by r Hampton | Mar 5, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – The Top 1 Percent’s Tax Rates Over Time

As policymakers consider raising taxes on the richest Americans, it’s important to look at the top 1 percent’s tax burden from a historical perspective. Though the United States has had high marginal income tax rates in the past, the rich weren’t necessarily paying those rates. Understanding how the top 1 percent’s taxes have changed over time requires looking at not only the top marginal income tax rate but also effective rates and the share of income taxes paid, as well as the many expenditures that carve out the tax base.

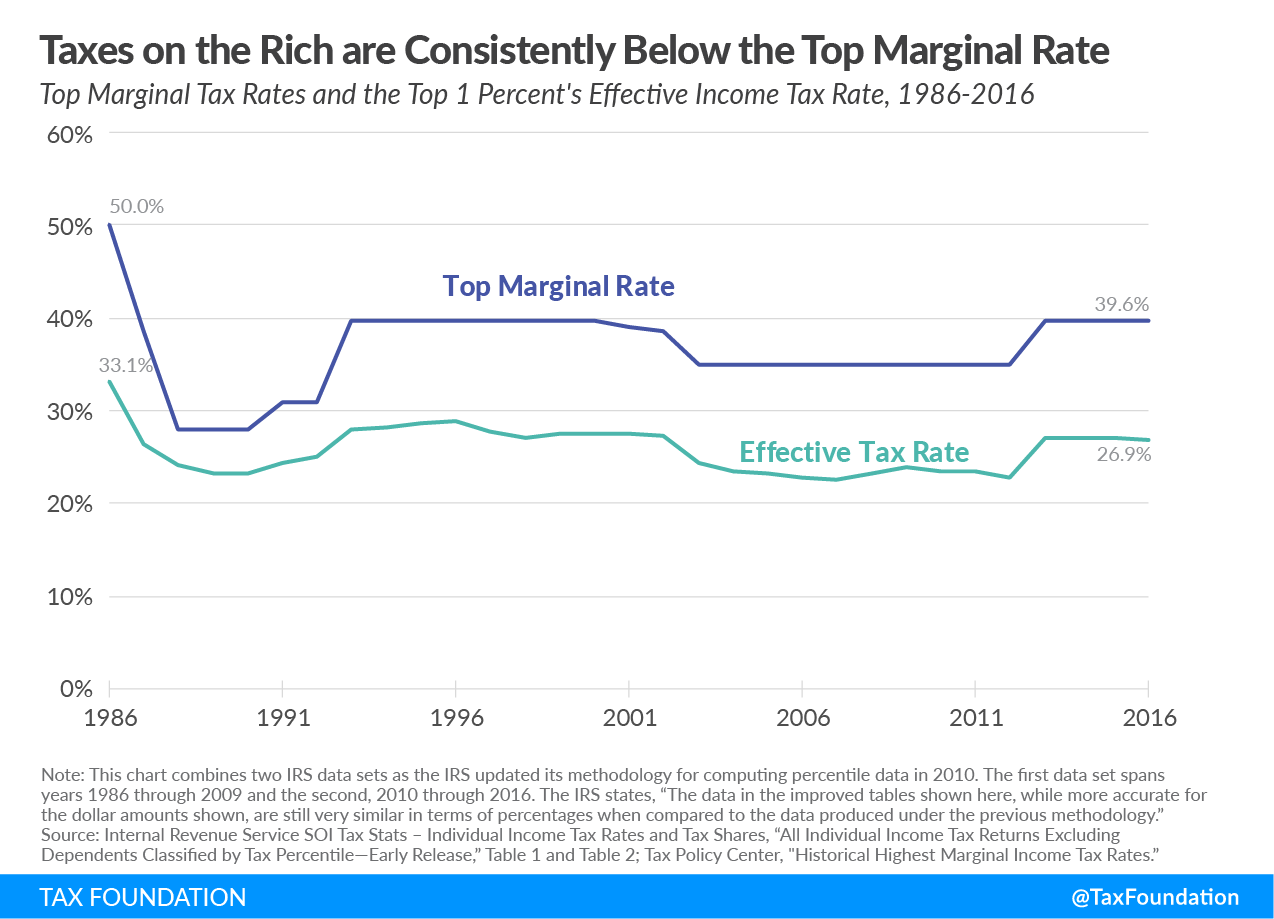

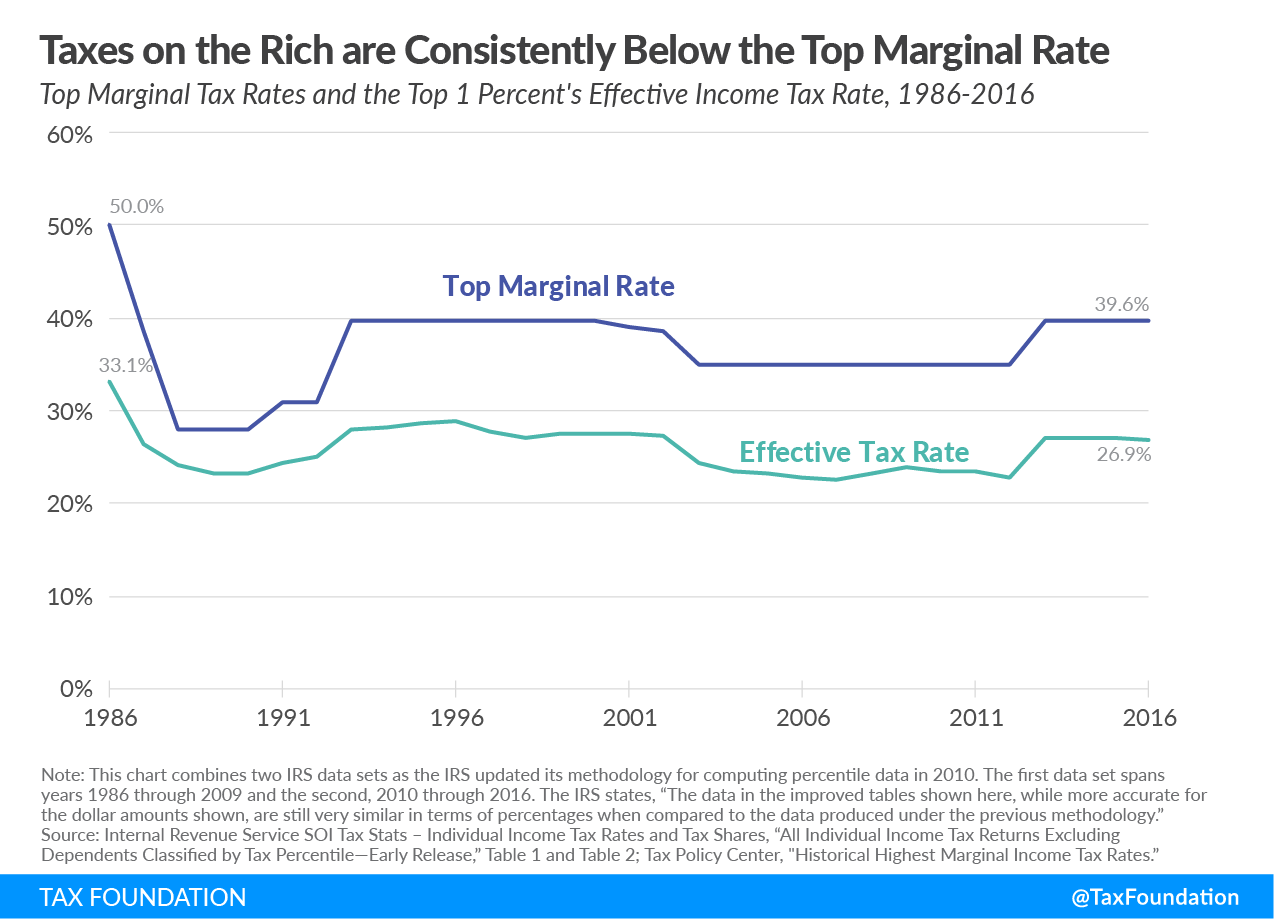

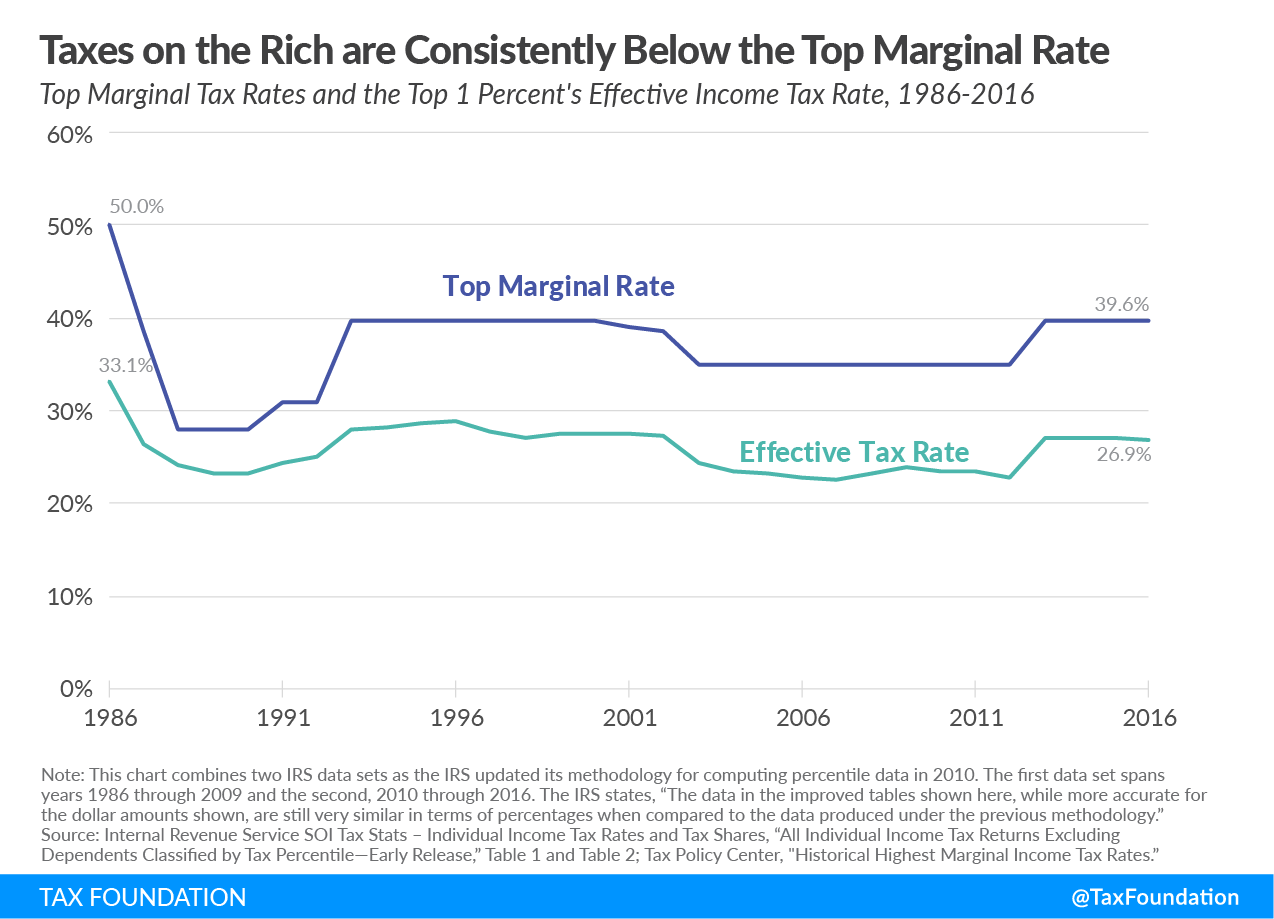

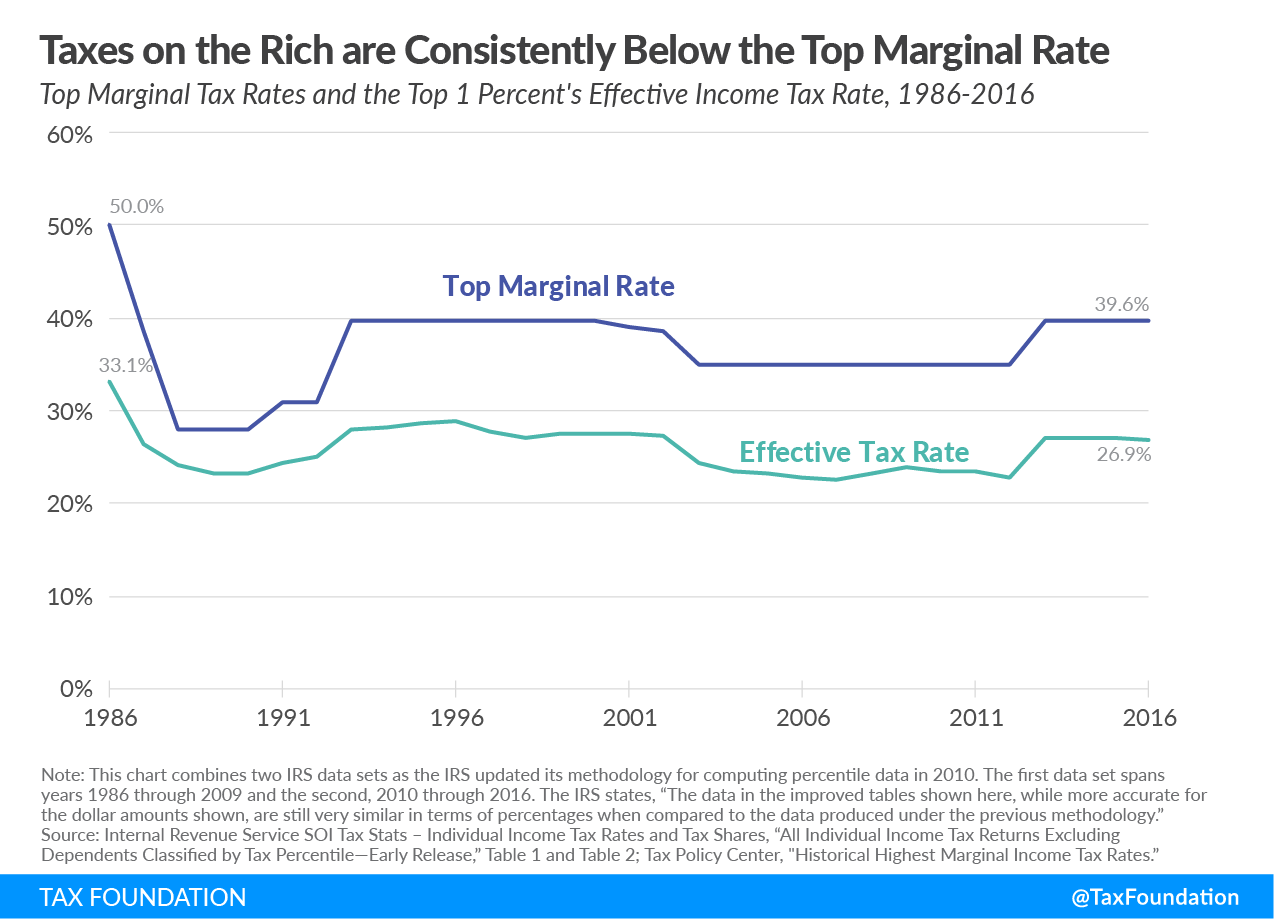

