,500 |

| |

5.5% |

> |

$50,000 |

| 5.8% |

> |

$100,000 |

| 6.5% |

> |

$200,000 |

These aren’t just tax increases on high earners; they would have a dramatic impact on middle-class New Mexicans. However, increases are ameliorated for some filers by various changes. The state’s standard deduction and personal exemption conform to those offered by the federal government, and under the new federal tax law, the standard deduction almost doubled (to $12,200 for 2019) but the personal exemption has been suspended. The proposal, while retaining the higher standard deduction, creates a state-specific dependent deduction worth $4,000 for their second and subsequent dependents. (No deduction is available for the first dependent claimed.) This depended deduction would be available so long as the federal personal exemption is suspended. The Working Families Tax Credit, moreover, increases from 10 to 20 percent of the value of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

New Mexico’s income tax has long included a marriage penalty, meaning that in many cases, married two-earner households pay more in taxes than they would if they were filing separately. (States can avoid a marriage penalty by doubling bracket widths for joint filers, but while joint filer brackets are wider than single filer brackets in New Mexico, they aren’t twice as wide.) Under the current tax code, however, the impact is modest: the most a couple could pay in marriage penalties is $151. Under H.B. 6, that would soar to a maximum of $1,111.

Under current law, the first $1,000 in capital gains are excluded from taxation, and a 50 percent deduction is available for remaining capital gains income, consistent with the federal policy of preferential rates for capital gains. Such a policy favors investment but is also intended to compensate for the degree to which inflation erodes the value of capital gains. Imagine, for instance, a $10,000 investment made twenty years ago and sold for $20,000 in 2019. This represents a nominal gain of $10,000, but about $5,110 of that is a phantom gain; it’s just the effects of inflation. In real terms, the investment returned $4,890. Absent any preferential rate for capital gains income, however, the entire $10,000 “gain” would be taxed. A preferential rate or deduction is a crude way to address this issue, but nevertheless serves a valuable purpose. Under H.B. 6, the $1,000 exclusion is maintained, but the 50 percent deduction would be repealed.

The bill would also tax internet sales beginning July 1 of this year, and ultimately change how the state imposes its sales tax. New Mexico’s sales tax—confusingly termed a “gross receipts tax,” even though it is not structured like the gross receipts taxes that exist in certain other states—is origin- rather than destination-sourced, meaning that the tax is levied at the seller’s location, not the buyer’s, and is subject to the local rate in the seller’s jurisdiction. For remote transactions already subject to tax due to the seller’s physical presence in the state, the state sales tax is destination-sourced, but the remote seller does not owe local sales taxes. Under H.B. 6, the state would begin a two-year transition, ultimately resulting in destination-sourced local sales taxes for remote sales. In the interim, the bill provides for transfers to local governments to allow them to share in the new revenue.

Notably, New Mexico does not adhere to the uniformity and simplification rules provided for in the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement (SSUTA). It has not adopted the common definitions employed in member states, nor does it provide rate and base lookup software for the sales tax as it exists statewide and in the state’s 144 local taxing jurisdictions. Taking these modest steps would help ensure that the state’s remote sales tax regime is consistent with the standards praised by the U.S. Supreme Court in Wayfair v. South Dakota, and thus likely to survive any legal challenge.

Historically, New Mexico has lagged its peers in gross state product and job growth, with spurts in both when energy markets are particularly strong. Taxes are only one of many considerations for individuals and businesses, but for a state surrounded by faster-growing peers, a package of significant tax hikes poses real risks.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – New Mexico Tax Increase Package Advances

by r Hampton | Mar 6, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – There are Better Ways to Raise Revenue in Oregon Than a Gross Receipts Tax

This week, Oregon’s Legislative Revenue Office (LRO) provided economic projections to the Joint Committee on Student Success Subcommittee on Revenue to assess the impact of a proposed gross receipts tax on Oregon’s economy. The committee is interested in raising about $1 billion in annual revenue from a new source to improve the state’s public education system. This is the third time Oregon has considered a gross receipts tax in the past five years, after a legislative proposal failed in 2017 and a ballot initiative to enact a gross receipts tax was rejected by voters in 2016.