If we look at the top 1 percent’s effective tax rate (income tax liabilities divided by income), we see this story play out. The following chart shows the top marginal income tax rate and the top 1 percent’s effective tax rate.

The top 1 percent’s effective tax rate has consistently been below the top marginal income tax rate. Though this IRS data set only reaches back to 1986, another data set shows that the difference between these two tax rates used to be even greater. For example, in the 1950s, when the top marginal income tax rate reached 92 percent, the top 1 percent of taxpayers paid an effective rate of only 16.9 percent. Although the two data sets are not strictly comparable, they nevertheless show the consistency of the gap between the top marginal income tax rate and the effective rate.

Behind this difference was a plethora of tax expenditures that carved out the base. Economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez explain:

Within the 1960 version of the individual income tax, lower rates on realized capital gains, as well as deductions for interest payments and charitable contributions, reduced dramatically what otherwise looked like an extremely progressive tax schedule … The reduction in top marginal individual income tax rates has contributed only marginally to the decline of progressivity of the federal tax system, because with various deductions and exemptions, along with favored treatment for capital gains, the average tax rate paid by those with very high income levels has changed much less over time than the top marginal rates.

The tax code continues to be full of deductions, exemptions, and credits that shrink the tax base and bring the effective rate below the top marginal income tax rate. Even after accounting for such expenditures, however, the income tax system remains progressive.