LRO modeled a gross receipts tax similar to Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax, levied at 0.48 percent of a firm’s gross receipts above $1 million in Oregon, plus a $250 minimum tax on all firms. The petroleum sector is exempted from the proposal, as petroleum is governed under an industry-specific tax regime in Oregon. The proposal also calls for the use of some of the revenue from the gross receipts tax to reduce Oregon’s personal income tax rates:

Oregon 2019 and Proposed Personal Income Tax Rates (Filing Single)

| Tax Bracket |

2019 Tax Rate |

Proposed Tax Rate |

| Taxable income over $0 |

5.0% |

4.5% |

| Taxable income over $3,450 |

7.0% |

6.5% |

| Taxable income over $8,700 |

9.0% |

8.75% |

| Taxable income over $125,000 |

9.9% |

9.9% |

LRO provided two simulations to estimate the impact of the new gross receipts tax and personal income tax rate reductions on, among other indicators, state revenue, household income, employment, and wages over five years. The projection combines the effects of both the gross receipts tax and the changes to personal income tax rates, which will have different economic impacts. The gross receipts tax is expected to lower economic output, raise prices, and harm job creation, while a reduction in personal income tax rates would help economic growth by increasing the incentive to work and invest in Oregon.

The first simulation found that household income would fall by 0.3 percent across every income level, and the state would lose about 8,400 full-time equivalent jobs, a decrease of 0.31 percent. Revenue increases by about $1.1 billion annually, though $27 million is lost due to the negative economic impacts of the gross receipts tax. Investment would decline by 0.06 percent.

LRO also provided a second simulation, which incorporates the new spending on education made possible from gross receipts tax revenue. The model finds that the spending improves long-run labor force productivity, raising the state’s economic growth. It assumes that as the new revenue is used on education, new entrants into the labor force are made more productive through a higher quality public education.

In contrast to the first model, the second simulation finds that Oregon’s disposable household income rises on average by 0.3 percent. However, lower-income households see a fall in their incomes by 0.1 percent to 0.2 percent. Job creation also suffers, as 3,000 net fewer jobs are created. Under this model, Oregon is expected to raise about $1.34 billion in revenue, including $212 million from additional economic growth stemming from improved labor force productivity.

Both models are useful for understanding the impact of the two changes to Oregon’s tax code on the state’s economy. However, it’s important to note that the economic growth found in the second simulation is the result of an improved education system and not from imposing a gross receipts tax. There are better and worse ways for Oregon to raise a given amount of revenue, and we would expect economic growth to be larger if policymakers use a more efficient method to raise revenue for the education system. The first simulation provides a better perspective on the direct effects of a gross receipts tax, though the negative effects are somewhat mitigated by the reduction in personal income tax rates.

To make an informed judgment about the different revenue options, the committee will need to evaluate the economic impact of the proposed Business Activity Tax, a value-added tax. We will provide analysis when LRO provides a model run of the VAT proposal.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – There are Better Ways to Raise Revenue in Oregon Than a Gross Receipts Tax

by r Hampton | Mar 6, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Taxing Transactions a Few Too Many Times

Yesterday, Representative Peter DeFazio (D-OR) and Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI) introduced the Wall Street Tax Act, which would create a financial transactions tax of 0.1 percent on stocks, bonds, and derivatives. The bill, which would “generate billions in revenue, while addressing economic inequality and reducing high risk and volatility in the market,” includes several cosponsors, including Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and 2020 presidential candidate Senator Kristen Gillibrand (D-NY). Policymakers should be wary about adopting a financial transactions tax.

Like a gross receipts tax, a financial transactions tax results in tax pyramiding. The same economic activity is taxed multiple times.

For example, an individual might sell a stock worth $100 to diversify her portfolio and then purchase stock in a new company with that same $100. The $100 is being taxed twice: first, when the individual sells the stock, and then again when the money is used to buy the new security. Imagine this happening thousands of times a day. The tax pyramiding quickly adds up. That is why this tax would generate nearly $770 billion over a decade.

Financial transactions taxes illustrate an important concept in tax policy. While economists, like me, argue that we want taxes that have low rates and broad bases, we should distrust taxes that have too low of a rate and too broad of a base. That generally means that the tax base is much too large and improperly structured.

Supporters, however, argue that the Wall Street Tax Act is needed, because it would reduce volatility in financial markets. It’s not clear that it would reduce volatility. In 2012, the Bank of Canada studied the issue and concluded that “little evidence is found to suggest that an FTT [financial transactions tax] would reduce speculative trading or volatility. In fact, several studies conclude that an FTT increases volatility and bid-ask spreads and decreases trading volume.”

The report also noted that there are “a number of challenges associated with the design and effectiveness of an FTT that could limit the revenues that FTTs are intended to raise. For these reasons, countries considering the imposition of FTTs should be aware of their negative consequences and the challenges involved in implementation.”

Sweden’s imposition of a financial transactions tax in the 1980s illustrates the challenges perfectly. The country experienced a 60 percent decrease in trading volume as it moved to other markets, as well as a decrease in revenue.

As policymakers debate new sources of revenue for the federal government, the financial transactions tax should not make the short list.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Taxing Transactions a Few Too Many Times

TAXTIMEKC

TAXTIMEKC