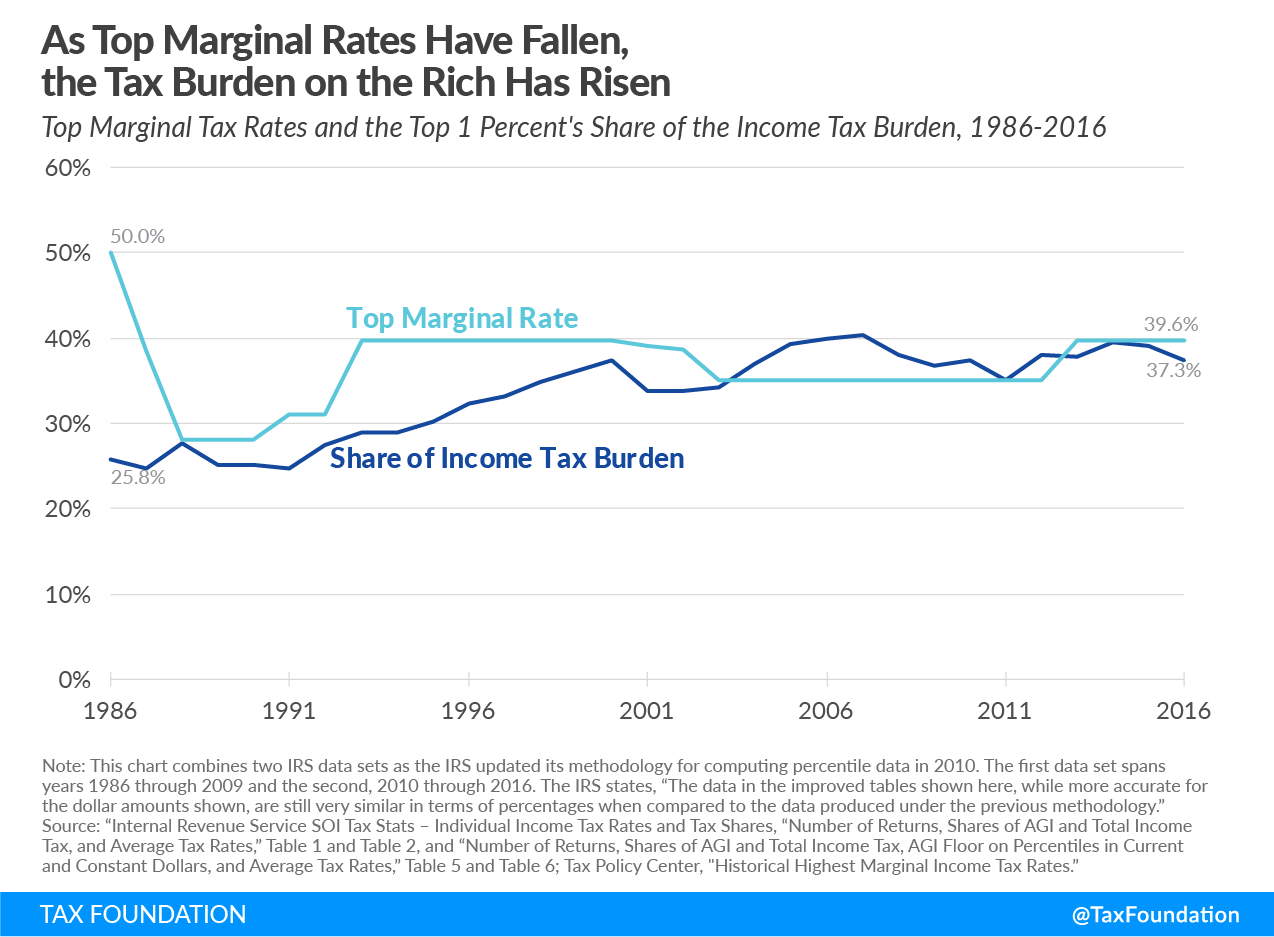

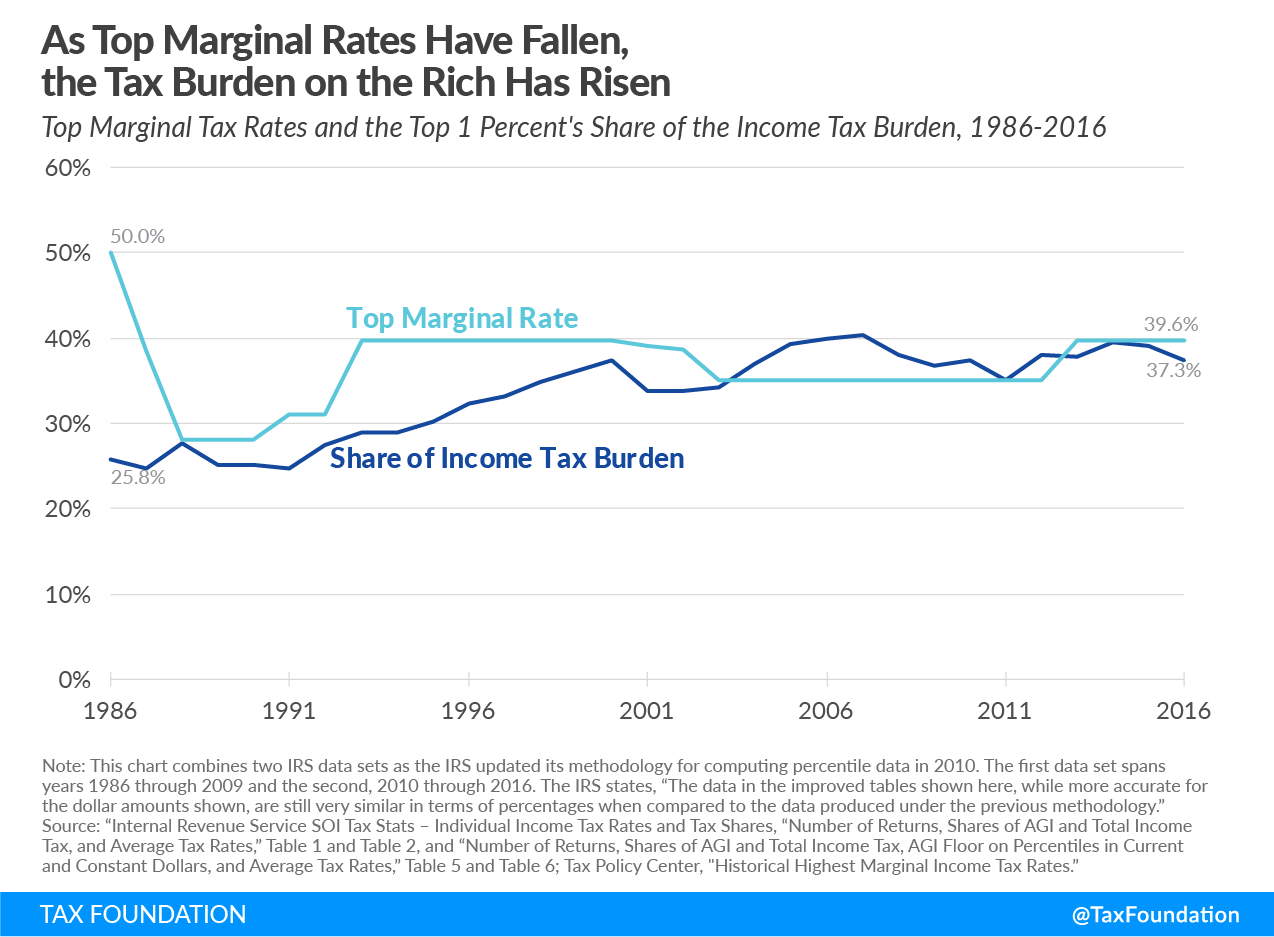

As this chart illustrates, higher marginal income tax rates didn’t necessarily result in a higher income tax burden for the wealthiest taxpayers. In fact, as the top marginal income tax rate has fallen, the top 1 percent’s income tax burden has increased. In 1986, the top marginal income tax rate was 50 percent, and the top 1 percent paid 25.8 percent of all income taxes; thirty years later, the top marginal income tax rate had fallen to 39.6 percent, but the top 1 percent’s share of income taxes had risen to 37.3 percent.

The growth of tax expenditures in recent decades has increased the percentage of nonpayers (taxpayers who owe zero income taxes after taking their deductions and exemptions), putting a greater share of the tax burden on those who continue to pay, meaning the top 1 percent now pays an increased share of the tax burden. The Tax Reform Act of 1986’s expansion of the standard deduction and the personal exemption, and more recently the creation and expansion of credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit, have increased the percentage of the population with a negative effective tax rate.

When looking at charts like these, one should be careful not to draw the wrong conclusions about whom the top 1 percent describes. Some might take the previous charts to show that this group includes the same people each year, but such a conclusion would be unfounded. These charts don’t tell us whether the top 1 percent contains the same people year after year, experiences a complete turnover annually, or something in between.

As it turns out, the composition of richest Americans has changed dramatically over time. As my colleague Erica York put it: “The wealthy aren’t a monolithic group of taxpayers. In fact, IRS data shows that there is typically a lot of churn within the group of top earners. For example, the number of taxpayers who report incomes of $1 million or more is highly variable and fluctuates with the business cycle.”

Looking at long-term trends can provide a valuable historical perspective to ongoing tax policy debates. As some policymakers call for raising the top marginal income tax rates, they should keep in mind that those rates and the top 1 percent’s tax burden don’t have a direct correlation. Policymakers would do well to remember that in some important respects, the taxation of the top 1 percent has not changed as much as they might think, and that marginal income tax rates are only part of the story.

Note: This is part of a blog series called “Putting a Face on America’s Tax Returns”

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – The Top 1 Percent’s Tax Rates Over Time

by r Hampton | Mar 4, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – Tax Foundation Response to OECD Public Consultation Document: Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digitalization of the Economy

Introduction

The Tax Foundation has engaged in tax policy debates since its founding in 1937. Our goal is to promote principles for sound tax policy and provide research and analysis that evaluate tax systems around the world. For us, the four important principles of sound tax policy are neutrality, simplicity, transparency, and stability. These principles, paired with an understanding of how tax policy affects long-term economic growth, create the basic framework the Tax Foundation uses to analyze tax policy.

This framework should be in the minds of all policymakers who are involved in the discussion of rewriting international tax rules. Ignoring these principles or the impact of taxes on growth could lead to more uncertainty for taxpayers, complexities that create barriers to cross-border trade and investment, new distortions throughout the global economy, and implications for global growth and prosperity. Beyond the political trade-offs of arranging a new system for allocating taxable profits or designing a global minimum tax, policymakers should pay attention to how the incentives of a new system will affect taxpayer behavior and incentives for investment.

Principles to Guide the Deliberations

As the Public Consultation Document expertly outlines, there are a variety of technical “solutions” to the challenges of digitalization. But any technical solution should be based on a set of principles grounded in sound economics. Solutions that ignore the economic consequences of the policy risk harming users, domestic businesses, global trade, and domestic economies. So how should the OECD think about these solutions?

Of the four principles articulated above, neutrality is arguably the most important because the lack of tax neutrality is what causes distortions and behavioral effects that can retard economic growth. The OECD must consider the neutrality question on multiple levels. For example, will the policy benefit large mature businesses over new or growing businesses? How will it impact businesses in different industries? Will the policy be neutral to small exporting countries and large market countries alike?

The OECD must also attempt to measure the potential compliance burden of any proposal it selects. Anecdotal evidence suggests that MNEs have already sustained substantial costs to comply with country-by-country reporting and the new BEPS rules. These were not one-time costs but are permanent deadweight costs to the companies and to the broader economy. It seems certain that each of the proposals under consideration would add a layer of complexity and compliance costs. Those costs should be evaluated in advance.

While the policy solution should minimize the compliance cost to taxpayers, economics teaches us that the true economic burden of taxes ultimately falls on consumers, workers, and capital. Therefore, the OECD should also attempt to estimate the economic effect of each of these proposals on users, workers, and the cost of capital before moving forward.

An ideal solution should also be neutral to country size. However, both the user participation proposal and the marketing intangibles proposal would tend to benefit countries with large markets. As a result, it is likely that these proposals would shift tax revenues away from small exporting countries and to large market countries. This raises the question of how the current debate will impact the tax sovereignty of smaller countries. The OECD should estimate the magnitude of any reallocation of tax revenues in advance.

Lastly, uncertainty has hung over international tax policy since the BEPS project was launched in 2012 and has likely been a contributing factor in the global slowdown in FDI and economic growth. Once the OECD resolves this current debate, it must work to have countries amend or repeal any unilateral or temporary measures that do not comply with the new approach. What taxpayers fear most is that countries will continue to enact unilateral measures even after the OECD settles on a global solution. The OECD should provide a process for evaluating these policies from an economic and legal perspective in order to build a foundation for a new, and potentially more stable, future for international tax policy.

Pillar 1 Approaches

A broad portion of economic activity across the globe is now driven by digital business models or business models that rely heavily on digitalization to reach new markets, serve their customers, and receive feedback on their products. Over time, that share of businesses that rely on digitalization or perform services via a digital platform will grow. Access to the internet allows individuals to use online services even if the providers of those services are not directly trying to reach those individuals.

As the OECD moves forward in determining how to reallocate some portion of taxable profits of multinationals, it will be important to maintain consistency between the method of allocation and the goal of reallocating. If the goal is to reallocate as much taxable revenue to a market jurisdiction as possible, then single sales factor apportionment of all profits (both routine and non-routine) would be the most effective although such a regime would likely cause many new distortions in both business and government behavior.

However, if countries are trying to strike a balance between maintaining the majority of the current international tax rules and only reallocate non-routine profits to different jurisdictions than where they currently get booked, a residual profit split method would be more appropriate. That approach would also have the benefits of its connection to current international tax rules and profit allocation methods as well as a focus on non-routine returns. Through this process, the OECD should work to design a system that will provide taxpayers clarity on where, why, and to what extent they will be taxed. A system that creates unnecessary surprises for tax liability in multiple jurisdictions would likely do more to harm growth than support cross-border trade and investment.

Fractional Apportionment

From an economic perspective, the least attractive option is the multi-factor fractional apportionment approach. This approach would likely raise the cost of capital around the world and result in shifting behavior by companies as they try to minimize the tax costs of their operations in markets where they would have new tax liability.

Fractional apportionment will create incentives not only for businesses responding to the factors and weights in the formula, but also for governments that may want to modify the formula for their own domestic benefit. The history of formulary apportionment among U.S. states reveals a drift toward single sales factor apportionment despite there being an initial agreement to allocate based on property, payroll, and sales. In 2018, just five U.S. states used three-factor apportionment while a majority used either single sales factor or overweight sales as a factor in their formulas.[1]

Allocating taxable profits to various jurisdictions based on sales or other factors also raises the question of whether a business would also be able to allocate loss carryforwards or carrybacks across jurisdictions. If that were the case, then the OECD should also seek agreement on which country’s rules or whether some set of international rules for restrictions on offsetting losses would apply. Otherwise, differing restrictions or limits on losses could cause further disputes over taxing rights.

User Participation Approach

The second least attractive option is the user participation approach. The OECD has already declared that the digital economy should not be ringfenced. Yet, the user participation approach seeks to do just that rather than find a solution that would be more neutral across industries. A user participation approach would create distortions as businesses seek to alter their business models to avoid the tax or minimize their exposure to this targeted policy.

Since the policy would allocate non-routine profits based on some metric of users, it clearly has the most potential of the three options to shift revenues from small exporting countries to populous market countries. The OECD should question the fairness of such a move. From an incidence perspective, however, if users are considered the value creators, then allocating taxes based on user participation is effectively a tax on them.

The user participation approach would also rely on analysis that would separate user-created value for non-routine profits from the value delivered by other company activities or assets. It would require a multitude of new simplifying assumptions that may result in economic value being misrepresented for users.

A shift to user-based allocation of taxing rights will also likely trigger behavior to undercount (or undervalue) users in some jurisdictions and overcount (or overvalue) them in other places.

Verifying user bases will likely prove difficult, especially if such an approach causes the users themselves to use tools that would mask their actual location. Allocation of taxing rights to a country that hosts VPN servers because users appear to be there would likely be a suboptimal outcome.

Moreover, this proposal seems to be based on the premise that users are geographically fixed. Digital companies cannot always track their customers. How is this proposal impacted by mobile customers?

For example, in 2017, some 39 million tourists visited the United Kingdom. Of these, the French topped all other tourist nationalities with nearly 4 million visits to the UK.[2] On the other hand, France is the most visited country in the world with 89 million visitors in 2017. According to one survey, France was the favorite destination for British tourists.[3]

The typical Briton visits 9.58 countries in their lifetime. Let’s say a British tourist visited Paris, Madrid, and Rome on the same trip and posted pictures of their visit to their favorite social media platform at every stop. How would this policy treat this tourist? Would they count as one “user,” or would they count as a different “user” in each country?

Customer mobility, thus, raises some practical questions for implementing such a user-based policy:

- Do countries that benefit more from tourism also benefit more from these proposals than other countries?

- Is there a mechanism for netting out tourists and business travelers between countries?

- Do tourists and business travelers count in their home country and not where they visit?

- Or, how does the digital platform company know where their user is from?

A related point is that contributions by various users may seem similar (pictures or short videos) but may be much more valuable if the contribution is from a particular user with broad popularity among other users. The allocation of profits based on user contributions would then need to include other difficult steps of analysis. The initial contribution could be more valuable depending on who is making the contribution, and that is partially determined by the number of other users who pay attention to the user making the contribution, and the number of users who are interacting with the contribution.

A single post on a social media platform by a famous personality—President Trump, Ruben Gundersen, or PewDiePie, for example—could drive interactions from users all over the globe. If all the value associated with that post is allocated to the user who posted it, then the value associated with shares, likes, and views is ignored.

For example, the OECD’s Tweets are seen by thousands of interested parties across the globe. No doubt, these Tweets drive countless users to visit the OECD’s website located in Paris. If the OECD’s website was considered an interactive social media platform, the question would be whether those “hits” would be allocated to France or the source country of the person who posted their content.

So, while the aim of the policy is to make large digital firms pay “their fair share” of taxes, the party most harmed by the policy would be, for example, a small ceramics maker in Spain who is trying to reach a larger market, or the small hotel owner in Tuscany who is trying to attract Nordic vacationers.

Many social media platforms track metrics like revenue per user. Some modified version of this metric could be used to simplify the analysis. However, any formulaic approach should be tailored to account for differences across business models even within the three main lines of business targeted by this approach.

Marketing Intangibles

Of the three options, the marketing intangibles approach would seem to produce the least amount of economic harm for the activities of current, mature multinationals. For these existing multinationals, this option would likely add the least amount of extra compliance burden—although not zero—because it is based on established procedures in the current transfer pricing system.

The OECD should measure how a rules change under this approach might impact growing businesses that aspire to reach customers around the globe. Putting a safe harbor in place to protect small and medium-sized enterprises from the changes may seem like a helpful approach for smaller firms. However, a sufficiently complex policy with a safe harbor for smaller firms might make it more likely for a growing firm to get bought out rather than achieve success as a separate global firm.

In general, allocating taxing rights for non-routine profits based on a company’s investment in marketing intangibles could lead to businesses changing their marketing strategies and ultimately having less efficient or more expensive models for acquiring new customers. A likely consequence of shifting taxing rights to large market countries is that these tax costs would simply be shifted forward to domestic advertisers or sales operations.

Like the User Participation approach, the Marketing Intangibles approach would also tend to favor large market countries, likely shifting profits and revenues away from small exporting countries. Again, the OECD should measure these tax base effects before moving forward.

Pairing an apportionment regime with a withholding tax to ease the administration costs for smaller countries could create compliance burdens for businesses and barriers to cross-border investment. Therefore, countries permitted to administer withholding taxes under any of the allocation approaches should pay attention to whether their compliance regimes or processing of tax returns from multinational businesses work as barriers to trade by harming the ability of companies to have tax certainty for their operations in the jurisdiction.

Focus on Noncompliant Policies

Beyond seeking agreement on some new allocation method, the OECD should commit to reviewing policies that countries have used to unilaterally expand their tax bases and evaluate whether they fit with the new international system that will result from this process. The OECD should begin an effort now to focus on the economic, administrative, and legal consequences of these unilateral policies so that there may be broad understanding of how each fits (or perhaps does not fit) within the eventual agreed-upon system.

In recent years, various countries have sought to expand their tax base through unilateral efforts. Among other policies, these efforts include diverted profits taxes, digital services taxes, and definitions for digital permanent establishments. Some of these measures are specifically designed to tax digital companies or certain multinational business models differently than other businesses are taxed. This diverse set of policies and the political momentum behind them could undermine the current OECD process or the stability of whatever agreement is eventually reached.

The potential ramifications of both the eventual agreement and the unilateral measures should be fully analyzed before the current OECD process concludes.

It would be quite unfortunate, and perhaps even a failure of the OECD process, if an international agreement was reached, but individual countries still felt it necessary to continue to administer unilateral policies that go against that agreement.

The BEPS project has resulted in a sort of floor for tax competition for policy regimes previously designed to attract investment or taxable profits from multinational corporations. A ceiling may now be necessary to limit base expansion efforts by taxing jurisdictions. The current, slow shift from source-based to destination-based taxation can be seen in the proposals being considered by the OECD and in many unilateral efforts. However, this shift is currently uncoordinated and creating more complexity than certainty for taxpayers. The OECD must then succeed in reaching agreement on a system that allows this shift of taxing rights to market jurisdictions to continue while minimizing chaos and quickly resolving issues of double taxation.

It is therefore critical for the OECD to take a clear stance that it will undertake a review of unilateral policies of base expansion to set the stage for elimination of those policies that could undermine the current process and eventual agreement. Analysis should focus on the economic impact of policies, the complexities they create, distortions to economic activity, and whether they present barriers to entry to companies looking to expand their market footprint. Additionally, the OECD should review policies from the stance of a government evaluating the revenue generation of policies, the auditing process, and the overall costs of administering the policy. Finally, the OECD should contribute legal analysis that would allow for future comparison of policies in the context of a new international agreement, including how unilateral policies align with existing or revised treaty obligations and how they create or undermine certainty for taxpayers.

Pillar 2 Policies

OECD research[4] has found that the corporate income tax is the most harmful for economic growth, and research by IMF staff[5] has found that transfer pricing regulations like those associated with the BEPS project effectively work as an increase in corporate tax rates. This directly impacts the cost of capital, decisions on whether to invest or expand in a particular jurisdiction, and long-run economic growth.

Tax competition has lowered the cost of capital and barriers to trade and investment across the globe. Placing a floor on tax competition or raising taxes on non-routine profits from intangible assets could have serious economic effects.

A minimum tax targeted at non-routine profits would directly lower the after-tax return on investment in business lines that generate high returns. This approach also calls into question how such a policy might impact the sovereign choices of tax jurisdictions. Though the consultation document is silent on the rate of taxation, it is important for the OECD to avoid several potential pitfalls of a minimum tax approach.

First, FDI should be excluded from the tax base of any minimum tax. As the OECD’s own work has concluded, inbound FDI is incredibly sensitive to tax rates.[6] A global minimum tax regime that creates a tax burden on FDI will create distortions that lead to more investment decisions based on tax rather than market reasons. Instead of effects that individual countries might see in FDI shifting elsewhere, a global regime could reduce FDI everywhere.

At a time when FDI has been falling and global trade negotiations are tenuous, it is particularly important for the OECD to study how various minimum tax regimes might interact with FDI flows.[7]

Second, the minimum tax should be assessed on a net basis. A gross-based minimum tax triggered by a formula or threshold would likely give rise to high effective tax rates for firms that operate on thin margins while more profitable firms would see lower effective rates. Just like the digital services tax (DST) proposals would create distortions by applying a tax to revenues rather than profits, a minimum tax regime that is based off revenues would make those distortions go worldwide.

The average U.S. firm has a profit margin of just under 9 percent.[8] As a simple example, a firm with $100 in sales and $90 of costs would have a 10 percent profit margin. If that firm faces a 25 percent corporate tax rate, it would pay $2.50 in taxes on its profits. A gross-based tax of just 2.5 percent would raise the same revenue. However, because the gross tax does not account for costs, it will impact unprofitable firms while a net income tax would not. This is particularly relevant because several DST proposals have called for rates greater than 2 percent.

Third, a minimum tax regime should, like the intent behind the U.S. GILTI (as the consultation document describes), aim to tax non-routine profits. There must also be attention paid to what counts as routine profits and non-routine profits on a country-by-country basis. This could be done by allowing a deduction for a percentage of business investment in a jurisdiction; however, the definition of what can be contained in the deduction will need to be carefully crafted to minimize complexity and contradictions with various existing domestic tax regimes. A cap on the deduction could be tailored to local rates of return.

Fourth, the minimum tax (targeted at super-normal returns) should have few triggers. A regime that includes an exemption for small and medium enterprises could do more harm to those businesses over the long run than good. Similar to the impact of a safe harbor paired with a Pillar 1 policy, a sufficiently complex minimum tax that has an exemption threshold with the goal of protecting small and medium enterprises could make it more likely that those businesses would be bought out by a larger global firm rather than grow to pass the threshold and learn to comply with the law on their own.

Finally, the minimum tax regime should be as simple as possible for both compliance and administration. This will likely be the largest challenge of all, but it could be the key to making the eventual compromise more stable over time and to making the new system less burdensome than the current one from a complexity standpoint.

Conclusion

The current state of international political and economic affairs is fragile. There are threats to sustainable growth and challenges to trade relationships from China, to the UK, and the United States. International tax policy is having a similarly uncertain moment with individual countries seeking to expand their taxing rights in a unilateral fashion—making double taxation scenarios more likely for multinational businesses.

Though the challenges to international tax policy are many, the OECD has a chance to work toward a system that creates fewer distortions and negative economic effects than the current one. However, given the policies on the table, it will certainly take quite an effort to avoid further complexity of international tax rules that creates challenges to global trade and economic prosperity.

[1] Taxadmin.org, “State Apportionment of Corporate Income,” Jan. 1, 2019, https://www.taxadmin.org/assets/docs/Research/Rates/apport.pdf.

[2] VisitBritain.org, “Market Ranks and Growth 2003-2017,” https://www.visitbritain.org/sites/default/files/vb-corporate/Documents-Library/documents/2017_ranks_and_growth_65_markets_for_web.xlsx.

[3] Kara Godfrey, “Mapped: How many countries have Britons travelled? The number is surprising,” express.co.uk, March 16, 2018, https://www.express.co.uk/travel/articles/932706/how-many-countries-britons-travel-favourite-holiday-destinations.

[4] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Tax and Economic Growth,” Economics Department Working Paper No. 620, July 11, 2008, http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?doclanguage=en&cote=eco/wkp(2008)28

[5] Ruud A. de Mooij and Li Liu, “At A Cost: the Real Effects of Transfer Pricing Regulations,” International Monetary Fund, March 23, 2018, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/03/23/At-A-Cost-the-Real-Effects-of-Transfer-Pricing-Regulations-45734.

[6] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Tax Effects on Foreign Direct Investment: Recent Evidence and Policy Analysis,” OECD Tax Policy Studies No. 17, Dec. 20, 2007, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/tax-effects-on-foreign-direct-investment_9789264038387-en#page1.

[7] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “World Investment Report 2018,” https://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=2130.

[8] Aswath Damodaran, “Margins by Sector (US),” stern.nyu/edu, January 2019, http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/margin.html.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Tax Foundation Response to OECD Public Consultation Document: Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digitalization of the Economy

by r Hampton | Mar 1, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – What Happens When Everyone is GILTI?

This week, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin endorsed the idea of a global minimum tax following meetings with French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire in Paris.

Secretary Mnuchin was quoted as saying, “We think it’s very important, the concept of minimum taxes, and that there isn’t a chase to the bottom on taxation.” These comments are in the context of an ongoing global discussion about changing international tax rules with an eye towards the digitalization of the economy.

In February, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released a Public Consultation Document that outlined several policy options for allocating tax revenues and establishing a minimum tax on certain profits of multinationals. The OECD document specifically refers to the new U.S. policy of Global Intangible Low Tax Income (GILTI). Secretary Mnuchin also referred to this policy in his remarks in Paris.

GILTI acts as a minimum tax on earnings that exceed a 10 percent return on a company’s invested foreign assets. GILTI is subject to a worldwide minimum tax of between 10.5 and 13.125 percent on an annual basis. Some U.S. multinationals may, however, face rates on GILTI higher than 13.125 percent.

At the OECD, the interest is in taking the U.S. model for minimum taxation and making it go worldwide. So, where a French company might pay a very low rate of tax on their foreign operations in Ireland, a GILTI regime could increase the tax rate on those foreign profits.

The OECD document is silent on what rate would be used for the global minimum tax, but it is likely that it would ultimately increase tax rates on profits earned in low-tax jurisdictions.

From a broad standpoint, the minimum tax would set a floor for tax competition and could undermine the sovereignty of some taxing jurisdictions. Ireland has a corporate tax rate of 12.5 percent and Hungary has a rate of just 9 percent. If the minimum tax has a rate higher than those countries, then some of their competitive advantage on tax policy would be wiped out.

A global minimum tax also comes with several potential pitfalls. As I recently pointed out, there are three key issues that policymakers need to pay attention to when designing a minimum tax:

- Use this opportunity to eliminate harmful, unilateral digital taxes

- Exempt Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) from the tax base

- Make the system simple for compliance

A minimum tax could mean the end of tax competition on corporate tax rates. However, countries should continue to work to improve their corporate tax base and other areas of their tax systems.

OECD research has found that the corporate income tax is the most harmful for economic growth. A global minimum tax would directly impact the cost of capital, decisions on whether to invest or expand in a particular jurisdiction, and long-run economic growth.

Tax competition has lowered the cost of capital and barriers to trade and investment across the globe. Placing a floor on tax competition or increasing tax rates on profits from multinational businesses could have serious economic effects.

Secretary Mnuchin, Finance Minister Le Maire, and other tax policy leaders should encourage the OECD and their own research staff to perform serious economic analysis on the alternatives for changing international tax rules before moving forward. It would be quite unfortunate for the world to learn the wrong lessons from U.S. tax reform.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – What Happens When Everyone is GILTI?

by r Hampton | Mar 1, 2019 | Tax News

Tax Policy – To Remedy Tax Compliance Problems, Gig Economy Firms Need Policy Certainty

Earlier this month, the Department of the Treasury’s Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) released a report on tax compliance for gig economy workers. The report examined whether workers in the gig economy—including those working on sharing economy platforms—are remitting their self-employment tax liabilities accurately.

TIGTA found that 13 percent of gig economy workers with gig economy income above $400 failed to report the income for self-employment and income tax purposes in 2016. As TIGTA points out, the compliance problem may stem from uncertainty around reporting requirements for gig economy firms. This problem shows how statutes in the tax code must be updated to accommodate new economy work.

Unlike traditional employment arrangements, participants in the gig economy are considered independent contractors. Independent contractors are responsible for tracking, reporting, and remitting their tax liabilities, as the firms they are contracted with have no obligation to withhold taxes from their paychecks. In addition to personal income tax, contractors must also pay self-employment tax of 15.3 percent on their first $132,900 of individual income, the Medicare part of the self-employment tax of 2.9 percent on individual income over $132,900, and the additional Medicare tax of 0.9 percent on income above $200,000 when filing single, which mirrors an employee’s payroll tax liability.

Gig economy workers may not be accustomed to withholding their own taxes, as many gig economy workers use it to supplement income from a full-time job. These workers may rely upon data furnished by gig economy firms to determine their tax liabilities, such as information from Form 1099-K. Form 1099-K provides a summary of income earned through an independent contract to the taxpayer and to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

However, gig economy firms do not provide Form 1099-K to all contractors, as Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §1050-W does not require third-party settlement organizations (TPSOs)—organizations that make payments to merchants via a third-party payment network—to do so until a de minimis threshold of $20,000 and 200 transactions is reached by the contractor. Contractors under the threshold may lack an important source of information when preparing their tax returns, and the IRS has less information to reference when identifying mistakes or finding tax evasion.

Originally, this provision was meant to provide a de minims threshold for firms facilitating payments between buyers and sellers, such as online auctions and firms mediating financial transactions. The provision was not intended for gig economy firms, as it was enacted prior to their emergence. There has been no formal guidance from the IRS to clarify for gig economy firms whether they should be defined as TPSOs, and the Treasury Department argues that “the information reporting gaps created by the emergence of the gig economy may require regulatory or legislative action.” As of now, gig economy firms must rely on their own judgment or IRS Private Letter Rulings in specific cases to determine if they are considered a TPSO and qualify for the de minimis threshold.

A proposal to lower the de minimis threshold for reporting should balance the information needs of workers and the IRS with the added administrative costs placed upon gig economy firms. There is evidence that Form 1099-K issuance has only a limited impact on tax compliance, as it does not track taxpayer expenses or tax basis for property sold via a gig economy platform. Additional Form 1099-Ks may help the IRS identify noncompliance or mistakes more quickly, heading off the chance that workers make the same errors in their self-employment taxes over several tax seasons. At the minimum, the IRS and the Treasury Department should clarify whether gig economy firms meet the definition of a TPSO. Policymakers might also reconsider the de minimis thresholds for these types of businesses.

The lack of clarity on Form 1099-K reporting requirements for gig work shows how existing statutes need to be updated to properly tax new economy firms. Establishing policy certainty should be a top objective for policymakers as new economy work is incorporated into the tax code.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – To Remedy Tax Compliance Problems, Gig Economy Firms Need Policy Certainty

TAXTIMEKC

TAXTIMEKC